Genetics is messy. Seriously. You probably remember Gregor Mendel and those pea plants from high school biology, right? It all seemed so simple when we were just looking at whether a pea was purple or white. But life isn't usually just one single trait. Things get weirdly complicated once you start looking at punnett square two traits problems—what scientists actually call dihybrid crosses. Honestly, trying to track two different things at once, like hair color and eye color, or a plant’s height and its seed shape, feels less like science and more like trying to do Sudoku while someone yells numbers at you.

It’s about probability. Pure and simple.

💡 You might also like: Nan Thai Fine Dining Spring Street Northwest Atlanta GA: Why It Still Dominates the City

Most people mess this up because they forget that genes usually sort themselves out independently. This is Mendel’s Law of Independent Assortment. If you’re tracking a dog’s fur length and its ear shape, the gene for fur doesn’t care what the gene for ears is doing. They’re doing their own thing. Usually. Unless they’re "linked," but let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

The Math Behind a Punnett Square Two Traits Grid

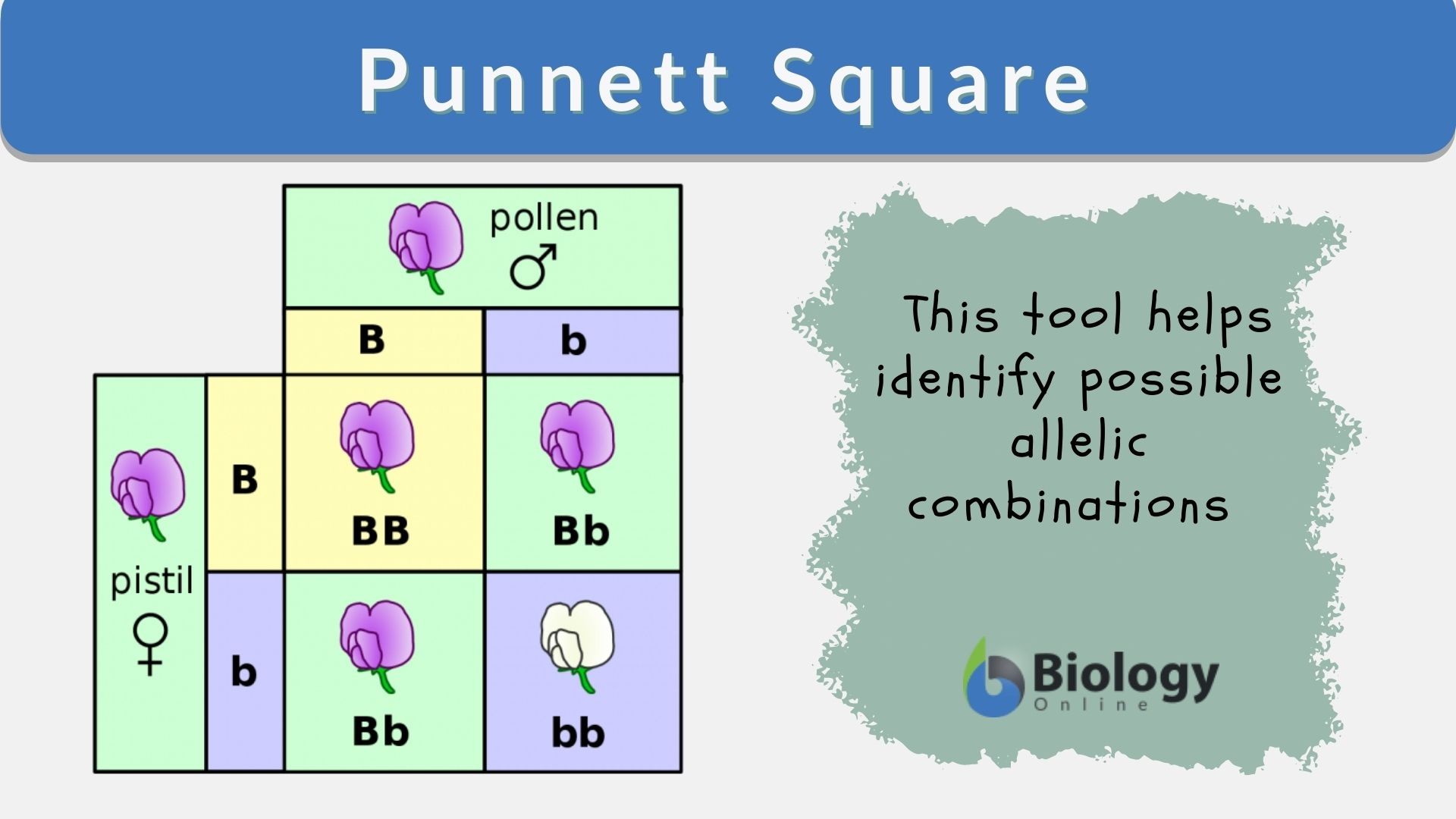

When you move from one trait to two, the grid doesn't just double. It quadruples. A standard single-trait square has four boxes. A punnett square two traits grid has sixteen.

Why sixteen? Because each parent can produce four different combinations of alleles in their gametes (sperm or egg). If you have a parent with the genotype $AaBb$, they don't just pass on $Ab$ or $aB$. They can give $AB$, $Ab$, $aB$, or $ab$. You have to account for every single one of those possibilities on both sides of the square.

Imagine you're breeding "imaginary" dragons. Let's say Green scales ($G$) are dominant over blue scales ($g$), and Fire-breathing ($F$) is dominant over frost-breathing ($f$). If you cross two dragons that are both heterozygous for both traits ($GgFf \times GgFf$), you’re looking at a massive 16-box nightmare.

Most students start strong and then lose their place halfway through. They’ll put $GG$ in a box but forget the $F$s. Or they’ll accidentally write $Gg$ when it should be $GG$. It’s tedious. You have to be meticulous.

The Famous 9:3:3:1 Ratio

If you’re doing a punnett square two traits cross where both parents are heterozygous (meaning they carry one dominant and one recessive version of both genes), you will almost always see a specific pattern in the physical results. This is the 9:3:3:1 phenotypic ratio.

Out of 16 offspring:

- 9 will show both dominant traits (Green scales, Fire-breathing).

- 3 will show the first dominant but the second recessive (Green scales, Frost-breathing).

- 3 will show the first recessive but the second dominant (Blue scales, Fire-breathing).

- 1 lonely individual will show both recessive traits (Blue scales, Frost-breathing).

This ratio is the gold standard of classical genetics. If you see these numbers in a real-world experiment, you know you’re dealing with two independent genes. But here’s the kicker: nature loves to break rules.

Where Reality Breaks the Square

We talk about these squares like they’re absolute truth. They aren't. They’re models. And models have limitations.

One major snag is Gene Linkage. Thomas Hunt Morgan discovered this while looking at fruit flies at Columbia University back in the early 1900s. He noticed that some traits, like wing shape and body color, seemed to "stick together" way more often than the 9:3:3:1 ratio predicted. This happens because those genes are physically located close to each other on the same chromosome. They’re like neighbors on a bus; they usually get off at the same stop. If genes are linked, your 16-box square will give you totally wrong predictions.

Then there’s Epistasis. This is when one gene hides or masks the effect of another gene. Think about Labrador Retrievers. One gene determines if they are Black or Brown. But another gene determines if that color actually shows up in their fur at all. If the second gene says "no color," you get a Yellow Lab, regardless of whether the first gene said "Black" or "Brown."

If you try to map a Yellow Lab's lineage using a basic punnett square two traits approach without knowing about epistasis, you'll be scratching your head for hours.

Setting Up Your Square Without Losing Your Mind

If you're staring at a homework assignment or trying to figure out what your future kids might look like (don't, it's more complex than this), you need a system. Use the FOIL method. You might remember this from algebra: First, Outer, Inner, Last.

Let's use a real example. Pea plants.

Round seeds ($R$) are dominant to wrinkled ($r$).

Yellow seeds ($Y$) are dominant to green ($y$).

If your parent plant is $RrYy$:

- First: $R$ and $Y$ (Gamete: $RY$)

- Outer: $R$ and $y$ (Gamete: $Ry$)

- Inner: $r$ and $Y$ (Gamete: $rY$)

- Last: $r$ and $y$ (Gamete: $ry$)

Those four combinations go across the top. Do it again for the other parent along the side. Now, fill in the boxes. Always keep the same letters together ($R$s with $R$s) and always put the capital letter first. It keeps things readable. Writing $rR$ is technically fine, but it makes it way harder to spot the patterns later.

The Mystery of Lethal Alleles

Sometimes, the squares don't work because some combinations simply don't survive. In certain species, having two dominant alleles for a specific trait is fatal. This is called a "lethal allele."

For example, in Manx cats, the gene for being tailless is dominant ($T$). But if a kitten inherits two dominant $T$ alleles ($TT$), it usually dies before birth because the spinal cord doesn't develop correctly. If you did a punnett square two traits for a Manx cat and another trait, your 16-box results would be missing certain individuals. You’d be looking for a 1/16th chance that literally doesn't exist in the living population.

Why This Actually Matters Today

You might think this is just academic fluff. It’s not.

In agriculture, this is how we get crops that are both drought-resistant and high-yield. Plant breeders spend their lives looking at these crosses. In medicine, understanding how two traits interact is vital for "polygenic" conditions—illnesses caused by multiple genes working together. While a simple square can't map out something as complex as heart disease, it's the foundation for understanding how those genetic components stack up.

Even in 2026, with all our CRISPR technology and advanced gene sequencing, we still go back to these basic probabilities. It’s the logic of life.

Actionable Steps for Mastering Dihybrid Crosses

If you want to get these right every time, you have to stop rushing. Speed is the enemy of genetic accuracy.

- Double-check your gametes. If you mess up the FOIL step, the entire 16-box grid will be garbage. Take thirty seconds to ensure you have four unique combinations.

- Use colors. Seriously. Use a blue highlighter for one trait and a yellow one for the other. It helps your brain separate the $B$s from the $D$s when things get crowded.

- Verify the phenotypes. Once the square is filled, don't just count. Mark them. Put a little "x" for every individual that shows both dominant traits. Then use a different symbol for the next category.

- Look for the "Double Recessive." The bottom-right box should usually be your $aabb$ individual. If it’s not, you probably misaligned your rows and columns.

- Check for Linkage. If you’re looking at real data and the numbers are nowhere near 9:3:3:1 (and your sample size is big enough), stop trying to force the square to work. The genes are probably linked or epistatic.

Mastering the punnett square two traits is basically just a test of your organization skills. It’s not that the math is hard—it’s just addition—but keeping the variables straight requires a level of focus that most people overlook. Once you see the pattern, you can't unsee it.

Insights and Practical Applications

The most important takeaway is that genetics is a game of chance. A Punnett square tells you the probability, not the certainty. If a square says there is a 25% chance of a specific trait appearing, that doesn't mean if you have four offspring, one must have it. It means every single individual has a 25% chance. You could have ten offspring and none show the trait, or all ten could show it.

To truly understand how traits move through generations, you have to look at large populations. This is why Mendel used thousands of pea plants. Small samples lead to skewed data. When applying this to your own life—whether it's breeding pets or understanding your own family history—always remember that the square is a map, but the territory is much more complex.

Focus on the mechanics of the $4 \times 4$ grid first. Once you can fill that out without a single error, you've mastered the logic that underpins almost all of modern inheritance theory.