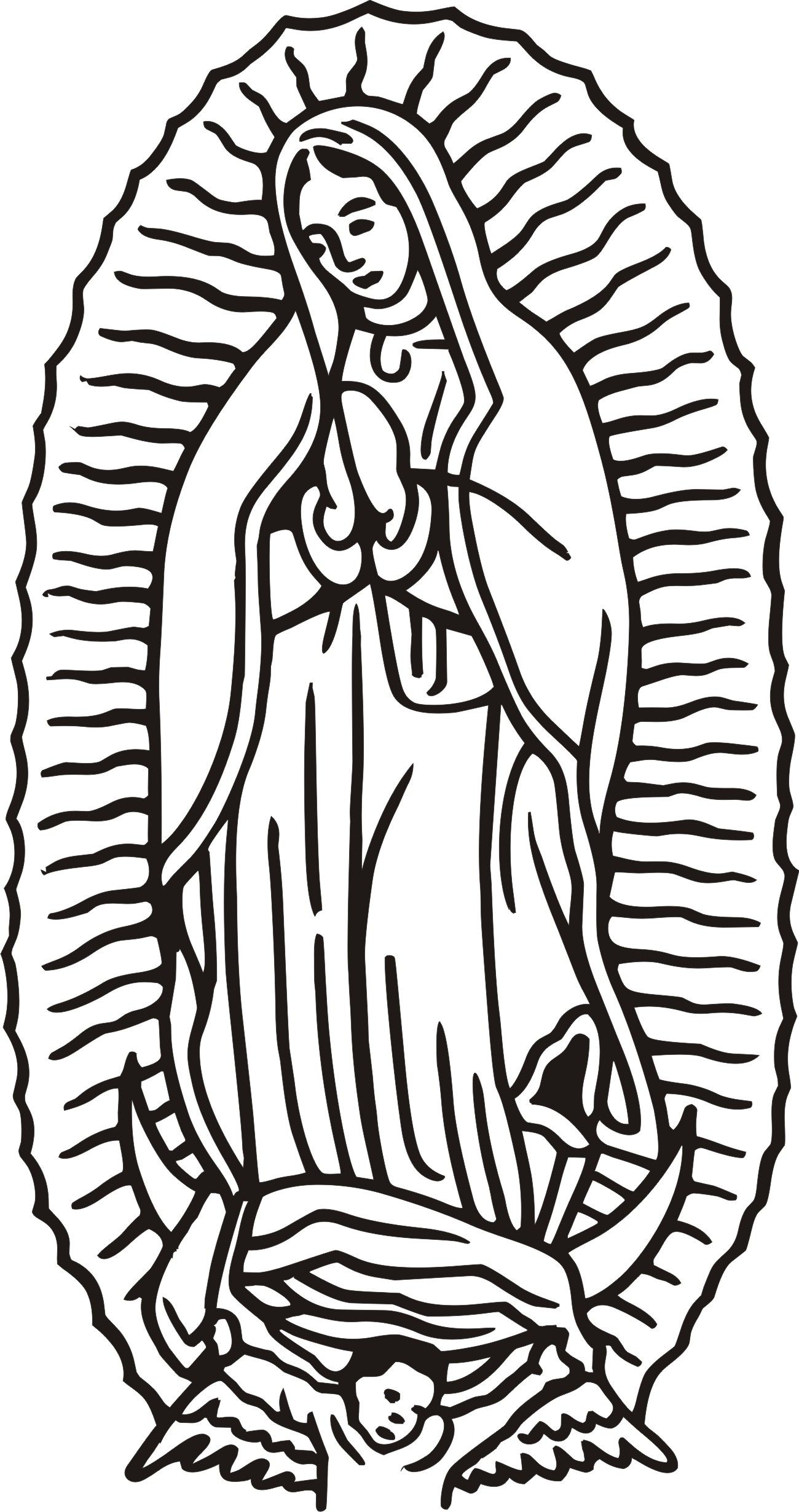

It is easily the most reproduced image in the Western Hemisphere. You see it on car windows, prayed over in massive cathedrals, stitched into denim jackets, and tattooed across countless shoulders. But drawing La Virgen de Guadalupe isn’t just about sketching a woman in a cloak; it’s about navigating a visual language that has remained largely unchanged since 1531. Honestly, if you mess up the tilt of the head or the specific shade of the turquoise mantle, you aren't just making a "stylistic choice." You're actually missing the entire point of the iconography.

People get intimidated. They see the gold rays and the intricate flowers and they freeze up. Don't. It is basically a series of geometric symbols layered over a human form.

Most artists start with the face, which is a mistake. If you want to get this right, you have to start with the posture. The original image on the tilma (the cloak of Saint Juan Diego) isn't standing straight. She's leaning. It’s a slight, graceful shift of weight—a contrapposto—that gives the figure its life.

The Secret Geometry Behind Drawing La Virgen de Guadalupe

There is this specific vibe to the original image that modern digital recreations often lose. It feels "heavy" yet floating. When you begin drawing La Virgen de Guadalupe, you’re dealing with a very specific set of proportions. Her head tilts to the right. Her eyes are cast downward. This isn't just "sadness." In the context of the 16th century, this was a massive cultural signal of humility and compassion.

The mantle is where most people quit. It’s a deep, blue-green—specifically a turquoise that represented royalty to the Aztec people. If you use a standard royal blue, it looks like a generic European Madonna. It’s wrong. It needs that hint of sea-foam or teal.

And then there are the stars.

👉 See also: Ice Breakers Cinnamon Gum: What Most People Get Wrong About That Spicy Kick

The stars on the mantle are not random. Astronomers like Dr. Juan Homero Hernández Illescas have actually mapped these points. They supposedly correspond to the constellations visible over Mexico City during the winter solstice of 1531. If you're just doodling dots, you're missing the "map" aspect of the piece. When you are drawing La Virgen de Guadalupe, try to group the stars into clusters rather than a uniform polka-dot pattern. It adds a layer of authenticity that experts will notice immediately.

Why the Hands are the Hardest Part

Look closely at the original. The hands are joined in prayer, sure. But look at the skin tone. One hand is slightly lighter, and the other is slightly darker. This was a deliberate "mestizo" representation—the blending of European and Indigenous races.

If you draw both hands with the exact same Copic marker or digital hex code, you lose the "Encounter" (El Encuentro) that the image is supposed to represent. Also, the fingers. They are long and tapered. Don't make them stubby. They should look like they are barely touching, creating a sense of internal peace.

The Mandorla: More Than Just "Gold Spikes"

The sunburst behind her is called a mandorla. It's basically a full-body halo. But here is the trick: the rays aren't all the same. Some are straight, like spears of light, while others are wavy, like flickering flames. This represents the sun, specifically the sun deity Huitzilopochtli, being eclipsed by something greater.

- The Straight Rays: Use a ruler for these. They provide the structure.

- The Wavy Rays: These need to be hand-drawn. They provide the "heat" and movement.

- The Black Moon: She stands on a crescent moon. It’s dark. It signifies that she is standing over the "night," or the old era.

If you paint the moon white or silver, you're following European tradition, not the Guadalupe tradition. Keep it dark gray or black. It grounds the entire composition.

👉 See also: Why Off Grid Misty Nudes Are Dominating the Modern Photography Aesthetic

Dealing with the Angel at the Bottom

The angel holding the bottom of the robe is often the most "cartoonish" part of amateur drawings. Big mistake. The angel in the original doesn't look like a chubby Renaissance cherub. He has distinct, eagle-like wings. One wing is red, white, and green—the colors that would eventually become the Mexican flag, though back then they had different symbolic meanings related to the earth and the heavens.

The angel’s expression is crucial. He isn't struggling to hold her up. He’s doing it with ease. His arms are spread wide, mimicking the gesture of an orator or someone presenting a gift. When drawing La Virgen de Guadalupe, treat the angel as a foundation, not an afterthought.

The Color Palette Nobody Talks About

If you go to a craft store and buy "Gold" paint, it’s probably too yellow. The gold in the Guadalupe image is muted. It’s an earthy, ochre-tinted gold.

The dress underneath the mantle is a soft rose-pink. But it isn't plain. It’s covered in "floral" designs that aren't actually flowers. They are tepetl symbols—Nahuatl glyphs for mountains and rivers. If you look at them closely, they look like hearts with stems. These symbols told the indigenous people that this woman was a "living map" of their land.

When you're sketching these patterns, don't worry about being perfectly symmetrical. The original image has a "hand-stamped" feel to it. It’s organic. It’s messy in a way that feels intentional.

Common Pitfalls for Modern Artists

Most people make her look too old. Or too young. She is meant to be a teenager—roughly 14 to 16 years old. If you give her heavy cheekbones or deep wrinkles, the "Virgen" aspect disappears. Keep the jawline soft.

Another huge error? The eyes.

The eyes of the Virgin are famously complex. Ophthalmologists have used high-resolution scans to claim they see reflections of people in the pupils. Whether you believe that or not, it means the eyes should have depth. Don't just draw two black dots. Use a tiny bit of white for a "catchlight" to make her look like she's looking back at you.

Step-by-Step Focus: Building the Layer

- The Silhouette: Start with a long, almond-shaped oval for the entire body. The top should be slightly narrower than the bottom where the mantle pools at her feet.

- The Head Tilt: Draw a vertical line through the center of your oval, then tilt it about 15 degrees to the right. That’s your alignment for the face.

- The Black Sash: This is vital. She is wearing a black sash around her waist. In Aztec culture, this indicated pregnancy. It’s a small detail, but without it, it's not Guadalupe. It’s just a lady in a cloak.

- The Rays: Start from the center and work your way out. Alternate between a straight spike and a wavy one. Don't crowd them.

- The Mantle Stars: Focus on the edges first. The stars follow the folds of the fabric, so if the cloak curves, the star pattern should curve too.

Honestly, the most important thing is the "vibe." This isn't a fashion illustration. It’s a devotional piece. If you’re too focused on making it "perfect," you might lose the soul of it. The original tilma is made of coarse cactus fiber; it’s rough. If your drawing is a bit raw, that actually fits the history better than a hyper-polished Pixar version.

Beyond the Paper: What to Do Next

Once you’ve finished drawing La Virgen de Guadalupe, you have to decide on the finish. Many artists use gold leaf for the rays. It catches the light in a way that paint just can't. If you're working digitally, use a "glow" or "bloom" effect on the mandorla to simulate that radiating energy.

If you're serious about mastering this:

- Study the Nican Mopohua. It’s the 16th-century account of the apparitions. It describes her clothing in detail that helps you understand why you're drawing what you're drawing.

- Look at the work of Jorge Sánchez-Hernández. He’s one of the most respected modern iconographers who focuses on the "exactness" of the image.

- Practice the "fold" of the mantle. The way it drapes over her forehead is a very specific shape—almost like a heart.

Your next move is to focus on the texture. Instead of a smooth gradient, try using cross-hatching or a "linen" brush if you're on Procreate. This mimics the rough texture of the original agave fiber. This isn't just an art project; it's a 500-year-old conversation. Respect the symbols, get the turquoise right, and remember that the sash isn't just a belt—it’s the whole story.