You’ve probably seen the headscarves. You’ve definitely seen the decaying wallpaper. When people bring up Edith Ewing Bouvier Beale, they usually start with the cats, the trash, and the 1975 Maysles brothers documentary that turned a pair of high-society recluses into camp icons. But honestly, Big Edie wasn't just a "crazy aunt" hiding out in a Hamptons mansion. She was a trained soprano with a rebellious streak that would’ve made a modern-day rockstar blush.

People love to gawk at the ruins of Grey Gardens. They see the 28 rooms falling apart and assume they're looking at a tragedy. It’s more complicated than that. Edith was a woman who basically checked out of a social system that never really had a place for her talent. She was the aunt of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, sure, but she was also a woman who chose her own weird, isolated reality over the suffocating expectations of the 1920s elite.

The High-Society Rebel You Don’t Know

Before the raccoons moved into the walls, Edith Ewing Bouvier Beale was the life of the party. Or, at least, she tried to be. Born into the wealthy Bouvier family in 1895, she was expected to marry well, stay quiet, and host perfect dinner parties. She did the marriage part—wedding Phelan Beale in 1917—but she was terrible at the "stay quiet" bit.

She wanted to be a professional singer. In the world of the Bouviers, "professional" was a dirty word for a woman. It was okay to sing for guests in your parlor, but recording an album? Touring? That was scandalous. Edith didn't care. She spent a fortune on singing lessons and spent her days practicing scales while her marriage crumbled.

Her husband, Phelan, eventually got fed up. He moved to a different house, sent a telegram to notify her of their divorce, and left her with a measly alimony and a massive house in East Hampton. That house was Grey Gardens.

Why the Money Ran Out

It’s a common misconception that she was always penniless. She had a trust, but it was managed by men who didn't exactly have her best interests at heart. By the 1960s, the money was basically gone. Edith and her daughter, "Little" Edie, were living in a house that cost more to heat than they had in the bank.

But here’s the thing: Edith didn't seem to mind the grime as much as the neighbors did. She had her records. She had her memories. She had a daughter who, despite their constant bickering, was her entire world. They created a private universe where the rules of the outside world—things like "sanitation" or "property taxes"—didn't really apply.

The Grey Gardens Scandal and the Jackie O Connection

In 1971, the health department showed up. The place was a biohazard. The Suffolk County Health Commission threatened to evict the Beales, and the story hit the tabloids. "Jackie’s Aunt Living in Squalor!" was the vibe of the headlines. It was a massive embarrassment for the Kennedy clan.

Jackie Onassis eventually stepped in. She paid roughly $30,000 to clean the place up, install new plumbing, and haul away truckloads of garbage. It saved the Beales from being homeless, but it didn't change their lifestyle. Edith Ewing Bouvier Beale wasn't going to start hosting tea parties just because the toilets worked again.

The Documentary That Changed Everything

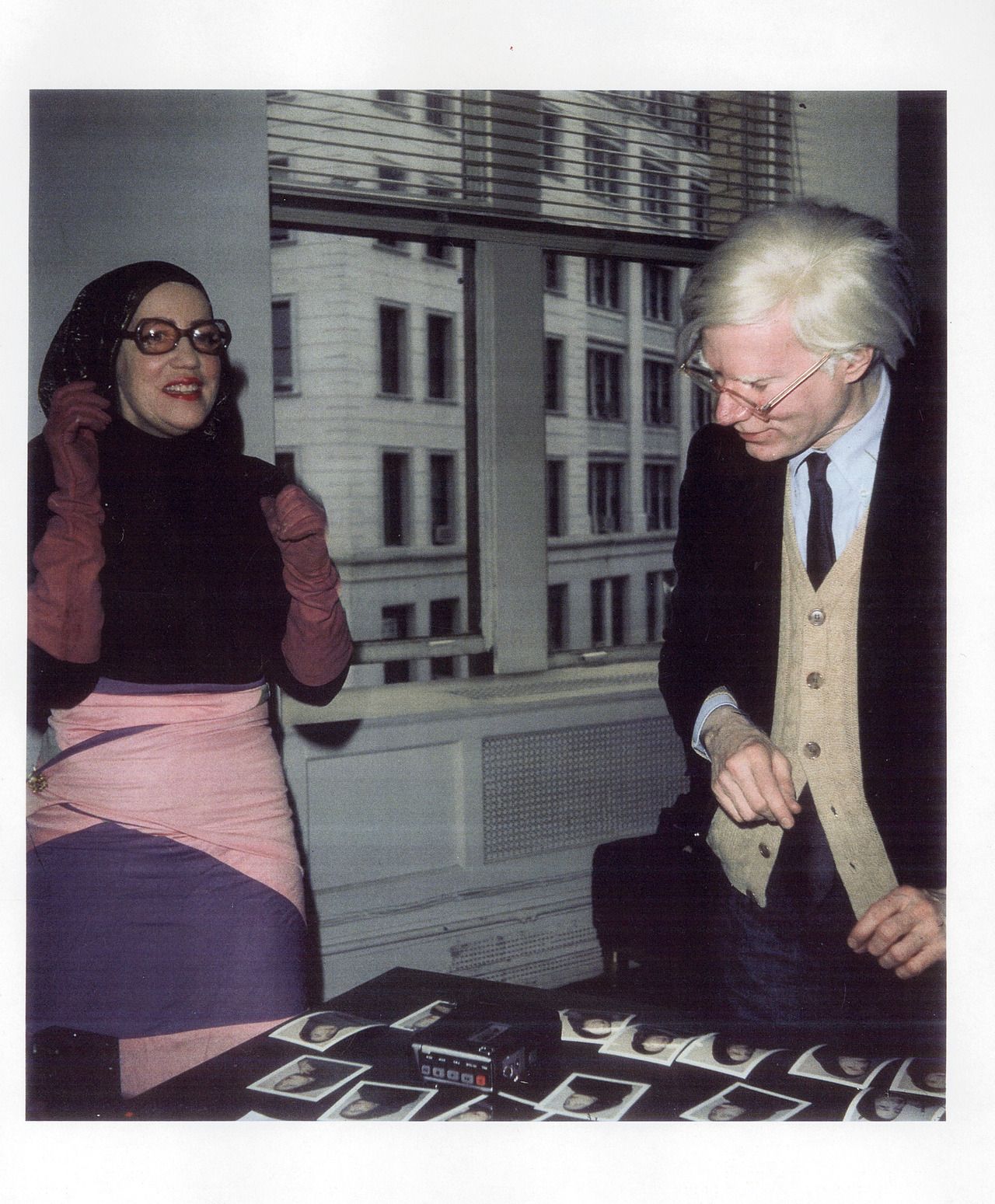

When Albert and David Maysles showed up a few years later, they weren't looking for a horror story. They found a love story. A weird, codependent, musical love story.

The film Grey Gardens is why we’re still talking about Edith today. It captured her lying in bed, surrounded by cat food cans and newspapers, singing "Tea for Two" with a voice that was still surprisingly clear. She was 79 years old and still performing. She wasn't a victim of the camera; she was its star. She knew exactly what she was doing.

Critics at the time were divided. Some thought the filmmakers were exploiting two mentally ill women. Others saw it as a raw portrait of Bohemian survival. If you watch it closely, Big Edie is the one in control. She’s the one directing the scenes, telling her daughter what to wear, and making sure the lighting is right. She never lost her sense of "the stage."

Setting the Record Straight on the "Madness"

Was Edith Ewing Bouvier Beale mentally ill? It’s a label people love to slap on her. But psychologists and historians who have studied the Beales—like Lee Radziwill’s biographers—often point out that Edith was more likely a victim of "eccentricity as a defense mechanism."

- She refused to conform: In her era, a woman who didn't care about a manicured lawn was "crazy."

- Isolation was a choice: She found the Hamptons social scene boring and vapid.

- The "hoarding" was complex: It wasn't just trash; it was a physical manifestation of her refusal to let go of her past.

She lived in that house until her death in 1977. Even on her deathbed at Southampton Hospital, she told Little Edie that she had nothing left to say because "it's all in the film." She knew the documentary was her legacy. She had finally become the professional performer she wanted to be back in 1920.

🔗 Read more: Latest Halle Berry Pictures: Why Her 2026 Look Is Turning Heads

Why Big Edie Still Matters in 2026

We live in an age of curated perfection. Instagram feeds are polished, houses are staged, and everyone is terrified of looking "messy." Edith Ewing Bouvier Beale is the ultimate antidote to that. She was messy. She was loud. She was unapologetically herself in a house that was literally falling down around her.

She reminds us that the "American Dream" of a white picket fence and a quiet life isn't for everyone. Some people want to live in a jungle of vines and cats, singing songs to the walls. And honestly? There’s a certain kind of dignity in that. She didn't want pity. She wanted an audience.

Real Evidence of Her Influence

- Fashion: Marc Jacobs and John Galliano have both cited the Beales' "found fashion" as inspiration for major collections.

- Theater: The Tony-winning musical Grey Gardens brought her story to Broadway, humanizing her struggle for independence.

- Pop Culture: From RuPaul's Drag Race to countless indie films, the image of the defiant, eccentric woman in the headscarf is shorthand for "I don't care what you think."

Lessons from the Life of Edith Ewing Bouvier Beale

If you're looking for a takeaway from Big Edie’s life, it’s not about how to keep a clean house. It's about the cost of authenticity. Edith paid a high price for her lifestyle—isolation, poverty, and public ridicule—but she never seemed to regret it.

To truly understand her, you have to look past the ruin of the house. Look at the way she held her head. Look at the way she spoke about her music. She was a woman who was "too much" for her time, so she built a world where she was just enough.

How to Explore the Beale Legacy Further:

- Watch the 1975 Documentary: Don't watch it as a tragedy. Watch it as a performance piece. Pay attention to Edith’s wit; she’s often the smartest person in the room.

- Read "The Big Edie" Letters: Various archives and biographies of the Bouvier family contain letters that show her sharp intellect and deep frustration with her social standing.

- Listen to her recordings: Some of the original audio of her singing has been preserved. It’s haunting, imperfect, and deeply personal.

- Visit East Hampton: You can see Grey Gardens from the street (it’s been fully restored by subsequent owners like Sally Quinn and Ben Bradlee). It’s a beautiful house now, but the ghost of Edith’s defiance still lingers in the salty air.

Edith Ewing Bouvier Beale didn't need a comeback. She never left. She just waited for the rest of us to catch up to her frequency. In a world that demands conformity, being a "rebel in a headscarf" is a radical act of self-love.

📖 Related: Lo que realmente pasó con el supuesto video íntimo de Beele y Isabella Ladera

Practical Next Steps for Fans and Researchers:

- Digital Archives: Search the Library of Congress for "Bouvier family" records to see the contrast between Edith’s early life and her later years.

- Documentary Supplements: Check out The Beales of Grey Gardens, a follow-up film featuring deleted footage that gives a more rounded view of their daily lives.

- Biographical Reading: Pick up Gerry Gardens: The Relationship Between a Mother and a Daughter for a deeper dive into the psychological bond that kept them together for decades.