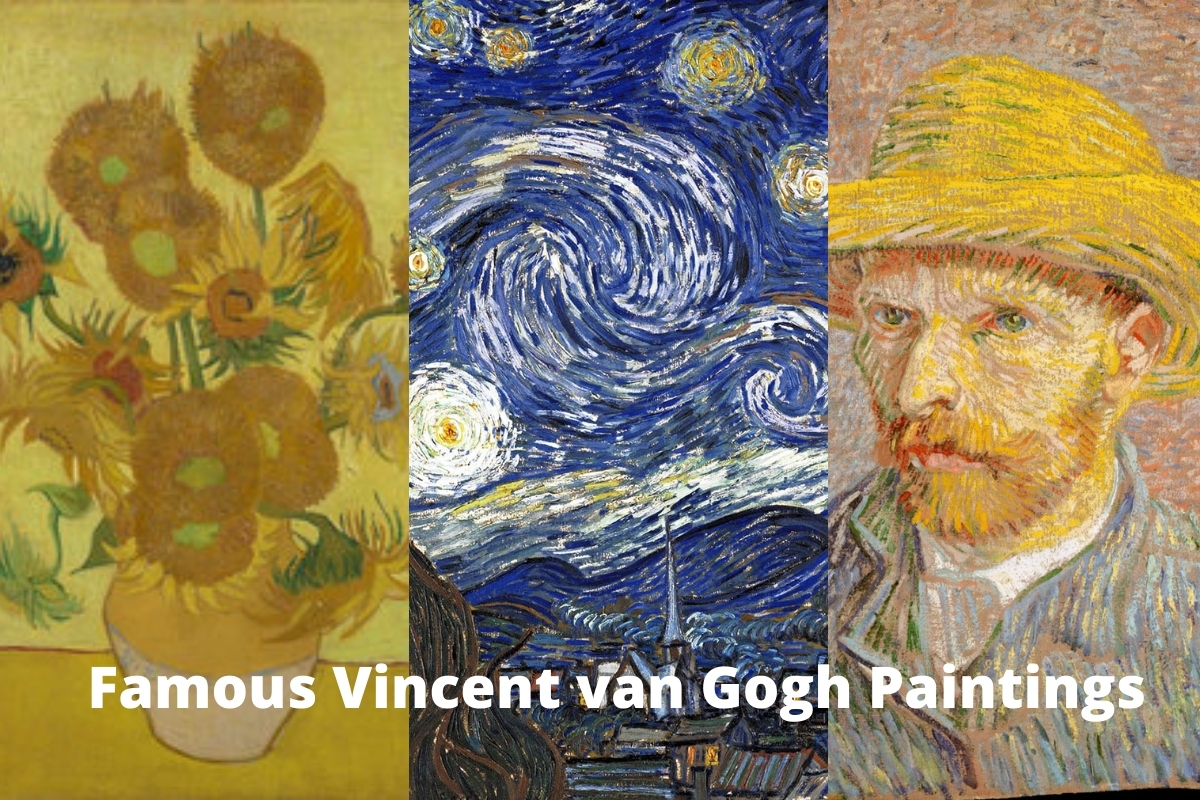

Everyone thinks they know Vincent. They know the ear thing. They know the yellow sunflowers. They know the "starry" swirls that look like a psychedelic trip before psychedelics were a thing. But honestly, looking at famous paintings by Van Gogh through the lens of a "tortured artist" trope does a massive disservice to the actual work. It wasn't just madness. It was math. It was deliberate, grueling, back-breaking labor.

Vincent van Gogh didn't even start painting until his late twenties. Imagine that. He failed at being a preacher, failed at being a bookseller, and then, in a fit of "I have to do something," he decided to master the most difficult medium on earth. He was a late bloomer who burned out in a decade. But what a decade.

The Starry Night: It's Not What You Think

You've seen it on socks. You've seen it on coffee mugs. The Starry Night is basically the "Mona Lisa" of the post-impressionist world. Vincent painted it in 1889 while he was staying at the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence.

Here is the kicker: he actually thought it was a failure.

In his letters to his brother Theo, Vincent barely mentions it. When he does, he sort of shrugs it off as an "exaggeration." He was frustrated because he couldn't paint from nature at night, so he had to rely on his memory and imagination—something he usually hated doing. He was a realist at heart, believe it or not.

The cypress tree in the foreground? That’s not just a cool shape. In the 19th century, cypresses were symbols of mourning and death. By placing it so prominently, Vincent was literally connecting the earth to the sky, life to the afterlife. Scientists have since analyzed the "turbulence" in the clouds and found they align almost perfectly with the mathematical structures of fluid flow. He was capturing the physics of the universe without a calculator. Just a brush and a lot of lead-heavy paint.

✨ Don't miss: How Much Is It to Rent a Tuxedo? What to Actually Expect at the Register

Sunflowers and the Obsession with Yellow

Why sunflowers?

For Van Gogh, the sunflower was a symbol of gratitude. He didn't just paint one version; he did a whole series of them to decorate a bedroom for his friend Paul Gauguin. He wanted to impress the guy. He wanted to show off his "Symphony in Blue and Yellow."

The yellow he used was a specific pigment called Chrome Yellow. It was a relatively new invention back then. The tragedy is that this specific pigment is chemically unstable. It darkens over time when exposed to light. So, the vibrant, glowing yellows we see today in the Van Gogh Museum are actually a muted version of what Vincent originally slapped onto the canvas. They were even brighter. Think about that. The paintings were loud. They were screaming.

Gauguin eventually showed up, they fought, the ear incident happened, and the friendship imploded. But those sunflowers remained. They represent a brief moment of hope before the shadows got too long.

The Bedroom: A Study in "Rest"

If you look at The Bedroom (the Arles version), the perspective is totally wonky. The bed looks like it’s sliding off the floor. People used to think he drew it that way because he was losing his mind.

Actually, the room was just shaped like that.

Architectural surveys of the "Yellow House" in Arles showed that the walls were built at an awkward angle. Vincent wasn't hallucinating; he was being an accurate reporter of his surroundings. He told Theo he wanted the colors—pale violet walls and a blood-red floor—to induce a feeling of "absolute rest."

Ironically, the painting feels anything but restful to a modern viewer. It feels cramped and intense. But to a man who had spent his life moving from one dingy boarding house to another, a room of his own with a sturdy wooden bed was the ultimate luxury.

Cafe Terrace at Night: The Black-less Night

Check out Cafe Terrace at Night. Look really closely at the shadows.

There is no black paint in that piece. None.

Vincent was obsessed with the idea that the night was actually full of color. He used deep blues, violets, and greens to create the darkness. He wrote that the night is "much more alive and richly colored than the day." This was a revolutionary way of seeing. While other painters were using black and grey to denote shadow, Vincent was using fire-orange and sulfur-yellow.

He painted this one on-site, outdoors, in the dark. He supposedly pinned candles to the brim of his straw hat so he could see his palette. He was a human lighthouse, standing on the corner of the Place du Forum, capturing the glow of a gas-lit evening while people walked past him like he was a local eccentric. Which, to be fair, he was.

🔗 Read more: Happy endings at spa: The Legal Reality and Why It Matters for Your Safety

The Myth of the "Suicide Painting"

We have to talk about Wheatfield with Crows.

For a long time, the narrative was that this was his final painting—a frantic, dark suicide note in oil paint. The turbulent sky and the crows flying away were seen as omens.

The scholarship has shifted.

We now know, thanks to researchers at the Van Gogh Museum like Louis van Tilborgh, that he painted several works after this one. Tree Roots is now widely considered his actual final work. Wheatfield with Crows wasn't a goodbye; it was an exploration of sadness and extreme loneliness, sure, but it was also about the power of the countryside. He saw the fields as "healthful and restorative."

He wasn't always painting his death; he was often painting his attempt to stay alive.

The Self-Portraits: A Mirror to the Soul

Vincent couldn't afford models. That’s the boring, practical reason why there are so many famous paintings by Van Gogh featuring his own face. He was broke.

If you look at the series of self-portraits from 1886 to 1889, you see a man physically eroding. The early ones in Paris show a well-dressed, bourgeois-looking guy with a decent haircut. Fast forward a few years, and the gaze is haunted. The brushstrokes become rhythmic, almost like a thumbprint.

He used his own face as a laboratory. He experimented with "complementary colors"—putting red hair against a green background to make the colors "vibrate." It worked. When you stand in front of these at the Musée d'Orsay, the air feels like it's humming.

How to Actually Look at a Van Gogh

If you ever get the chance to see these in person, don't just look at the image. Look at the "impasto."

Vincent applied paint so thick it’s basically 3D. In some spots, he didn't even use a brush; he squeezed the tube directly onto the canvas or used a palette knife to sculpt the oil. It’s messy. There are bits of sand and dust trapped in the dried paint because he worked outside in the wind.

That’s the "human" part of the art. It’s the physical record of a man who was in a hurry. He knew he didn't have much time.

Putting This Knowledge into Practice

If you're looking to dive deeper into the world of Vincent, don't just scroll through Instagram.

- Read the Letters: Go to the Van Gogh Letters project. It’s a free, searchable database of every letter he wrote. It’s better than any biography. You get to hear his voice—intelligent, articulate, and deeply sensitive.

- Visit Digitally: Use the Google Arts & Culture high-resolution scans. You can zoom in until you see the individual cracks in the paint (the "craquelure").

- Track the Timeline: Stop looking at his work as one big "style." Look at the "Dutch period" (dark, earthy, muddy) versus the "Arles period" (bright, yellow, explosive). The transition is where the magic happens.

- Check the Provenance: When you see a "Van Gogh" in a small museum, check its history. Because he was so prolific and his style so distinct, fakes have entered the market for decades. The "Bredius" era of authentication was a mess, and we're still cleaning it up today.

Vincent van Gogh only sold one painting during his life (The Red Vineyard). Today, he's a billion-dollar industry. But beyond the money and the fame, the reason these paintings still matter is that they are honest. They don't try to be pretty. They try to be true. Whether it's a pair of battered old shoes or a sprawling starry sky, he was just trying to show us what it felt like to be awake in the world.

Go look at a print of The Sower today. Look at the sun—that giant, golden disc. It’s not a sun; it’s a heartbeat. Once you see it that way, you can’t go back to seeing him as just a guy who cut off his ear. He was a guy who saw the light in everything, even when he was sitting in the dark.