It starts as a nuisance. You skip a day, then three, then a week. You try the usual suspects—extra water, a bit more fiber, maybe that dusty bottle of magnesium citrate from the back of the cabinet. But then, the sensation changes. It isn't just "not going" anymore. It feels like a literal brick is sitting in your pelvis. This is the reality of fecal impaction, a condition that turns ordinary constipation into a legitimate medical emergency.

Honestly, it's a topic people find embarrassing, so they wait. They wait until the pain is white-hot or until they start experiencing "overflow diarrhea," which is one of the most confusing symptoms in all of gastroenterology. You think you have a loose stool, but in reality, liquid waste is just leaking around a massive, hardened mass that's physically stuck in your rectum. It's a bottleneck. A bad one.

Understanding the Mechanics of Fecal Impaction

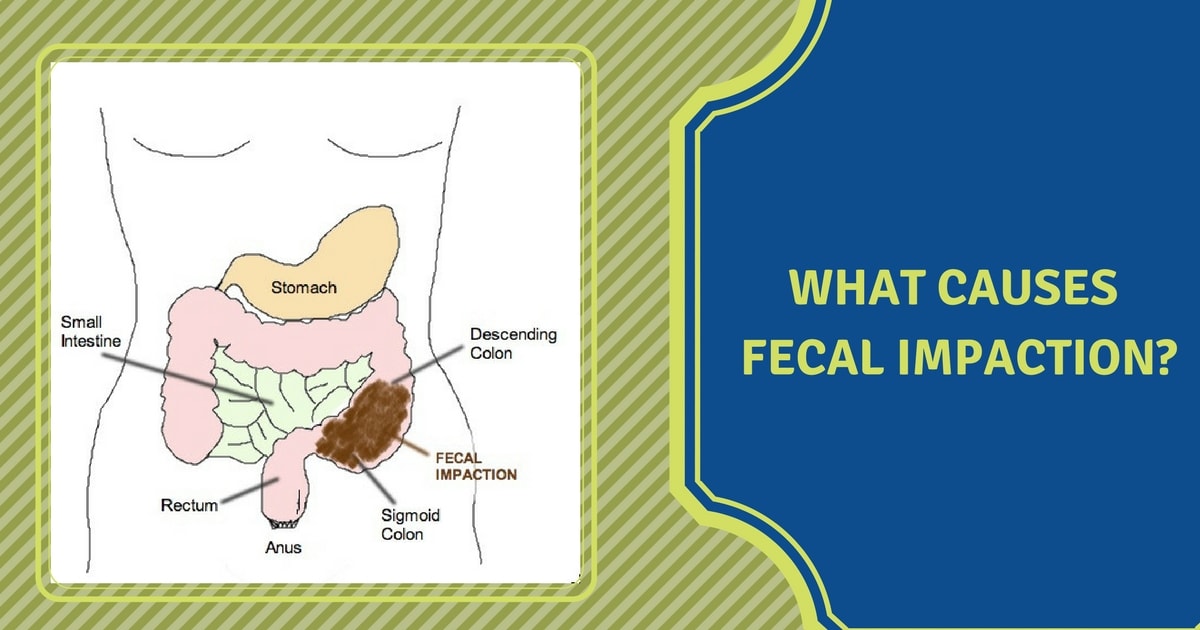

To understand why this happens, we have to look at the colon's primary job: water absorption. Your large intestine is a master at recycling fluid. When waste sits in the colon for too long, the body keeps pulling water out of it. The longer it stays, the drier it gets. Eventually, the stool becomes so hard, so dehydrated, and so large that the normal muscular contractions of the gut—peristalsis—simply cannot move it.

It’s stuck.

Dr. Lawrence Schiller, a past president of the American College of Gastroenterology, has often noted that chronic constipation is the leading precursor here. But it isn’t the only one. Sometimes, the hardware just stops working correctly. If the nerves in the distal colon aren't firing, or if the pelvic floor muscles are dyssynergic (meaning they push when they should relax), you’re on a fast track to an impaction.

Who is actually at risk?

While anyone can get hit with this, it disproportionately targets specific groups. The elderly are at the highest risk. Why? Because as we age, gut motility naturally slows down. Mix that with decreased physical activity and, often, a cocktail of medications that dry out the system, and you have a recipe for disaster.

Then there are the medications. Opioids are the biggest culprits. Opioid-induced constipation (OIC) is so common because those drugs bind to receptors in the gut, effectively paralyzing the movement. Anticholinergics, certain blood pressure meds (like calcium channel blockers), and even heavy doses of iron supplements can contribute.

👉 See also: Ideal Weight 5'2 Female: Why the Numbers on Your Scale Are Kinda Lying

The Symptoms Nobody Tells You About

You expect the abdominal pain. You expect the bloating. But fecal impaction has some weird, almost counterintuitive red flags.

Take "paradoxical diarrhea." This is the one that trips everyone up. You might think you've finally "broken through" because you're seeing liquid stool, but that liquid is actually a sign of a severe blockage. The body is trying to bypass the obstruction. It’s a false sense of relief.

Then there’s the pressure on other organs. A large mass in the rectum can press against the bladder, leading to urinary frequency or even incontinence. You might feel a persistent urge to push, similar to labor, but nothing happens. In severe cases, the distension of the colon can be so extreme that it affects your breathing or causes heart palpitations because the diaphragm is being pushed upward.

Identifying the Danger Zone

When does a "stuck" feeling become a "go to the ER" feeling?

- Vomiting that smells like... well, waste.

- A rigid, board-like abdomen.

- Rapid heart rate and dehydration.

- Confusion, especially in older adults (this is often a sign of impending sepsis or severe electrolyte imbalance).

If you’re at this point, home remedies are off the table. You need professional intervention before the colon wall becomes ischemic or, worse, perforates.

How Doctors Actually Fix It

If you end up in a clinical setting, the first step is usually a digital rectal exam. It’s exactly what it sounds like, and no, it isn’t fun. But it’s the most direct way for a provider to confirm that the mass is indeed sitting in the vault.

From there, the strategy is "top-down and bottom-up."

The "bottom-up" approach usually involves enemas—saline, mineral oil, or even milk and molasses in some hospital protocols. These are meant to soften the exterior of the mass. If that fails, manual disimpaction is necessary. A clinician literally has to break up the mass by hand. It’s a gritty reality of medicine that doesn't make it into the TV shows, but it is life-saving.

The "top-down" approach uses heavy-duty osmotic laxatives like polyethylene glycol (Miralax) in large doses. The goal is to flood the colon with water from above to help slide the mass out.

The Long-Term Fallout

You can’t just clear an impaction and go back to your old life. The colon is a muscle. When it gets stretched out by a massive impaction, it becomes "megacolon." This means the muscle is stretched thin and loses its tone. It won’t "snap back" immediately.

This creates a cycle. The weakened colon is even less efficient at moving stool, which leads to... another impaction. Breaking this cycle requires months of bowel retraining, often involving scheduled bathroom trips, high-dose stool softeners, and sometimes physical therapy for the pelvic floor.

Why Fiber Isn't Always the Answer

Here is a piece of advice that might go against everything you've heard: if you are currently impacted, stop eating fiber. Fiber is a bulking agent. If the "exit" is blocked by a hard mass, adding more bulk to the "entry" just creates more pressure. It’s like adding more cars to a traffic jam that is already at a dead stop. Fiber is great for prevention, but once you’re in the middle of an impaction crisis, you need liquids and lubricants, not more roughage.

Practical Steps to Avoid the Rebound

Preventing a second round of fecal impaction is about consistency and biological cues.

Hydration is non-negotiable. You need enough water so that your colon doesn't feel the need to scavenge every drop from your waste. If your urine isn't pale yellow, you aren't drinking enough.

Check your meds. Talk to your doctor about every single pill you take. If you’re on an antidepressant or a diuretic that’s slowing things down, there might be an alternative.

📖 Related: Long term use of insulin ICD 10: Getting the Codes Right Without the Headache

The Squatty Potty isn't a gimmick. Human anatomy is designed to defecate in a squatting position. This straightens the anorectal angle. When we sit on a standard toilet, that angle is kinked, making it harder to pass stool without straining. Use a stool to lift your knees above your hips.

Movement matters. Even a 15-minute walk after dinner stimulates the "gastrocolic reflex." This is your body's signal to move things along.

Your Action Plan for Bowel Health

- Monitor the Frequency: If you go more than three days without a bowel movement, start an osmotic laxative (like Miralax) immediately. Don't wait for pain.

- Audit Your Bathroom Habits: Stop scrolling on your phone. Sit, try for 5-10 minutes, and if nothing happens, get up. Straining for long periods causes hemorrhoids and rectal prolapse, which make future impactions more likely.

- The Magnesium Factor: Many people find that a daily magnesium citrate or oxide supplement keeps the stool soft enough to prevent the "drying out" phase.

- Listen to the Urge: When your body says it's time, go. Ignoring the urge causes the rectum to desensitize over time, leading to chronic retention.

Fecal impaction is a serious physical roadblock. Treating it requires a mix of immediate mechanical clearing and long-term behavioral shifts. If you suspect you're currently impacted and are experiencing abdominal distension or vomiting, seek medical attention at an urgent care or emergency room immediately. Recovery is possible, but it starts with acknowledging that your "regularity" is a vital sign that deserves your full attention.