Money doesn't just appear. Well, actually, sometimes it does. If you've ever wondered why your mortgage rate suddenly spiked or why the stock market threw a collective tantrum on a random Wednesday, the answer usually lies in a room in Washington D.C. where people talk about federal open market operations. It sounds incredibly dry. It sounds like something you’d find in a textbook that smells like a basement. But honestly? It is the most powerful tool in the global economy.

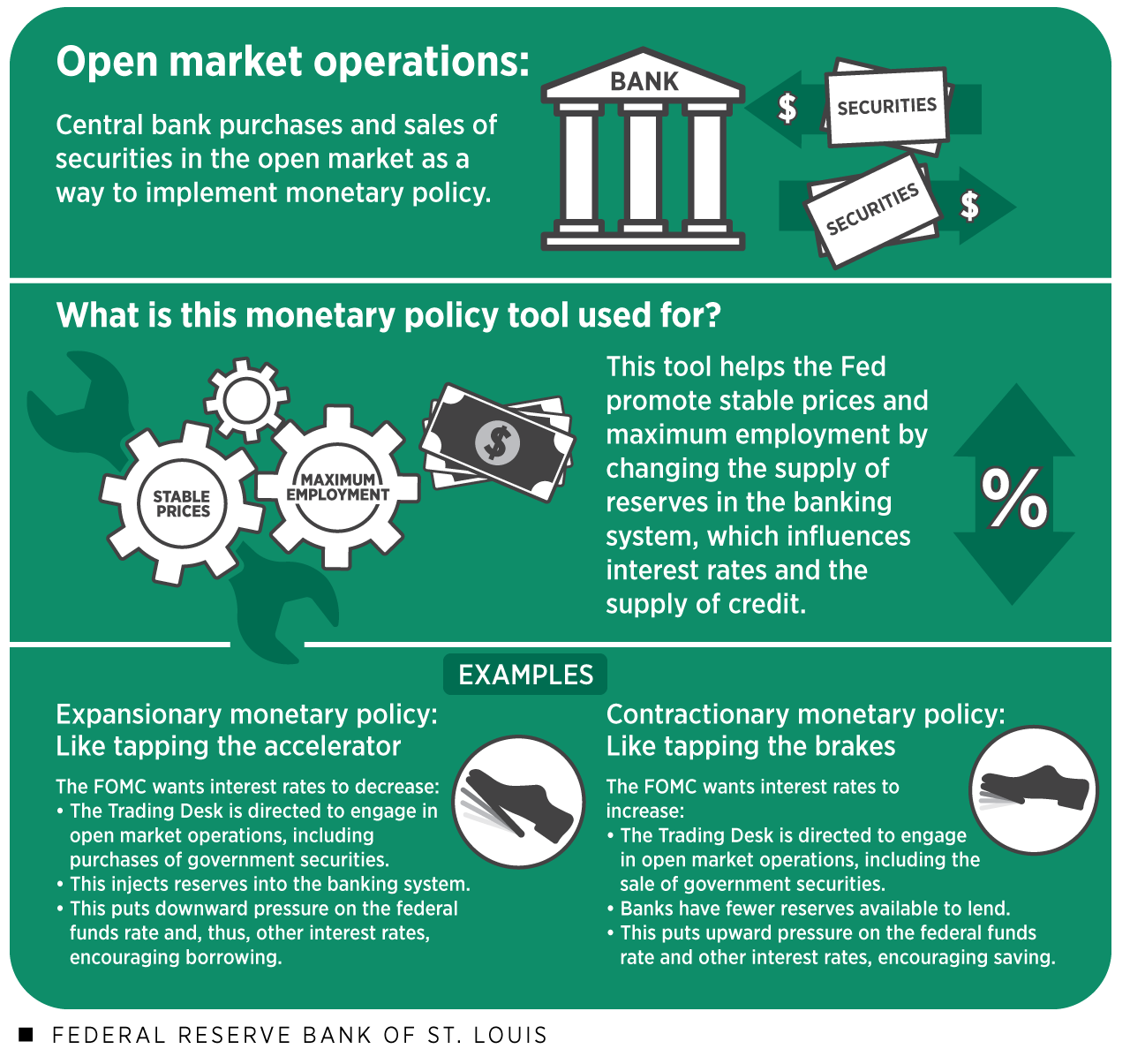

The Federal Reserve—the Fed—doesn't just print physical dollar bills and throw them out of helicopters. That’s a myth. Instead, they engage in a very specific, very calculated game of buying and selling government bonds. When the Fed wants to grease the wheels of the economy, they buy. When they want to cool things down because your grocery bill is getting out of hand, they sell. It's basically the world's biggest thermostat.

How Federal Open Market Operations Actually Work

Think of the economy like a giant bathtub. The water is the "liquidity"—the cash sloshing around that banks can lend to you for a car or a house. Federal open market operations (OMO) are the faucet and the drain.

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meets eight times a year. They look at the data. They argue. They drink a lot of coffee. Then, they decide on a target for the federal funds rate. But here is the kicker: the Fed doesn't just "set" the rate by decree. They have to nudge the market to get it there. They do this through the Trading Desk at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

🔗 Read more: Alphabet Q1 2023 EPS: What the Numbers Actually Told Us About Google’s Survival

When the Fed buys Treasury securities from big banks (primary dealers like JPMorgan or Goldman Sachs), they pay for them by adding credits to those banks' reserve accounts. They are basically creating digital money out of thin air. Now the banks have more cash. When banks have more cash, they want to lend it out. Competition to lend drives interest rates down. You get a cheaper loan. The economy speeds up.

Conversely, if the Fed thinks things are getting "too hot," they do the opposite. They sell those Treasuries back to the banks. The banks pay for them with their reserves. Suddenly, there is less cash in the system. Lending gets tighter. Interest rates climb. This is the "drain" in the bathtub.

The Nuance of Permanent vs. Temporary OMO

It's not all just one big buy-and-sell. The Fed uses different "vibes" for different problems.

Permanent OMO is exactly what it sounds like. They buy securities and hold them. This is usually to account for the fact that as the economy grows, people just naturally need more currency in circulation. It’s the baseline.

Then you have the temporary stuff. These are called Repurchase Agreements (repos) and Reverse Repos. A repo is basically a short-term loan. The Fed buys a security today with an agreement to sell it back tomorrow or next week. It’s a quick shot of adrenaline to the banking system. Reverse repos are the opposite—the Fed "borrows" money from the market to soak up excess cash. Recently, the Fed’s Reverse Repo Facility (RRP) has been huge, sometimes holding over $2 trillion as money market funds looked for a safe place to park cash.

Why Should You Actually Care?

Most people ignore this because it feels like "banker stuff." But it hits your wallet faster than almost anything else.

If the Fed is aggressive with federal open market operations to tighten the money supply, your credit card interest rate goes up. Your dreams of refinancing your home go on ice. On the flip side, during the 2008 crash and the 2020 pandemic, the Fed went into "Quantitative Easing" (QE) mode. This is basically OMO on steroids. They didn't just buy short-term debt; they bought long-term bonds and mortgage-backed securities. They flooded the zone.

The result? Mortgage rates hit historic lows. The stock market rocketed. But the side effect—as we've all felt at the gas pump and the cereal aisle—can be rampant inflation. It’s a delicate balance, and honestly, even the experts at the Fed don't always get the timing right. Jerome Powell and the rest of the board are constantly second-guessing whether they've drained too much or poured too much.

The "Primary Dealer" Gatekeepers

You can't just call up the Fed and sell them your savings bonds. The Fed only deals with a specific list of "primary dealers." These are the titans of Wall Street. This relationship is controversial for some. Critics argue that this system gives the biggest banks a massive advantage and first dibs on the "new" money entering the system.

It’s a fair point. By the time that liquidity trickles down to a small business in Ohio or a freelancer in Seattle, the big banks have already used it to shore up their balance sheets or invest in high-yield assets. This is often where the "wealth gap" conversation starts, even if the Fed's primary goal is just "price stability and maximum employment."

Misconceptions About the "Money Printer"

You’ll see memes on X (formerly Twitter) about the Fed "printing money go brrr." It’s funny, but it’s technically wrong.

- The Fed doesn't print physical cash. The Bureau of Engraving and Printing does that.

- OMO is an exchange of assets. When the Fed buys a bond, the bank loses a bond but gains cash. The total value of the bank's assets doesn't necessarily change instantly; the form of the asset changes from a "locked" bond to "liquid" cash.

- The Fed isn't spending taxpayer money. This is a huge one. When the Fed conducts federal open market operations, it uses its own balance sheet. In fact, the Fed usually makes a profit on the interest from the bonds it holds, and it sends most of that profit back to the U.S. Treasury.

Real World Example: The 2020 Pivot

In March 2020, the world stopped. Markets froze. Nobody wanted to lend to anyone because nobody knew if the world was ending. The Fed didn't just step in; they leaped. They used OMO to buy trillions in securities at a pace never seen before.

This kept the gears from grinding to a halt. It prevented a total banking collapse. But it also set the stage for the massive inflation spike of 2021 and 2022. It’s the ultimate "no free lunch" scenario. By using federal open market operations to save the floor from falling out, they accidentally built a ceiling that was way too high.

📖 Related: Dollar to Ruble Today: What Most People Get Wrong About the 78 Mark

What to Watch Moving Forward

The Fed is currently in a phase of "Quantitative Tightening" (QT). This is the "selling" part of the cycle, or more accurately, letting bonds "run off" their balance sheet without replacing them.

- Watch the Yield Curve: If the Fed's operations aren't syncing up with what the market expects, the yield curve can invert. That’s usually a big red flag for a recession.

- The "Neutral Rate": Economists talk about a "r-star" or neutral interest rate. This is the Goldilocks zone where the economy isn't growing too fast or shrinking. The Fed uses OMO to try and find this invisible target.

- Liquidity Cracks: Sometimes, the Fed drains too much. In September 2019, the "repo market" suddenly broke. Interest rates for overnight loans spiked to 10% out of nowhere. The Fed had to jump back in and start buying again. It showed that even the Fed doesn't always know exactly how much "water" needs to stay in the bathtub.

Actionable Insights for the Non-Economist

So, what do you do with this info? You don't need a PhD to use this to your advantage.

Pay attention to the FOMC minutes. These are released a few weeks after every meeting. Don't look at the headline numbers; look for words like "accommodation" (they want to keep rates low) or "restrictive" (they want to keep rates high). If you see the Fed leaning toward more federal open market operations (buying), it's generally a "green light" for riskier assets like stocks or crypto.

Check your debt structure. If the Fed is in a tightening cycle (selling bonds), stop taking out variable-rate debt. Your "teaser" rate on that credit card or ARM mortgage is going to vanish faster than you think.

Understand the lag. Fed actions take 6 to 18 months to fully hit the "real" economy. If they start aggressive OMO today, you won't feel the full effect until next year. Plan your big purchases or business expansions with that delay in mind.

The Fed isn't some shadowy cabal—though it can feel like it. It's just a group of people trying to manage a chaotic system using a very large, very blunt hammer. Understanding federal open market operations is simply about knowing when that hammer is about to swing.

Next Steps for You:

Monitor the New York Fed’s "System Open Market Account" (SOMA) holdings. It’s public data. If you see the total assets declining steadily month-over-month, you know the Fed is pulling cash out of the system. This usually precedes a cooling market. Use this as a signal to build up your cash reserves and look for "sales" in the stock market once the cooling turns into a dip.