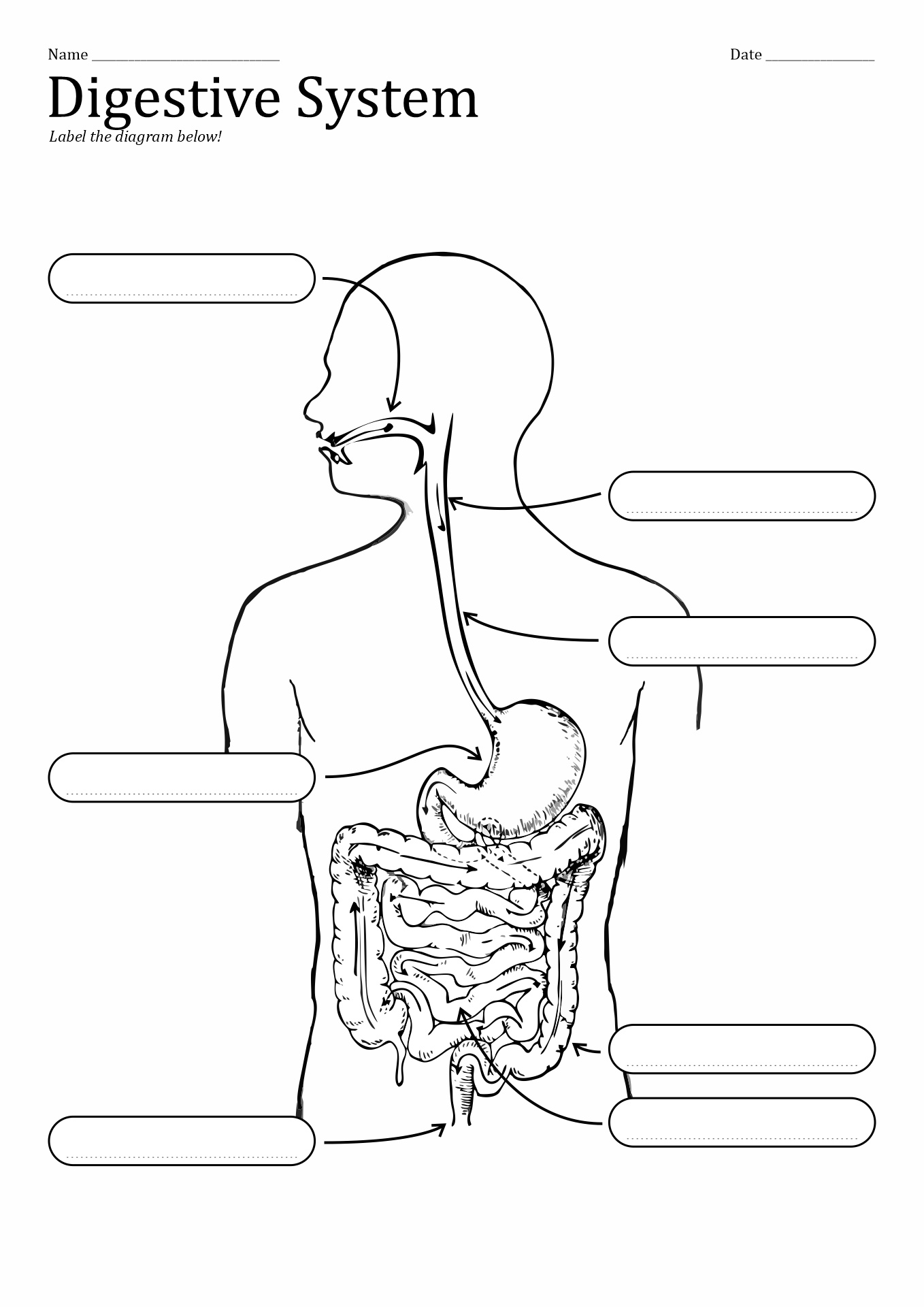

Let's be real. If you’re hunting for a digestive system diagram blank, you’re probably either a student staring down a biology final or a teacher trying to prep a lab that doesn’t bore everyone to tears. It’s one thing to see a colorful drawing in a textbook. It’s a totally different beast to sit there with a grayscale outline and try to remember if the gallbladder is tucked behind the liver or if it’s just floating somewhere near the stomach. It’s not. It’s definitely attached.

Memorization is hard.

Most people just stare at the page and hope for the best. But that’s why most people fail their anatomy quizzes. You’ve gotta get your hands dirty—metaphorically, hopefully.

A good digestive system diagram blank serves as a bridge. It takes that abstract mess of tubes and turns it into a map you can actually navigate. Honestly, the human body is basically just a very long, very complicated hose. Understanding how it’s coiled is the secret to passing your A&P exams.

Why a Digestive System Diagram Blank is Better Than Your Textbook

Textbooks are cluttered. They have too many arrows. They have tiny fonts. When you look at a finished diagram, your brain gets lazy because the answers are already there. You think you know it, but you don't. Testing yourself with a blank version forces your brain to retrieve information from scratch. This is called "active recall," and it's basically the only way to make information stick long-term.

Think about the esophagus. It looks simple enough, right? But on a digestive system diagram blank, you have to decide exactly where it transitions into the stomach. Is it at the diaphragm? Yes. Does that matter? If you're going into nursing or med school, you bet it does.

Mapping the Journey: From Mouth to... You Know

If you’re labeling your diagram, you should probably start at the top. The mouth is more than just teeth. You have salivary glands—the parotid, submandibular, and sublingual. If your diagram is detailed enough, it’ll have little spots for those. If not, you’re just looking at a hole in a face.

Then comes the pharynx. Most people skip this or confuse it with the larynx. Don't be that person. The pharynx is the hallway; the larynx is the voice box. Your digestive system doesn't care about your singing voice. It cares about moving that sandwich down the tube.

The stomach is where things get weird. It’s not just a bag. It’s got regions: the fundus, the body, the antrum, and the pylorus. When you’re filling out your digestive system diagram blank, try to draw the lines for these sections yourself if they aren't there. It helps you visualize where the acid is actually doing the heavy lifting.

- The Liver: The massive organ on the right.

- The Pancreas: Tucked behind the stomach, looking like a weird leaf.

- The Small Intestine: This is where the magic (and the absorption) happens.

- The Large Intestine: Mostly for water and making sure things "wrap up" properly.

Common Mistakes People Make When Labeling

Everyone messes up the accessory organs. They’re called "accessory" but you’d be in a lot of trouble without them. The liver, gallbladder, and pancreas are the big three.

I’ve seen so many students label the gallbladder as the kidney. Don't do that. The kidneys are way in the back, part of a different system entirely. The gallbladder is that tiny pear-shaped sac under the liver. On a digestive system diagram blank, it’s often just a small circle.

Another classic error is the small intestine versus the large intestine. It’s not about length; the small intestine is actually way longer (around 20 feet!). It’s about diameter. The large intestine—the colon—is wider and frames the small intestine like a picture frame. If you’re filling out a diagram, start by labeling the ascending, transverse, and descending colon first. It makes the middle part look less intimidating.

✨ Don't miss: IUD Pain After Insertion: What’s Actually Normal and When to Worry

The Science of Why Drawing it Out Matters

Dr. Priscilla Laws and other educational researchers have long advocated for "kinesthetic learning" in science. When you physically move your hand to label a digestive system diagram blank, you’re engaging different neural pathways than when you’re just reading.

It’s about spatial awareness.

You need to know that the duodenum is the first part of the small intestine and that it’s C-shaped. You need to see how the common bile duct connects the liver and gallbladder to that duodenum. If you can’t draw that connection on a blank page, you don't really understand the biliary system yet.

Getting Creative with Your Study

Don't just use a black pen. That’s boring. Use colors.

Blue for the organs that handle liquids. Red for the ones with high blood flow like the liver. Green for the gallbladder (because bile is actually green/yellow). When you use a digestive system diagram blank with a color-coding system, your brain starts to categorize the organs by function, not just by where they sit in the torso.

Honestly, some people even use play-dough. If you have a blank printout, try making the organs out of clay and sticking them onto the paper. It sounds like something for fifth graders, but I know med students who do this to memorize the complex layering of the mesentery. It works because it's tactile.

Finding the Right Blank Diagram for Your Level

Not all diagrams are created equal.

If you're in middle school, you probably just need the basics: mouth, stomach, intestines, liver.

If you're in college-level anatomy, your digestive system diagram blank better have space for the ileocecal valve, the hepatic portal vein, and the various sphincters (cardiac and pyloric).

Check the resolution before you print. There is nothing worse than a blurry diagram where the arrow for the appendix looks like it's pointing at the bladder. You want crisp lines. You want clear margins.

Beyond the Basics: The Microscopic View

Sometimes a digestive system diagram blank isn't enough. You might need a "blow-up" version of the intestinal wall. The villi and microvilli are what actually do the work of keeping you alive by absorbing nutrients.

If you can find a diagram that shows a cross-section of the small intestine, grab it. Labeling the mucosa, submucosa, muscularis externa, and serosa is next-level stuff. That's the difference between a B and an A in a histology-heavy course.

How to Test Yourself Effectively

- Print three copies of your digestive system diagram blank.

- Fill the first one out while looking at your notes.

- Wait an hour.

- Fill the second one out from memory. Check your mistakes.

- Wait until the next morning.

- Fill the third one out. If you get it all right, you actually know the material.

This is called "spaced repetition." It’s basically the gold standard for learning anatomy.

Final Thoughts on Mastering the Map

The digestive system is a masterpiece of biological engineering. It’s messy, it’s cramped, and it’s incredibly efficient. Using a digestive system diagram blank isn't just about passing a test; it’s about understanding the engine that keeps you running.

Next time you eat a taco, think about that diagram. Think about the mechanical digestion in the mouth, the chemical breakdown in the stomach, and the nutrient absorption in the jejunum. It makes the diagram feel a lot more real.

Start by downloading a high-quality PDF version of a blank diagram. Avoid the low-res JPEGs you find on random clip-art sites. Look for educational repositories or university biology department websites where the anatomical accuracy is vetted by experts. Once you have a clean template, grab a set of fine-liner pens and start from the top down. Focus on the junctions—the spots where one organ turns into another—as these are the most common areas for exam questions.