If you’re looking for Boston on a map of the US, you’re basically looking at the "upper right-hand corner" of the country. That's the simple version. But honestly, even if you know it's in Massachusetts, there is a lot more to its coordinates than just a pin on a digital screen. It’s tucked into a very specific notch on the Atlantic coast, and that jagged little harbor is the whole reason the city—and frankly, a huge chunk of American history—exists at all.

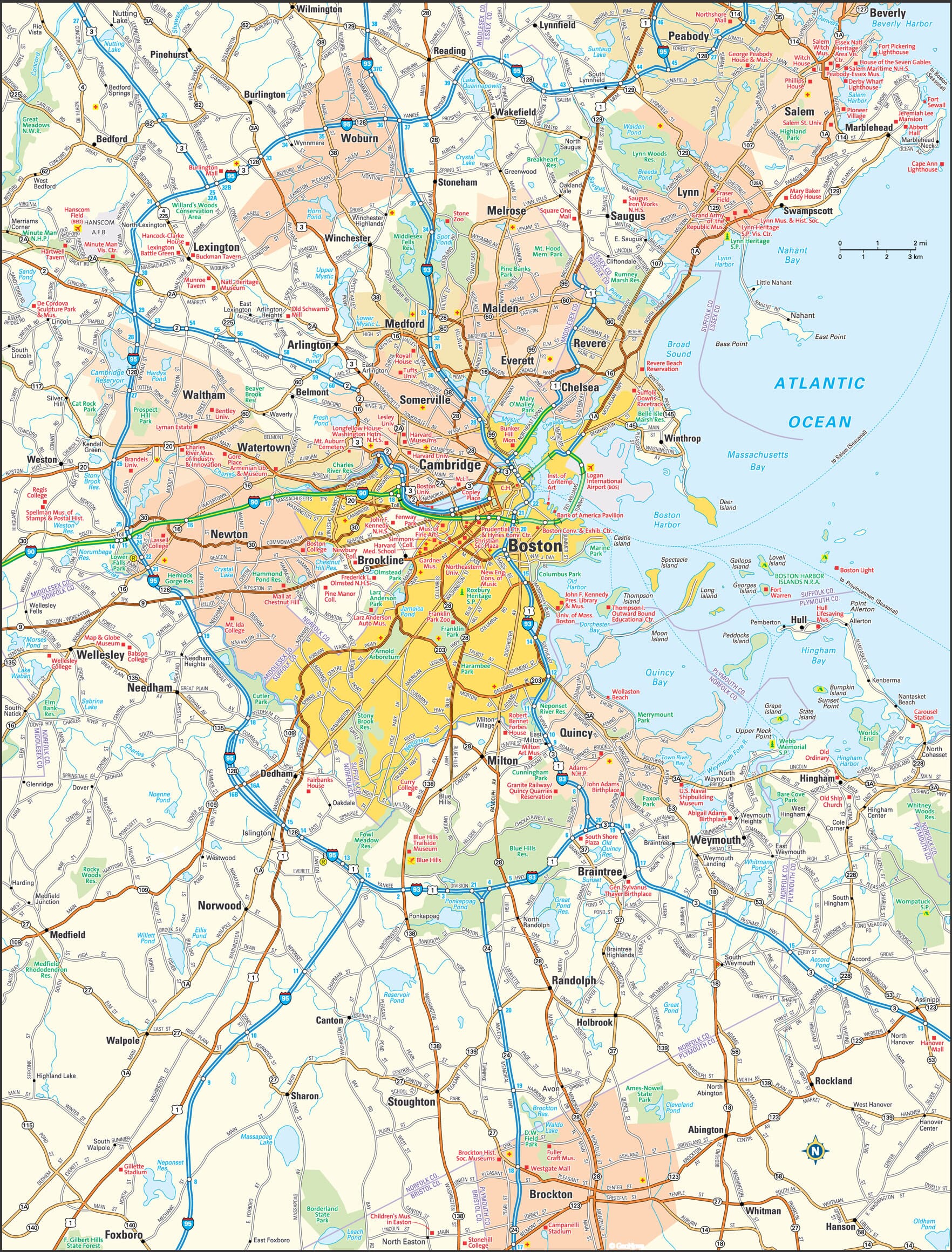

Boston sits at approximately 42.3 degrees North and 71.0 degrees West. If you’re scanning a physical map, follow the coastline up past New York and Connecticut. You’ll see the "arm" of Cape Cod jutting out into the ocean like a flexed bicep. Boston is nestled just north of that, right in the curve of Massachusetts Bay. It’s tight. It’s compact. And compared to the sprawling grids of Western cities like Phoenix or Denver, Boston on a map looks like a tangled ball of yarn.

Where Boston on a Map of the US Actually Sits

When people try to find Boston on a map of the US for the first time, they often underestimate how far north it really is. It isn't just "near" New York. It’s about 200 miles northeast of Manhattan. If you’re driving, that’s a four-hour slog on I-95, depending on how bad the traffic is around Providence or New Haven.

The city is the anchor of the New England region. To its north are New Hampshire and Maine. To its west, the rest of Massachusetts stretches out toward the Berkshires. But the geography is dominated by water. You have the Charles River snaking through, separating Boston from Cambridge. You have the Mystic River to the north. And then there's the Harbor, which is a massive, island-dotted expanse that once made this the most important port in the Western Hemisphere.

It’s small.

Really small.

The city proper only covers about 48 square miles. Compare that to Jacksonville, Florida, which is over 750 square miles, and you start to realize why Bostonians are so obsessed with "neighborhoods." On a map, the city looks like a series of puzzle pieces—Back Bay, Southie, the North End—crammed into a tiny peninsula.

📖 Related: The Philadelphia Mummers Parade: What Most People Get Wrong About New Year's Day

The Peninsula That Grew

One thing that confuses people looking at historical maps of Boston versus modern ones is how much the land has changed. Back in the 1630s, Boston was what they called the Shawmut Peninsula. It was basically a thin neck of land connected to the mainland by a strip of dirt so narrow it would frequently flood during high tide.

If you look at a map from 1775, the city looks like a tadpole.

Fast forward to today, and most of the Boston you see on a map is actually "made land." In the 19th century, they literally chopped down hills (like the top of Beacon Hill) and dumped the gravel into the marshes to create the Back Bay and the Seaport. When you’re walking down Commonwealth Avenue today, you’re technically walking on a swamp that was filled in with dirt brought in by trains from Needham. It was one of the largest public works projects in American history, and it completely redefined the city's silhouette.

The Strategic Importance of the Northeast Corridor

Why does the specific spot of Boston on a map of the US matter so much? It’s the gateway. Because it’s one of the closest major American ports to Europe, it became the primary landing point for ideas, people, and goods for centuries.

Logistically, Boston is part of the "Northeast Megalopolis." This is that massive, glowing streak of lights you see on satellite photos that runs from D.C. up through Baltimore, Philly, and New York. Boston is the northern terminus of this chain. This position makes it a hub for the "Acela Corridor," the only place in the United States where high-speed rail actually feels somewhat functional.

- Proximity to London: Boston is about 3,200 miles from London. That’s nearly 250 miles closer than New York City is.

- The Hub Concept: Locals call it "The Hub," short for "The Hub of the Solar System." It was a joke from Oliver Wendell Holmes in the 1800s, but the name stuck because, on a regional map, all roads—and influence—really do lead there.

- Education Density: If you zoom in on a map of Greater Boston, you’ll see an insane concentration of pins for universities. Harvard, MIT, Tufts, Boston College, BU. There are over 50 colleges in the metro area.

Navigating the "Spaghetti" Streets

If you try to use a map of Boston to navigate by car, you’re going to have a bad time.

Seriously.

Unlike most American cities that use a grid system (think Philadelphia or Chicago), Boston’s streets were largely built on top of old wandering footpaths and cow pastures. They follow the topography of the land rather than any logical plan. There is a famous legend that the streets were laid out by wandering cows, and while that’s technically a myth, when you're stuck on a one-way street in the North End that suddenly turns into a pedestrian alley, it feels 100% true.

How to Read a Boston Transit Map

Looking at the "T" map—the MBTA subway system—is often more useful for understanding the city than a topographical one. The T is the oldest subway in North America (opened in 1897). It’s color-coded: Red, Blue, Orange, and Green.

The Green Line is the weird one. It’s actually a light-rail trolley system that branches out into four different lines (B, C, D, and E). On a map, it looks like a vein splitting into capillaries. If you’re trying to get to Fenway Park or the Museum of Fine Arts, you’re looking at that Green Line sprawl. The Blue Line is the only one that goes under the harbor to the airport, which, on a map, looks surprisingly close to downtown but is separated by a deep channel of water.

The geography of the T explains the social geography of the city. The Red Line connects the intellectual powerhouses of Cambridge (Harvard/MIT) with the residential heart of Dorchester. The Orange Line cuts through the center, connecting the North Shore suburbs to the South Side.

The Weather Factor: Geography is Destiny

Boston's position on the map also explains why the weather is so schizophrenic. Because it sits right where the warm Gulf Stream meets the cold Labrador Current, the city gets hammered by "Nor'easters." These are massive storms that suck up moisture from the Atlantic and dump it as heavy, wet snow.

If Boston were just fifty miles inland, the weather would be more stable. But because it's right on the edge of the shelf, the "ocean effect" can mean the difference between a light rain in the city and two feet of snow just ten miles west in Waltham. When you look at a weather map of the US, you’ll often see a sharp line cutting right through Boston; that’s the "rain-snow line," and it’s the bane of every commuter's existence.

Surprising Map Details You Might Miss

- Logan Airport is practically in the water. On a map, it looks like a series of runways floating in the harbor. It’s actually built on several former islands that were connected by landfill.

- The "Lost" Mountains. Boston used to have three major peaks called the Trimount. They were leveled to fill in the bays. Only a tiny portion of Beacon Hill remains at its original height.

- The Harbor Islands. Most people don't realize there are 34 islands in Boston Harbor. Some have abandoned hospitals, others have Civil War-era forts (like Fort Warren on Georges Island). You can see them clearly on any decent nautical map.

Getting Your Bearings: A Practical Approach

If you’re actually trying to visit or understand the layout, start with the Common. The Boston Common is the oldest public park in the country, and on a map, it acts as the "center" of the city. From there, the city fans out.

- To the North: The North End (Italian district) and the TD Garden.

- To the West: The Back Bay (shopping on Newbury Street) and Fenway.

- To the South: The South End (brownstones) and South Boston (the waterfront).

- Across the Water: East Boston (the airport) and Charlestown (The USS Constitution).

If you can find the Common on a map, you can find anything else in the city by using it as your North Star.

Why Google Maps Struggles with Boston

Actually, even modern GPS has a hard time with Boston’s geography. Because of the "Big Dig"—a massive project that moved the elevated Central Artery highway into a series of tunnels underground—signal drops are common. On a map, you might look like you're on a surface street, but you're actually 80 feet underground in the Tip O'Neill Tunnel. It’s a 1.5-mile stretch of road that, for a decade, was the most expensive highway project in the world.

Moving Forward: How to Use This Information

If you are planning a trip or just trying to win a geography bee, keep these takeaways in mind. Boston isn't just a dot on the map; it’s a living, breathing example of how humans can force land out of the sea.

To get the most out of your "map study," do the following:

👉 See also: Stone Harbor Jersey Shore: What Most People Get Wrong About This Tiny Island

- Compare a 1700s map to a 2026 map. Use a tool like the Leventhal Map & Education Center’s digital archives. It will blow your mind to see how much of the city is artificial.

- Look at the "Nautical Charts" of the harbor. The depth of the water is why Boston became a shipping giant. The deep-water channels come right up to the city's edge.

- Track the "Emerald Necklace." This is a series of connected parks designed by Frederick Law Olmsted (the guy who did Central Park). On a map, it looks like a green ribbon winding through the city's "neck."

- Check the elevation maps. You’ll see why certain areas like the Seaport are at high risk for flooding as sea levels rise—they are basically at sea level because, well, they used to be the sea.

Understanding Boston on a map of the US requires looking past the coordinates. It’s about the relationship between the solid land of New England and the volatile Atlantic Ocean. Once you see that curve of the bay, you’ll never miss it again.