You’ve seen the photos. Those massive limestone pyramids poking through a sea of green jungle canopy, looking like something straight out of a movie. People go to Chichén Itzá, take the selfie, buy the overpriced magnet, and think they’ve "done" the Maya world. But if you actually look at mayan ruins on map displays from most travel blogs, you're only seeing about 5% of the story. Most of those maps are basically just pins on a highway.

The reality is way messier. And more exciting.

✨ Don't miss: Santa Fe New Mexico Time Zone Explained (Simply)

Archaeologists have been using LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) lately to strip away the jungle digitally. What they found changed everything. They didn’t just find a few more houses; they found tens of thousands of structures—highways, fortresses, and complex irrigation systems—that nobody knew existed. If you’re trying to find mayan ruins on map apps like Google Maps or even specialized GPS tools, you’re looking at a ghost of a civilization that was far more crowded than we ever imagined.

The big mistake everyone makes with the "Maya World" map

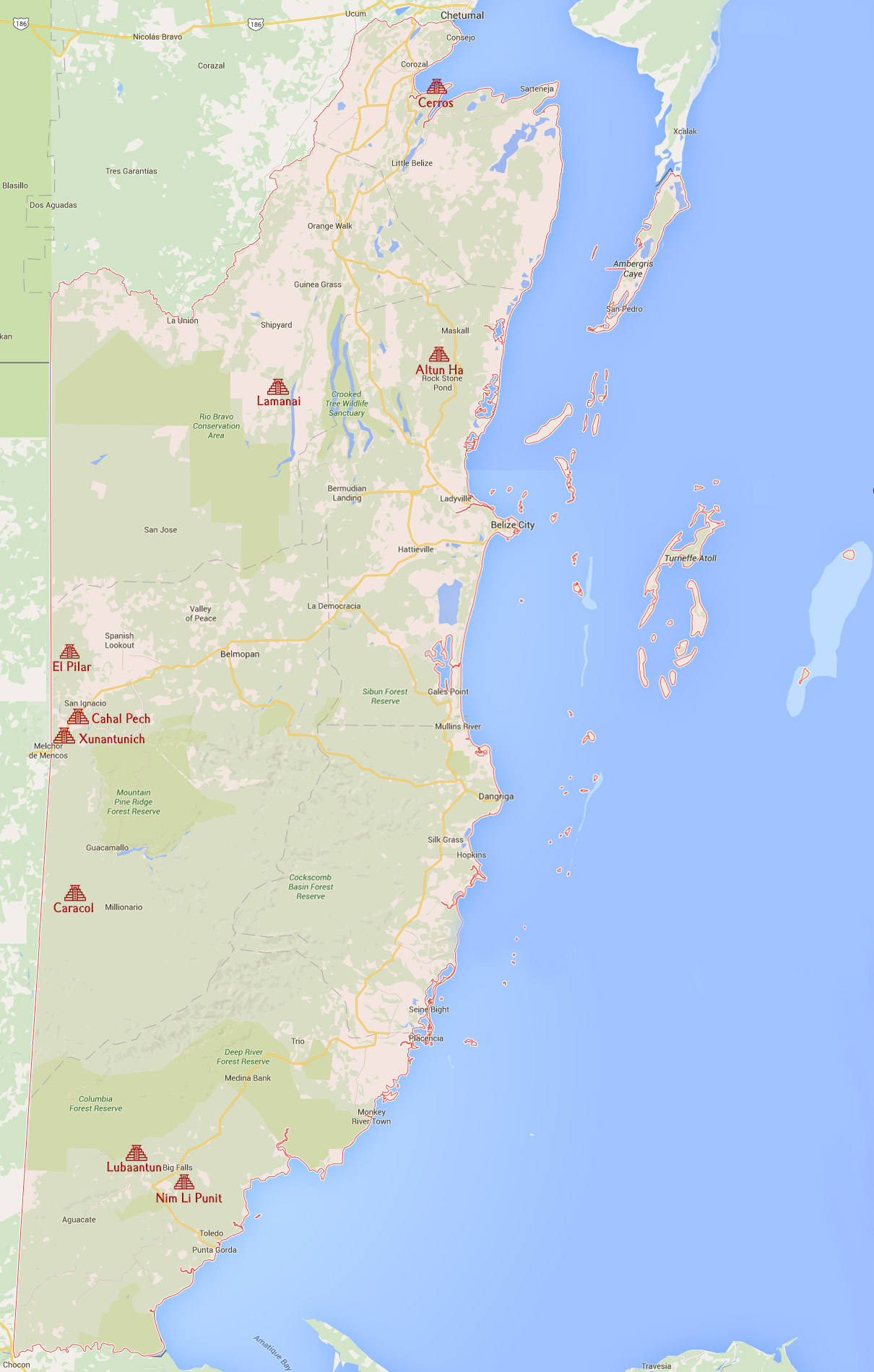

Most people think the Maya were one big empire like the Romans. They weren't. Honestly, they were more like the ancient Greeks—a bunch of city-states that spent as much time stabbing each other as they did trading. When you look at mayan ruins on map layouts across Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and Honduras, you have to understand the geography of power.

Take the Petén Basin in Guatemala. This is the heartland. If you zoom in on a map of this region, you'll see Tikal. It's the big one. The powerhouse. But just a bit north is El Mirador, a city that was actually bigger and older than Tikal, yet it’s barely a blip on most tourist maps because you have to trek through the mud for two days to get there.

The map is a lie because it prioritizes accessibility over importance.

We see the "Puuc" style ruins in the north of the Yucatán Peninsula, like Uxmal. These are stunning, covered in intricate stone mosaics. Then you have the "Chenes" style and the "Rio Bec" style further south. A map makes them look like neighbors. In reality, they represented totally different political eras and architectural philosophies. If you’re planning a trip based on a map, you might think you can "hit the highlights" in a week. You can't. The jungle doesn't care about your itinerary.

Why Lidar changed how we see mayan ruins on map views

Back in 2018, a massive breakthrough happened. The PACUNAM LiDAR Initiative surveyed over 2,000 square kilometers of the Guatemalan jungle. They used planes equipped with lasers to "see" through the trees.

What popped up on the screen? A massive interconnected web.

Specifically, they found elevated stone highways, called sacbeob. These weren't just paths; they were literal arteries of commerce and war. When you see mayan ruins on map markings today, most of those sacbeob aren't even drawn. But they are the most important part! They show us that the Maya weren't living in isolated jungle pockets. They were living in a massive, urbanized sprawl that looked more like modern-day Los Angeles than a collection of quiet temples.

It’s kinda wild to think about. We used to estimate the population at a few million. Now? Some experts, like Marcello Canuto from Tulane University, suggest it could have been up to 10 or 15 million people. All that, and we're still finding new stuff every single month.

The "Big Three" you'll find on any map (and why they're different)

If you open up any digital map and search for ruins, these three will dominate your screen. They are the heavy hitters for a reason.

🔗 Read more: Why the Coral Castle Museum in Florida Still Baffles Modern Engineers

Chichén Itzá: The Tourist Magnet

Located in Yucatán, Mexico. It’s the one with the El Castillo pyramid. This place is unique because it shows a "melting pot" of cultures. You see traditional Maya architecture mixed with Toltec influences from Central Mexico. It’s on every mayan ruins on map search because it’s easy to get to from Cancún. But here's a tip: it's crowded. If you don't get there at 8:00 AM, you’re basically walking through a theme park.

Tikal: The Jungle King

This is in Guatemala. If Chichén Itzá is the commercial hub, Tikal is the soul. The pyramids here are steep—really steep. Temple IV towers over the jungle at 230 feet. When you look at Tikal on a map, it looks isolated. When you’re there, you realize it was a superpower that fought a "World War" with its rival, Calakmul, for centuries.

Palenque: The Artist's Retreat

Tucked into the foothills of the Chiapas highlands in Mexico. Palenque isn't the biggest, but it’s the most elegant. The Temple of the Inscriptions held the tomb of Pakal the Great. His jade death mask is one of the most famous artifacts in history. On a map, Palenque looks like it’s on the edge of the world. Geographically, it was the gateway to the Usumacinta River trade routes.

The ruins that aren't on your "Average" map

If you really want to see the Maya world, you have to look for the "invisible" pins.

Have you ever heard of Caracol in Belize? It’s massive. In its prime, it was larger than modern-day Belize City. Yet, it gets a fraction of the visitors. Or how about Calakmul? It’s hidden deep in a biosphere reserve in Mexico, right near the Guatemalan border. Because it’s so hard to reach, it’s one of the few places where you can still see wild jaguars and spider monkeys while standing on top of a 150-foot pyramid.

When you search for mayan ruins on map locations, most people ignore the "Ruta Puuc." This is a string of smaller sites like Kabah and Sayil. They are masterpieces of stone carving. They’re basically ignored because they don't have the "Giant Pyramid" that looks good on Instagram. That’s a mistake. The detail at Kabah—where there are hundreds of masks of the rain god Chaac—is better than anything you'll see at the major sites.

Mapping the collapse: What actually happened?

The biggest question people ask when looking at these maps is: "Where did they go?"

It’s a trick question. They didn't "disappear." There are over 6 million Maya people living today in Mexico and Central America, speaking languages like Yucatec, Kʼicheʼ, and Qʼanjobʼal. But the cities did fail.

👉 See also: Sing Sing Ave A: Why This Historic Ossining Neighborhood Is Still Relevant

If you look at a mayan ruins on map chronological progression, you see a shift. The "Classic" period cities in the southern lowlands (like Tikal) started failing around 800-900 AD. The map "moves" north. People migrated. They went to the Yucatán coast. They went to the highlands.

Why? It wasn't just one thing. It was a perfect storm.

- Climate Change: Severe, multi-decadal droughts hit the region.

- Deforestation: They needed massive amounts of wood to burn limestone for plaster. No trees = no topsoil = no food.

- Endless War: The rivalry between Tikal and Calakmul drained resources and lives.

- Social Unrest: Eventually, the commoners likely just got tired of building giant monuments for kings who couldn't make it rain.

How to use a map to actually visit these sites

Don't just trust a generic GPS pin. Many of these sites are deep in jungle territory with no cell service.

If you’re serious about exploring, you need a multi-layered approach. Start with the Maya Train (Tren Maya) map if you’re in Mexico. It’s controversial, but it’s making sites like Edzná and Palenque way more accessible. Just be aware that "accessible" usually means "more crowded."

For the real adventurer, look at the "Three Rivers" region of Belize or the Petexbatún region of Guatemala. You’ll need a local guide. You’ll need a 4x4. Honestly, you'll probably need bug spray with a terrifying amount of DEET.

Actionable steps for your Maya exploration

You want to see the Maya world for real? Stop looking at the top 10 lists and do this:

- Download Offline Maps: Google Maps will fail you in the Petén jungle. Use apps like Maps.me or Gaia GPS and download the entire region before you leave your hotel.

- Check the Elevation: If a site is in the highlands (like Iximche in Guatemala), it’s going to be chilly. If it’s in the lowlands (like Quiriguá), the humidity will melt you. Use a topographic map, not just a flat road map.

- Follow the Lidar News: Sites like National Geographic and the Journal of Field Archaeology post the newest "discoveries." Sometimes these sites aren't even open to the public yet, but knowing where they are helps you understand the "empty" spaces on the map aren't actually empty.

- Prioritize the "Secondary" Sites: Use your map to find sites within 30 miles of the big ones. For example, if you go to Palenque, make sure to hit Bonampak and Yaxchilán. You have to take a boat down a river to get to Yaxchilán. It’s an incredible experience that 99% of tourists miss because they didn't look closely enough at the map.

- Understand the "Sacbe": When you are at a site, look for the straight, raised white roads. These were the literal connections on the ancient mayan ruins on map of the past. Following a sacbe often leads you to smaller, unrestored groups of buildings where you can have a moment of actual silence.

The Maya world is a giant puzzle. We’ve only found about half the pieces. Every time someone looks at a map and decides to go a little further down a dirt road, we learn something new. Don't just follow the pins. Look for the gaps between them. That’s where the real history is hiding.