Look at a globe. Your eyes probably drift toward that massive green smudge in South America. Most people, when they try finding the Amazon River on a map, just point their finger at Brazil and call it a day. They aren't technically wrong, but they're missing about eighty percent of the story. The Amazon isn't just a line on a page; it’s a living, shifting circulatory system that basically breathes for the entire planet.

It’s huge. Honestly, the scale is hard to wrap your head around.

🔗 Read more: Finding Your Way: What Most People Get Wrong About a Map of the French Quarter in New Orleans Louisiana

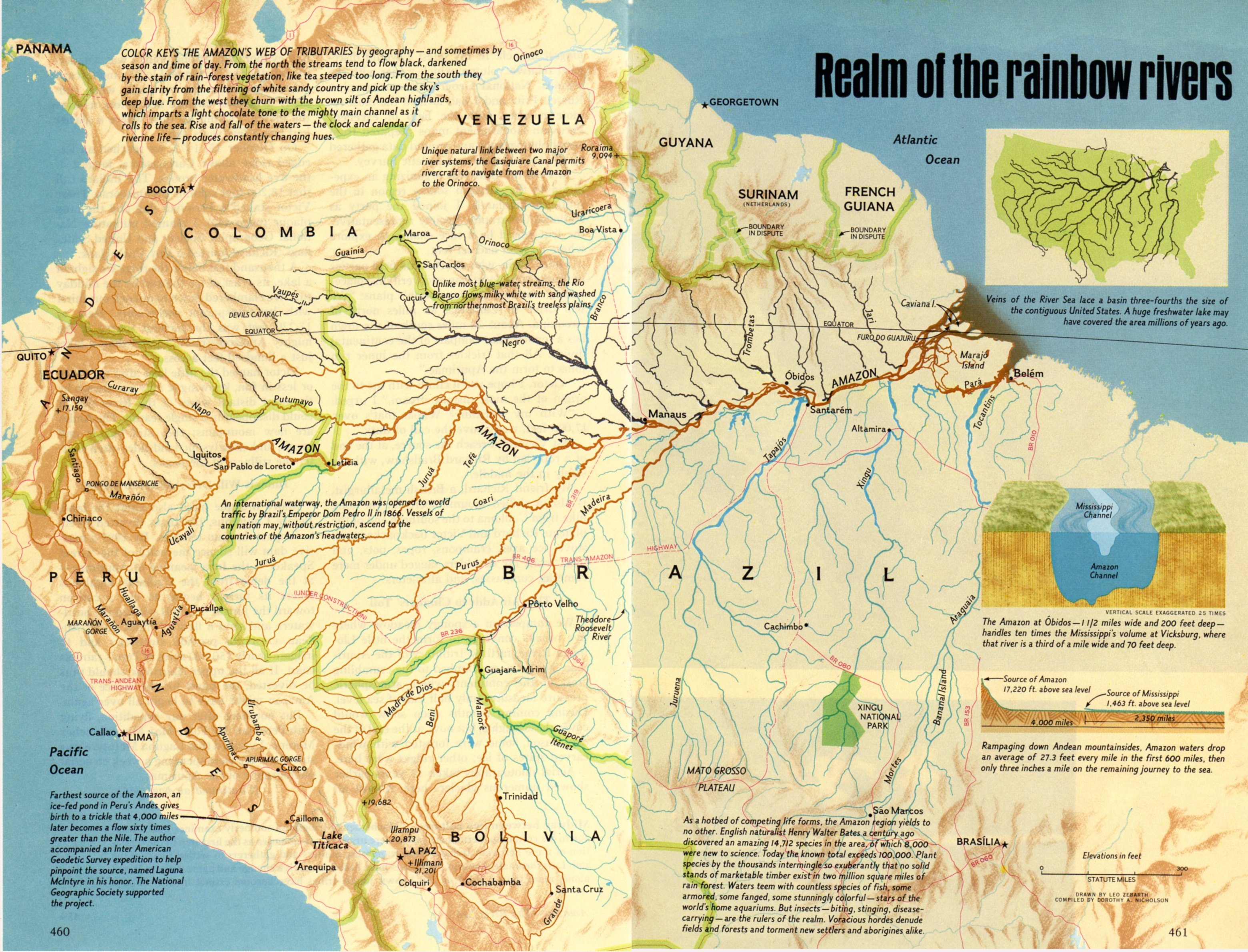

If you’re looking for the start of it, don't look in the jungle. Look at the clouds. Or rather, look at where the clouds hit the jagged, frozen peaks of the Andes Mountains in Peru. For decades, geographers fought over the "true" source. Was it the Marañón? The Ucayali? In 2014, researcher James Contos and his team used GPS tracking and satellite data to argue that the Mantaro River is the most distant source. If you’re tracing the Amazon on a map today, you start high up in the Peruvian highlands, nearly 16,000 feet above sea level, before the water even thinks about entering the rainforest.

Where is the Amazon River on a Map? Navigating the "River Sea"

To find it, start your finger on the west coast of South America, just a stone's throw from the Pacific Ocean. That’s the irony. The river starts almost at the Pacific but decides to trek 4,000 miles across the entire continent to dump into the Atlantic.

It cuts a horizontal path across the top third of South America. While Brazil owns the lion's share, the basin bleeds into Peru, Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia, and even touches parts of Venezuela, Guyana, and Suriname. It’s not a single pipe. Think of it more like a giant, messy tree with thousands of branches. Some of those "branches," like the Rio Negro or the Madeira, are actually larger than most of the famous rivers in Europe or North America.

The Brazilian Heartland

Once the mountain streams merge, they hit the lowlands. This is the classic "Amazon" you see in National Geographic. The river flows past Iquitos in Peru—the largest city in the world unreachable by road—and crosses into Brazil at a border town called Tabatinga. From there, it becomes the Solimões until it hits Manaus.

Manaus is a weird place. It’s a massive industrial city of two million people dropped right in the middle of the deep green. This is where the "Meeting of Waters" happens. You can see it on satellite maps as a distinct line where the black-tea-colored Rio Negro hits the sandy, tan Solimões. They run side-by-side without mixing for miles because they have different speeds and temperatures. It looks like a giant cup of coffee that someone forgot to stir.

Reaching the Atlantic

Eventually, the river reaches the Marajó Island area near Belém. This is the finish line. The mouth of the Amazon is so wide—roughly 150 miles across—that early explorers called it the Mar Dulce, or the Freshwater Sea. It pumps about 209,000 cubic meters of water into the ocean every single second. That’s more than the next seven largest rivers combined. If you poured that into a map of the United States, it would submerge the entire country in several feet of water in no time.

Why the Map Keeps Changing

Maps are usually static, but the Amazon is anything but. The river is a master of "meandering." Because the terrain is so flat—the river only drops about 200 feet in its final 2,000 miles—the water moves sluggishly and carves out massive loops.

Sometimes, the river gets tired of the loop. It cuts across the neck of a bend, leaving behind a crescent-shaped lake called an oxbow lake. If you look at a high-resolution satellite map of the Amazon basin, it looks like it’s covered in scars. Those are all the places the river used to be.

🔗 Read more: The Real Experience at Bullets and Burgers Las Vegas Rides and Attractions

Climate change is making this even messier. In 2023 and 2024, the Amazon faced record-breaking droughts. Tributaries that usually carry massive cargo ships turned into dust bowls and mud pits. People were walking where they used to boat. When you look at a map of the Amazon today, you have to realize that the blue lines are seasonal suggestions, not permanent boundaries.

Practical Tips for Digital Map Users

If you're using Google Maps or Earth to find the river, don't just search for "Amazon River." You’ll just get a pin in the middle of the forest.

Instead, try these coordinates: -3.149, -59.904. That’ll put you right over the Meeting of Waters near Manaus. Switch to "Satellite View." You’ll see the color contrast immediately.

Zoom out. Look at the surrounding green. Notice the "fishbone" patterns. Those aren't natural. Those are roads being cut into the forest, usually followed by farming and cattle ranching. Mapping the Amazon isn't just about finding water; it’s about tracking the loss of the canopy.

Essential Landmarks for Your Search

- The Source: Look for Nevado Mismi in Peru. It’s a jagged peak that was long considered the "official" start.

- The Triple Frontier: Find the spot where Peru, Brazil, and Colombia meet. It’s a hub of river culture.

- The Delta: Find Marajó Island. It’s an island the size of Switzerland sitting right in the mouth of the river.

The Reality of Mapping the Rainforest

Honestly, we still don't know everything about what's under that canopy. LIDAR technology—which uses lasers to "see" through trees—is currently uncovering lost cities and massive earthworks that don't show up on standard maps. Archeologists like Eduardo Neves have been finding evidence that the Amazon wasn't a pristine wilderness, but a heavily "managed" landscape by indigenous populations for thousands of years.

So, when you're looking for the Amazon River on a map, you're looking at a graveyard of ancient civilizations, a modern economic highway, and a biological engine all at once.

To get the most out of your geographical exploration, start by downloading an offline map of the Amazonas region in Brazil or the Loreto region in Peru. Use tools like Global Forest Watch to overlay the river’s path with recent deforestation data. This gives you a "living map" perspective rather than a flat, 2D view. If you're planning a physical trip, remember that the river rises and falls by up to 30 or 40 feet depending on the season, so the "shoreline" you see on your phone might be underwater or a mile away by the time you arrive.