Ever tried to track a tom in the brush? It's honestly a nightmare if you don't know what you're doing. You see a flash of red or a shimmer of bronze and—poof—he’s gone. If you are looking for wild turkey pictures male hunters and birders actually respect, you have to understand the strut. Most people just snap a blurry photo of a bird running away. That isn't what we want. We want the full display. The "Meleagris gallopavo" in all its ridiculous, over-the-top glory.

Capturing a high-quality image of a male wild turkey—often called a tom or a gobbler—requires more than just a decent lens. It takes a weird mix of patience, camouflage, and understanding avian psychology. These birds have eyesight that makes a hawk look like it needs glasses. If you blink wrong, they're gone.

The Anatomy of a Perfect Male Turkey Photo

When you're scrolling through wild turkey pictures male enthusiasts post online, the ones that stand out always feature the "Full Strut." This isn't just a pose; it's a biological flex. The tail feathers fan out into a perfect semi-circle. The wings drop and drag against the ground, making a "scritch-scritch" sound that you can actually hear if you're close enough.

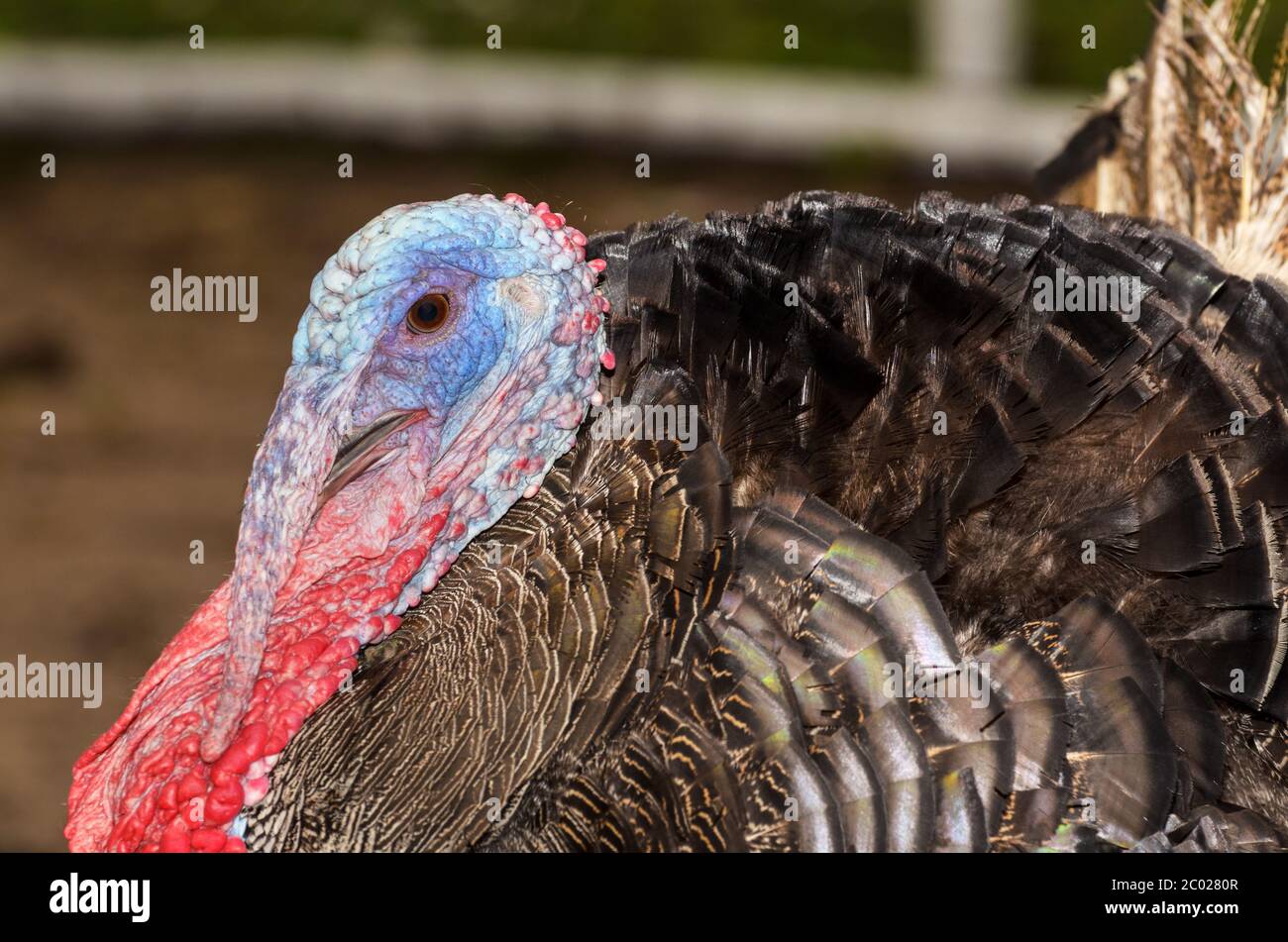

But look closer at the head.

A tom’s head can change color based on its mood. Seriously. When a male is excited or aggressive, its head can turn a vivid, patriotic mix of red, white, and blue. The fleshy bit hanging over the beak is called a snood. When they're relaxed, it's short. When they're looking for a mate or trying to intimidate a rival, it elongates. Getting a photo where the snood is draped long and the caruncles (those bumpy bits on the neck) are bright red is the "gold standard" for wildlife photography.

Why lighting ruins most shots

Turkeys are basically walking prisms. Their feathers are iridescent. If you take a picture in the flat light of high noon, the bird just looks like a dark, dusty brown blob. It's boring. But get that same bird in the "Golden Hour"—that first hour of light after sunrise—and everything changes. The feathers shimmer with copper, gold, and green.

I’ve seen photographers spend six hours in a blind just for three minutes of the right light hitting a tom's breast feathers. It’s the difference between a "snapshot" and a "photograph." If you aren't shooting with the sun at your back, you're likely going to underexpose the bird, losing all that incredible texture in the plumage.

Behavioral Cues You Can't Ignore

You can't just walk up to these guys. You've gotta be a ghost. Wild turkeys are incredibly skittish. Unlike the ones in a petting zoo, wild toms have spent their entire lives making sure things don't eat them.

- The "Spit and Drum": Before a tom struts, he makes a low-frequency sound. It’s a sharp "pfft" followed by a low hum. If you hear this, stop moving. He’s about to blow up like a beach ball.

- The Periscope: If a turkey stands tall and stretches its neck, it has spotted something. You. If you see this in your viewfinder, don't even breathe. If you move your camera now, he’s taking flight.

- The Gobble: Obviously, this is the iconic sound. But for a photographer, the gobble is a vibration. When they belt one out, their whole body shakes. It’s a great moment for a "dynamic" shot, but you need a high shutter speed—at least 1/1000th of a second—to freeze that motion. Otherwise, the head will just be a red blur.

Honestly, the best wild turkey pictures male birds offer are often the ones where they are interacting with other toms. Seeing two males "facing off" with their chests pressed together is a rare and aggressive display that looks incredible on a high-res sensor.

Gear Matters (But Technique Matters More)

You don't need a $10,000 rig, but you do need reach. A 300mm lens is the bare minimum. A 500mm or 600mm is better.

But here is the secret: get low.

Most people take pictures from eye level. It looks like a human looking down at a bird. Boring. If you get down on your stomach—yes, in the dirt—and shoot from the turkey's eye level, the perspective shifts. Suddenly, the bird looks massive and majestic. The background blurs into a creamy "bokeh," making the subject pop.

National Geographic photographer Joel Sartore often emphasizes the importance of the eyes in animal portraiture. If the eye isn't in sharp focus, the picture is trash. For turkeys, this is tricky because their heads move constantly. Using "Eye-AF" (Auto Focus) technology found in modern mirrorless cameras from Sony, Canon, or Nikon is a total game-changer here.

🔗 Read more: Where to Find Chia Seeds at WinCo Without Overpaying

The Camouflage Fallacy

You don't necessarily need a full Ghillie suit, although it helps. What you actually need is to break up your silhouette. Turkeys see movement and shapes. Sitting against a wide tree trunk that is wider than your shoulders is often enough.

Also, watch your hands and face. Pale skin stands out like a neon sign in the woods. Wear gloves and a face mask. It sounds extreme just for a photo, but these birds are the ultimate "spot the difference" players.

Common Mistakes When Cataloging Wild Turkey Pictures Male

I see a lot of people misidentify "jakes" as mature toms. If you want your photography to be taken seriously by the birding community or groups like the National Wild Turkey Federation (NWTF), you have to know the difference.

A "jake" is a juvenile male. How can you tell from a photo? Look at the tail fan. In a mature tom, all the feathers in the fan are the same length, creating a smooth arc. In a jake, the middle feathers are longer than the ones on the sides. It looks uneven. Also, look at the beard—the tuft of hair-like feathers on the chest. On a jake, it's usually only two or three inches long. On a big old "boss gobbler," that beard can drag the ground, sometimes reaching 10 or 12 inches.

Another thing: don't over-process.

It’s tempting to crank the saturation to make those red heads look like fire. Don't. It looks fake. Digital sensors struggle with "red channel clipping." If you push the red too hard in Lightroom or Photoshop, you lose all the detail in the caruncles, and it just looks like a red blob of digital ink. Keep it natural.

Where to Find Them (Real Locations)

You can't take wild turkey pictures male birds inhabit if you're looking in the wrong habitat. They love "edge" habitat. Think of where a forest meets a field. They sleep in the big hardwoods at night and fly down to the fields at dawn to feed and strut.

- Cades Cove, Tennessee: This is basically a turkey photography zoo. The birds in Great Smoky Mountains National Park are somewhat habituated to cars, meaning you can get stunning shots from the roadside.

- Land Between the Lakes, Kentucky/Tennessee: Massive populations and open woodlots make for great visibility.

- The Black Hills, South Dakota: Here you find the Merriam’s subspecies. These are gorgeous because the tips of their tail feathers are creamy white instead of the buff-brown found on Eastern turkeys. They look incredible against a dark evergreen background.

Actionable Steps for Your Next Outing

If you're serious about getting that "wall-hanger" shot, follow this workflow.

First, scout. Don't even bring the camera. Just go out at sunset and listen for where they "put to bed" (fly up into trees). They'll likely be in the same area the next morning.

🔗 Read more: How Pope John Paul II Education Shaped the Modern World

Second, get there early. If the sun rises at 6:30 AM, you should be sitting against your tree by 5:45 AM. Total silence.

Third, use a tripod or a monopod. When a tom starts coming in, you might be holding that camera up for 15 minutes waiting for him to turn into the light. Your arms will shake. A support system is non-negotiable for sharp images.

Finally, shoot in bursts. Turkeys blink. They jerk their heads. They snap at bugs. Taking a single frame is a gamble. Shooting a 5-frame burst gives you a much better chance of catching that perfect moment when the eye is open and the light hits the snood just right.

When you finally get that shot—the one where the iridescent feathers look like a wet oil painting and the tom's gaze is fixed right on you—you'll realize why people obsess over these birds. It’s not just a picture; it’s a trophy of a very difficult hunt where the only thing you took was a memory and a RAW file.

Start by checking your local state park regulations, as many allow photography year-round even when hunting seasons are closed. Focus on the Eastern subspecies for classic colors, or head west for the striking white-tipped Merriam’s if you want something unique for your portfolio. Use a wide aperture like f/4 or f/5.6 to separate the bird from the messy forest background. This simple setting change instantly upgrades your work from a "bird in the woods" to a professional-grade wildlife portrait.