If you look at South America from a satellite perspective, you might expect the whole continent to be a flat, green carpet of Amazonian rainforest. It isn't. Not even close. When you're trying to locate the brazilian highlands on map, you’re actually looking for a massive, rugged triangle of ancient rock that occupies nearly half of Brazil's total landmass. It’s huge. Honestly, the scale is hard to wrap your head around until you realize this region is technically larger than most European countries combined.

The Highlands, or Planalto Brasileiro, aren't just one big hill. They’re a complex, eroded mess of plateaus, mountain ranges, and deep river valleys. Geologically, we’re talking about some of the oldest crust on the planet. This isn't the pointy, dramatic peak style of the Andes. These are old mountains. They’ve been worn down by millions of years of rain and wind, resulting in those iconic "tabletop" mountains you see in photos of Chapada Diamantina.

Where to Spot the Brazilian Highlands on Map

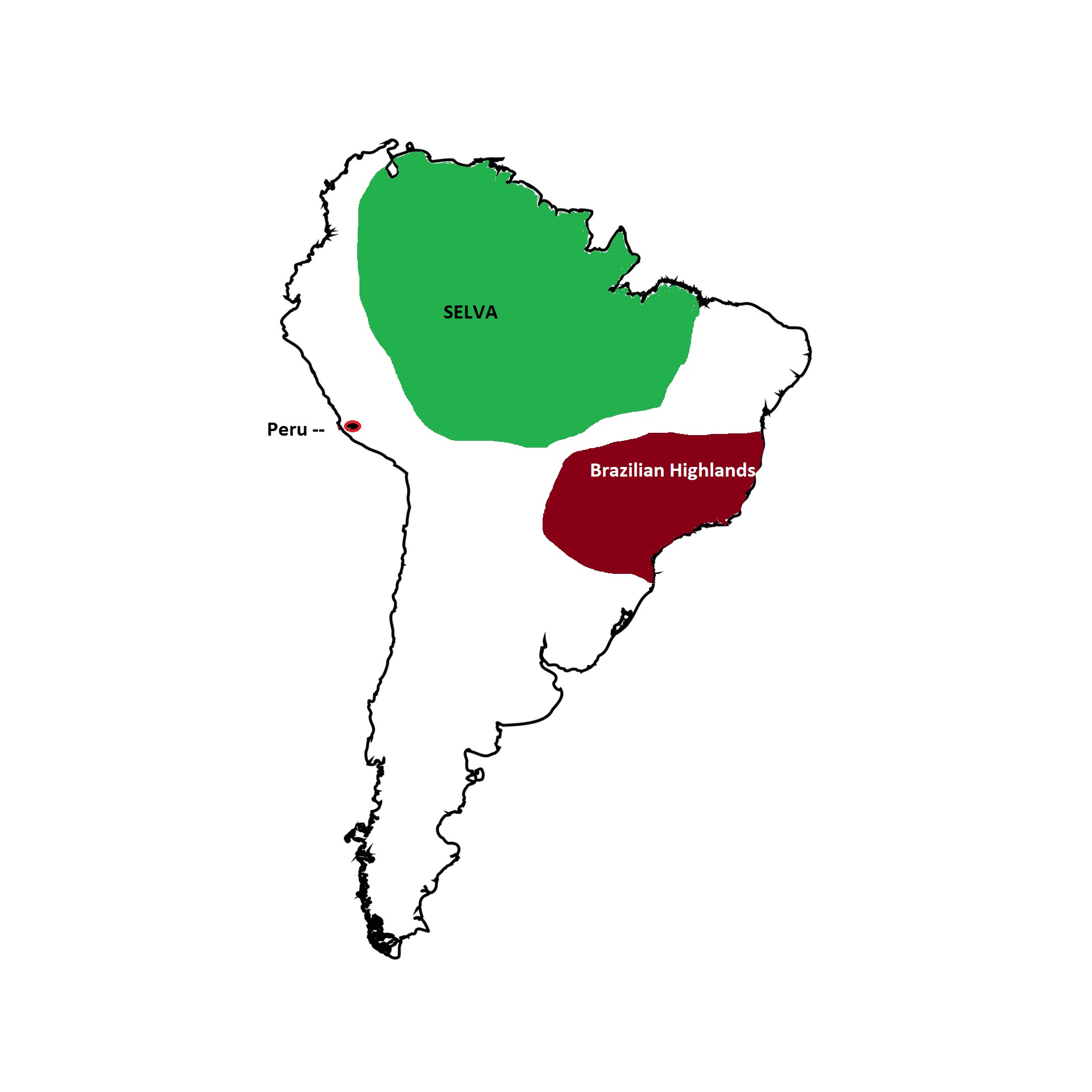

Basically, start your eyes at the Atlantic coast and move inward. The Highlands cover the eastern, southern, and central parts of Brazil. If you’re looking at a physical map, you’ll see a sea of orange and brown shades south of the Amazon Basin. That’s it. That’s the "Planalto."

It starts roughly near the city of Salvador and stretches all the way down toward the borders of Uruguay and Argentina. To the west, it hits the Pantanal—the world's largest tropical wetland. To the north, it drops off into the humid lowlands of the Amazon. It’s like a giant, tilted stone shield.

Most people get confused because the Highlands are split into three main parts:

- The Atlantic Plateau: This is the rugged stuff along the coast. It’s why Rio de Janeiro has those crazy granite peaks like Sugarloaf.

- The Central Plateau: This is the heart of the country. It’s flatter, higher, and where the capital, Brasília, sits.

- The Southern Plateau: This is where things get chilly. It’s characterized by volcanic rocks and lush forests of Araucaria pines.

Why the Geography is Actually Kind of Weird

The brazilian highlands on map don't follow the rules you'd expect. Most mountain ranges are formed by plates smashing together. The Highlands are more about what’s left over after everything else eroded away.

Because of this elevation, the climate in the Highlands is totally different from the steaming jungles people associate with Brazil. In places like São Joaquim or Urubici in the south, it actually snows. Seriously. Brazilians flock there in July just to see a dusting of white on the ground. It’s a complete 180 from the 40°C heat of Rio or Manaus.

The soil here is also legendary, but not always in a good way. In the Central Plateau, the soil is naturally very acidic. For decades, people thought you couldn't grow anything there. Then, in the 1970s, agricultural scientists realized that if you just dump massive amounts of lime (calcium carbonate) on the dirt, it becomes incredibly fertile. Now, this region—known as the Cerrado—is one of the biggest breadbaskets on Earth. It’s where a huge chunk of the world’s soy and beef comes from.

The Great Escarpment: A Massive Wall

If you’ve ever driven from São Paulo down to the coast, you’ve experienced the Great Escarpment. It’s essentially the "edge" of the Highlands.

Think of it as a giant wall.

The transition is jarring. You’re driving along a high, flat plateau at 800 meters, and suddenly the earth just falls away. The road starts snaking down through dense, misty Atlantic Forest. This wall is the reason why it took so long for the interior of Brazil to be developed. It was a nightmare for early explorers to haul equipment up that cliff. Even today, the engineering required to maintain highways and railways over the Escarpment is mind-boggling.

Biodiversity You Won't Find in the Rainforest

Everyone talks about the Amazon. It’s the superstar. But the brazilian highlands on map host the Cerrado and the Atlantic Forest, two of the most threatened hotspots on the planet.

The Cerrado is an "inverted forest." Because the region goes through long dry spells, the trees have evolved to have massive root systems that go deep underground to find water. There’s a saying that the Cerrado is a forest standing on its head. You might see a scrubby, three-meter tree, but its roots might go down twenty meters.

And the animals? They're weird and wonderful.

- The Maned Wolf: It looks like a fox on stilts. Those long legs are an evolutionary trick to help it see over the tall grasses of the highlands.

- Giant Anteaters: These guys roam the plateaus looking for termite mounds that are often as hard as concrete.

- Jaguar: While they love the wetlands, they are the undisputed kings of the highland canyons too.

The Economic Engine

It’s not just about nature. The Highlands are where Brazil’s money is. The "Golden Triangle" of São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Belo Horizonte all sit within or on the edge of this elevated region.

Belo Horizonte, in particular, is the gateway to the "Iron Quadrangle." This part of the highlands is packed with some of the highest-grade iron ore in the world. If you look at a satellite map of the area around Minas Gerais, you’ll see massive red scars in the earth. Those are mines. That iron is shipped all over the world to make the steel for skyscrapers in China and cars in Europe.

Also, coffee.

Coffee plants love the elevation and the volcanic soil of the Southern and Central Highlands. If you’re drinking a latte right now, there’s a statistically high chance the beans were grown on a hillside somewhere in the Brazilian Highlands. The altitude provides the perfect temperature range—warm days and cool nights—that gives the beans their flavor profile.

The "Water Tower" of South America

This is probably the most important thing nobody realizes about the brazilian highlands on map. This region acts as a giant water tower for the entire continent.

✨ Don't miss: Flights From Seattle to Albany New York: What Most People Get Wrong

Most of South America’s major river systems—excluding those that start in the Andes—begin in these highlands. The São Francisco River, the Paraná, and the Tocantins all have their headwaters here. These rivers flow out in every direction, providing water for irrigation, drinking, and, most importantly, electricity.

Brazil gets something like 60-70% of its electricity from hydropower. Most of those dams are built on the steep drops where highland rivers tumble toward the sea or the lowlands. Without this specific topography, Brazil would be a very different, and much darker, place.

Why Humans Changed the Map

For centuries, the Highlands were the "backcountry." That changed in 1960. The Brazilian government decided to move the capital from the coast (Rio) to the middle of nowhere in the Central Plateau. They built Brasília.

The goal was to "march to the west" and force development into the interior. Looking at the brazilian highlands on map today, you can see the result: a massive network of highways fanning out from the center. It transformed the Highlands from a sleepy land of cattle ranchers into a high-tech agricultural and political hub.

However, this came at a cost. The Cerrado is disappearing faster than the Amazon. Because it’s not as "pretty" or "iconic" as the rainforest, people don't fight as hard to save it. We’ve lost about half of the original vegetation in the highlands to soy plantations and cattle pastures. It’s a delicate balance between being a global food superpower and losing a biome that exists nowhere else.

Real Insights for Travelers and Geographers

If you’re planning to visit or study the region, don't treat it as a monolith.

🔗 Read more: Finding the Best Spots: Where to Stay for Holland Tulip Festival Without the Stress

The weather is the biggest variable. In the northern highlands (near the equator), it’s tropical and dry. In the south, it’s temperate. If you go to the Serra da Mantiqueira near São Paulo in June, bring a heavy coat. You’ll be at 2,000 meters above sea level, and the wind bitingly cold.

Practical Steps for Identifying Features

- Check the Shading: On a physical map, look for the "Craton"—the stable, ancient heart of the continent. It’s usually marked in dark oranges.

- Follow the Rivers: Trace the Paraná or the São Francisco upstream. Where they start to twist and turn through narrow valleys, you’ve hit the Highlands.

- Identify the "Chapadas": These are the high plateaus with flat tops. Chapada dos Veadeiros and Chapada Diamantina are the two big ones. They are easily visible on high-resolution topographical maps as distinct, raised blocks.

- Look for the Great Escarpment: Look at the coastline between Porto Alegre and Salvador. The very narrow coastal plain immediately gives way to steep green mountains. That’s the "wall" of the plateau.

The brazilian highlands on map represent the old soul of South America. While the Andes are the young, flashy upstarts of the west, the Highlands are the steady, ancient foundation of the east. They dictate where the water flows, where the coffee grows, and where the people live. Understanding this geography is the only way to actually understand Brazil beyond the beach.

To get a better sense of the scale, use a 3D topographic viewer. Focus on the state of Minas Gerais. The "wrinkles" you see there are some of the most mineral-rich mountains on earth. From there, pan west toward Brasília to see how the terrain levels out into the massive, high-altitude plains that feed a huge portion of the global population. This is a working landscape, a geological relic, and a biological treasure all at once. Study the elevation lines closely; the 500-meter contour map is usually the best way to see exactly where the Highlands begin and the lowlands end.