History is messy. If you look at a modern donner party trail map, you’ll see a clean, thin line snaking across the Sierra Nevada. It looks deliberate. It looks like a plan. But for the 81 souls trapped in the snow during the winter of 1846-1847, there was no line. There was just mud, exhaustion, and a series of catastrophic navigational gambles that turned a standard migration into a nightmare.

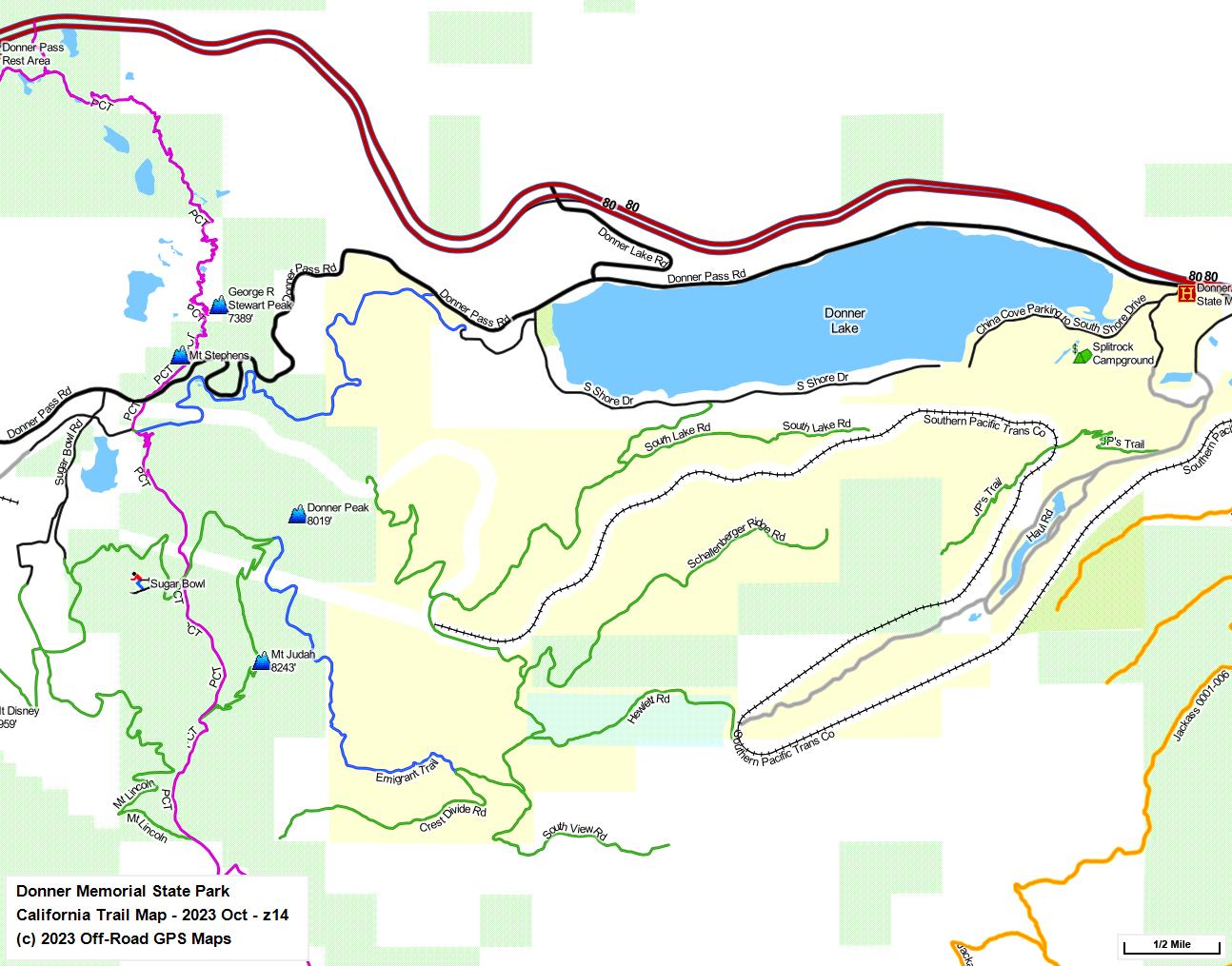

Most people think they know the story. Cannibalism. Snow. Desperation. Yet, if you actually stand at Donner Memorial State Park today, the geography tells a much more complex story than the sensationalized version we learned in grade school. The map isn't just about where they went; it’s about where they got lost.

The Fatal Detour: Understanding the Hastings Cutoff

The most critical part of any donner party trail map isn't the Sierra Nevada—it's the massive loop south of the Great Salt Lake. This was the "Hastings Cutoff."

💡 You might also like: Fort Pierce Weather: What Locals Know That Your iPhone App Doesn’t Tell You

Lansford Hastings was a guy with a dream and a very poorly researched guidebook. He promised a shortcut that would shave 300 miles off the journey to California. He'd never actually traveled the full route himself before promoting it. That's a wild thought. Imagine following a GPS route today created by someone who just looked at a satellite image and said, "Yeah, that looks flat enough."

The Donner-Reed party took the bait.

Instead of staying on the established Oregon Trail, they turned left at Fort Bridger. This is where the map gets ugly. The "shortcut" ended up being 125 miles longer than the established route. They weren't just moving slow; they were hacking a road through the Wasatch Mountains where no road existed. Every mile gained was paid for in dead oxen and broken spirits. By the time they reached the edge of the Great Salt Lake Desert, they were already weeks behind schedule.

The desert was supposed to take two days to cross. It took six.

Reading the Terrain at Truckee Lake

When you look at a topographic donner party trail map, you see a bottleneck. This is the infamous Donner Pass. By the time the group reached the base of the pass in late October, they were physically spent.

Then the weather turned.

It didn't just snow. It dumped. We’re talking about a series of storms that piled snow 20 feet high. If you go to the Breen Cabin site or the Murphy Cabin site today, you can see the massive boulders that served as the back walls for their makeshift shelters.

Actually seeing the proximity of the camps is chilling. The camps weren't all in one spot. The Breen, Graves, and Reed families were near what is now called Donner Lake (then Truckee Lake). The Donner family itself—George and Jacob and their kin—were stuck six miles back at Alder Creek.

Six miles.

In a modern car, that’s a ten-minute drive. In twenty feet of powder with no food and hypothermia, it might as well have been the moon. They were separated. Isolated. This lack of physical unity on the map played a massive role in the breakdown of the group's social structure.

Why the Map Doesn't Show the "Forlorn Hope"

In December, a group of fifteen refugees decided to make a break for it. They called themselves the "Forlorn Hope." They had makeshift snowshoes and almost zero rations.

💡 You might also like: Places to stay near Letchworth State Park: What Most People Get Wrong

Mapping their route is nearly impossible because they were wandering blindly through the rugged canyons of the North Fork of the American River. They weren't on a trail. They were dying. Of the fifteen who left, only seven survived to reach the settlements in California. Their path is a jagged zig-zag of desperation that bypasses every logic of modern trail blazing.

Modern Landmarks on the Donner Party Trail Map

If you’re planning to visit these sites, don’t just rely on a digital pin. The geography has changed, but the bones of the trail are still there.

- Donner Memorial State Park: This is the "easy" part. The Pioneer Monument stands exactly as high as the snow reached that winter—22 feet. It’s a sobering visual.

- Alder Creek: Located a few miles north of the main park. This is where the Donners stayed in "tents" made of quilts and brush because they couldn't reach the lake before the snow hit. It feels much more lonely here than at the main lake.

- The Big Bend: Further down the mountain. This is where rescue parties struggled to move upward.

You've got to realize that the Emigrant Trail wasn't a highway. It was a series of braided paths. Depending on the mud, the forage for the cattle, or the broken axles, the "trail" could be a mile wide.

The Logistics of a Failed Migration

We often focus on the tragedy, but the donner party trail map is also a map of logistics. A wagon train is essentially a moving city. It requires thousands of calories a day for the humans and massive amounts of grass for the livestock.

👉 See also: Most Beautiful Buildings in the World: What Most People Get Wrong

When they hit the Great Salt Lake Desert, the salt crust broke under the weight of the wagons. The oxen, crazed with thirst, bolted into the desert and disappeared. When you lose your "engine"—the oxen—your "vehicle" is just a wooden box full of useless heirlooms. James Reed, one of the leaders, ended up caching most of his goods in the sand.

Archaeologists are still finding bits of these camps. They find buttons, broken glass, and charred bone. These tiny coordinates on a map represent the moment a family gave up on their past life to try and save their future one.

How to Explore the Route Today

If you want to trace this yourself, start at the Nevada-California border and follow Interstate 80. The highway roughly parallels the original route, but the interstate engineers had dynamite and heavy machinery. The emigrants had shovels and gravity.

- Stop at the Emigrant Trail Museum. They have the best physical donner party trail map reconstructions available.

- Hike the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT) section near the pass. You can look down onto the lake and see exactly why the granite cliffs were an impassable wall in 1846.

- Check out the "Roller Pass." This wasn't the exact Donner route, but nearby. It shows how emigrants used chains and windlasses to pull wagons up 45-degree inclines. It’s insane. You wouldn't want to walk it, let alone pull a 2,000-pound wagon up it.

The tragedy wasn't inevitable. That’s the hardest part to swallow when you look at the map. If they had stayed on the main trail, if they had left a week earlier, if they hadn't trusted Lansford Hastings—they would have been just another successful group of settlers.

Actionable Steps for History Enthusiasts

- Download the "Donner Party" Layer on Google Earth. Several historical societies have created KMZ files that overlay the 1846 coordinates onto modern 3D terrain. It’s the best way to see the elevation changes they faced.

- Visit in Late October. To get a feel for the "closing window," visit the pass right when the first dusting of snow hits. The drop in temperature is a visceral reminder of how fast the trap snapped shut.

- Read "Ordeal by Hunger" by George R. Stewart. While written decades ago, his topographical descriptions are still some of the best for matching the narrative to the actual dirt and rock.

- Support the Truckee-Donner Historical Society. They maintain the local archives and help preserve the sites that aren't inside the official state park boundaries.

Mapping the Donner Party isn't about morbid curiosity. It’s about understanding human error and the unforgiving nature of the American West. The map shows us that the line between a new life and a tragic end is often just a few miles of granite and a few days of bad timing.