Look at a globe. Your eyes probably drift toward that massive green ribbon slicing through the beige expanse of the Sahara. That is the Nile. Most people think they know where it is, but honestly, if you were trying to find the nile on a map with actual precision, you’d realize it’s a bit of a geographical mess. It isn’t just one river. It’s a massive, sprawling system that fights against the very desert it creates.

The Nile is long. Really long. Most geographers, including those at National Geographic, peg it at about 4,130 miles. But here is the thing: there is a constant, almost petty argument in the scientific community about whether the Nile or the Amazon is truly the longest. Recent satellite imagery suggests the Amazon might actually have a secret tail that makes it longer, but for most of us, the Nile remains the undisputed king of African geography.

When you trace the nile on a map, you aren't just looking at water. You’re looking at the lifeblood of eleven different countries. Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kenya, Ethiopia, Eritrea, South Sudan, Republic of the Sudan, and Egypt all have a stake in this water. It’s a political powder keg.

The Great Source Mystery

Where does it start? That's the question that drove Victorian explorers like Richard Burton and John Hanning Speke absolutely mad. If you pull up the nile on a map today, you'll see it begins in two main branches: the White Nile and the Blue Nile.

The White Nile is the steady one. It starts way down in the Great Lakes region of Africa. Most people point to Lake Victoria as the source, but if you want to be a technical nerd about it, the "true" source is likely the Kagera River in Burundi or Rwanda. It flows north through treacherous swamps called the Sudd. The Sudd is a nightmare for navigation. It's a massive wetland in South Sudan where the river basically turns into a giant, shifting maze of papyrus and hippos. You can’t even really see a clear "river" there on most satellite views; it just looks like a flooded green sponge.

💡 You might also like: Getting the Best Grand Central Station NYC Pictures Without the Tourist Traps

Then you have the Blue Nile. This is where the muscle comes from. It starts in Lake Tana in the Ethiopian Highlands. While the White Nile is longer, the Blue Nile provides about 80% of the water and silt that actually reaches Egypt. When the summer rains hit Ethiopia, the Blue Nile turns into a raging torrent. It’s the reason ancient Egypt had its famous "inundation" or flooding seasons.

The Khartoum Handshake

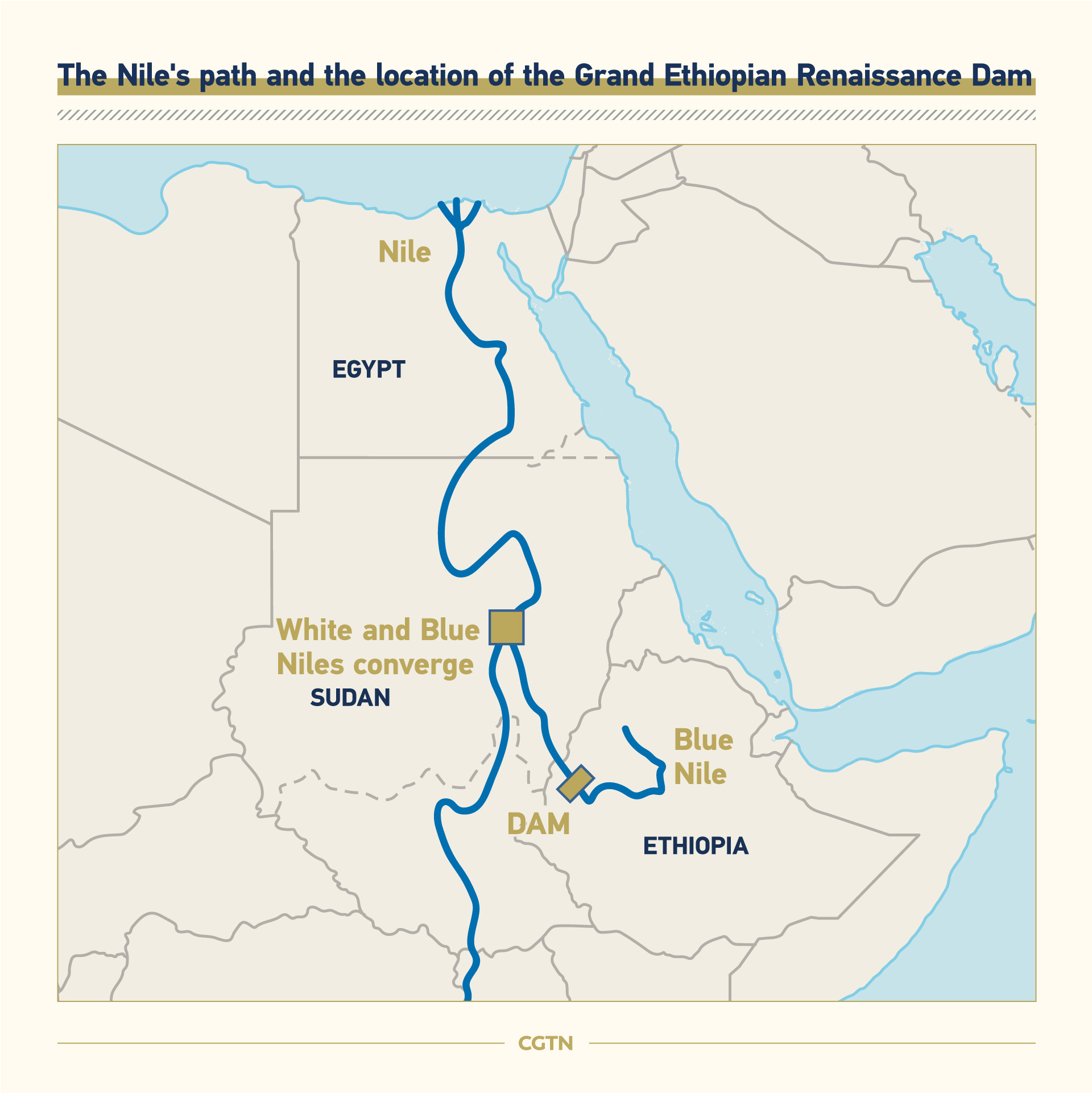

In the city of Khartoum, Sudan, these two giants finally meet. This is the "Confluence." On a high-resolution map, it’s actually pretty cool to see. You can literally see the darker, silt-heavy water of the Blue Nile mixing with the clearer, lighter water of the White Nile. From this point on, the river is just known as the Nile.

It still has one more major guest to welcome: the Atbara River. After the Atbara joins north of Khartoum, the Nile doesn't receive another single drop of perennial water from a tributary for the rest of its journey to the Mediterranean. It just braves the desert alone for 1,500 miles. Think about that. The sun is beating down, the sand is thirsty, and the river just keeps pushing through some of the hottest places on Earth without any help. It’s a miracle of physics.

Why the Nile on a Map Looks Different Today

If you looked at a map of the Nile from 1950 and compared it to one from 2026, you would notice a massive difference in Southern Egypt. That difference is Lake Nasser.

The Aswan High Dam changed everything. Before the dam, the Nile was wild. It flooded every year, bringing fertile black soil to the banks. Now, the flow is controlled. Lake Nasser is one of the largest man-made lakes in the world, and it’s so big you can see it easily from space. It provides electricity and water security, but it also trapped all that beautiful silt. Now, Egyptian farmers have to use chemical fertilizers because the "natural" map of the river has been fundamentally altered by human engineering.

There is also the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). This is a huge deal. Ethiopia built this massive dam on the Blue Nile, and it has caused years of diplomatic tension with Egypt. Egypt is terrified that if Ethiopia holds back too much water, the nile on a map will start to look like a withered thread by the time it reaches Cairo. It’s a reminder that geography isn't just about rocks and water; it's about survival and power.

Navigating the Delta

As the river nears the Mediterranean, it gets tired. It slows down and spreads out into the Nile Delta. This is the classic "triangle" shape you see in every geography textbook. The Greeks called it a "Delta" because it looked like their letter $\Delta$.

The Delta starts just north of Cairo. The river splits into two main distributaries: the Rosetta branch to the west and the Damietta branch to the east. This area is incredibly green, packed with farms and millions of people. But it's also sinking. Between rising sea levels and the lack of new silt from the upstream dams, the Delta is actually eroding. In our lifetime, the shape of the nile on a map at the coast is going to change as the Mediterranean creeps further inland.

How to Actually Read the Nile

If you're looking at a physical map, don't just look for the blue line. Look for the "Green Belt." In Egypt, the habitable land is basically only a few miles wide on either side of the river. Beyond that? Nothing. Just void.

- The Cataracts: These are shallow stretches where the water gets rocky and choppy. There are six major cataracts between Aswan and Khartoum. They historically acted as natural barriers, making it hard for ancient armies to sail south.

- The Qena Bend: Look for the spot in Egypt where the river takes a sharp turn toward the Red Sea and then hooks back. That’s the Qena Bend. It’s one of the most distinctive features of the river’s path.

- The Sudd: As mentioned, this is the swampy mess in South Sudan. It’s so flat that the river loses half its water to evaporation here before it even gets to the desert.

Honestly, the Nile is a bit of a freak of nature. Most rivers flow toward the equator or follow the tilt of the land toward the nearest ocean. The Nile flows south to north, crossing multiple climate zones. It starts in a tropical rainforest and ends in a Mediterranean climate, passing through a scorching desert in between.

Practical Steps for Map Enthusiasts and Travelers

If you are trying to study the Nile or plan a trip, don't just rely on Google Maps. It’s great, sure, but it doesn't give you the scale of the elevation changes.

- Use Topographic Layers: Look at the Ethiopian Highlands. You'll see why the Blue Nile is so powerful—it’s dropping from an elevation of over 6,000 feet. The gravity alone is doing most of the work.

- Check Seasonal Satellite Imagery: If you look at the Sudd or the Delta in August versus January, the color of the map actually changes. The "green" expands and contracts based on the rains in the south.

- Investigate the "Lost" Branches: Ancient maps of the Nile show more branches in the Delta that have since dried up or been filled in. If you're a history buff, finding the "Pelusiac" or "Canopic" branches on historical overlays is a rabbit hole you'll never come out of.

- Monitor the GERD Reservoir: Use tools like Sentinel-2 imagery to see how the water levels in Ethiopia are changing. It gives you a real-time look at how human intervention is reshaping the African continent.

The Nile isn't a static line on a piece of paper. It’s a living, breathing, and currently shrinking entity. Whether you’re looking at it for a school project or just because you’re bored and like looking at the world, remember that every bend in that river has a thousand years of history behind it. The nile on a map is just the beginning of the story. You have to look at the silt, the dams, and the swamps to really see it.

To get the most out of your geographical research, start by comparing the White and Blue Nile junctions on a satellite view versus a political map. You will see how city borders are literally carved by the water's edge. This helps in understanding why urban planning in North Africa is so uniquely linear compared to the sprawling cities of Europe or America.