Records matter. Names matter. When you start digging into the vietnam prisoners of war list, you realize pretty quickly that it’s not just a dry document or a spreadsheet tucked away in a government basement. It’s a messy, emotional, and frankly exhausting piece of history that still isn't fully "closed" for a lot of families. Honestly, if you’re looking for a single, definitive list that everyone agrees on, you’re going to be disappointed because the data changes depending on who you ask and how they define a "prisoner."

History is loud.

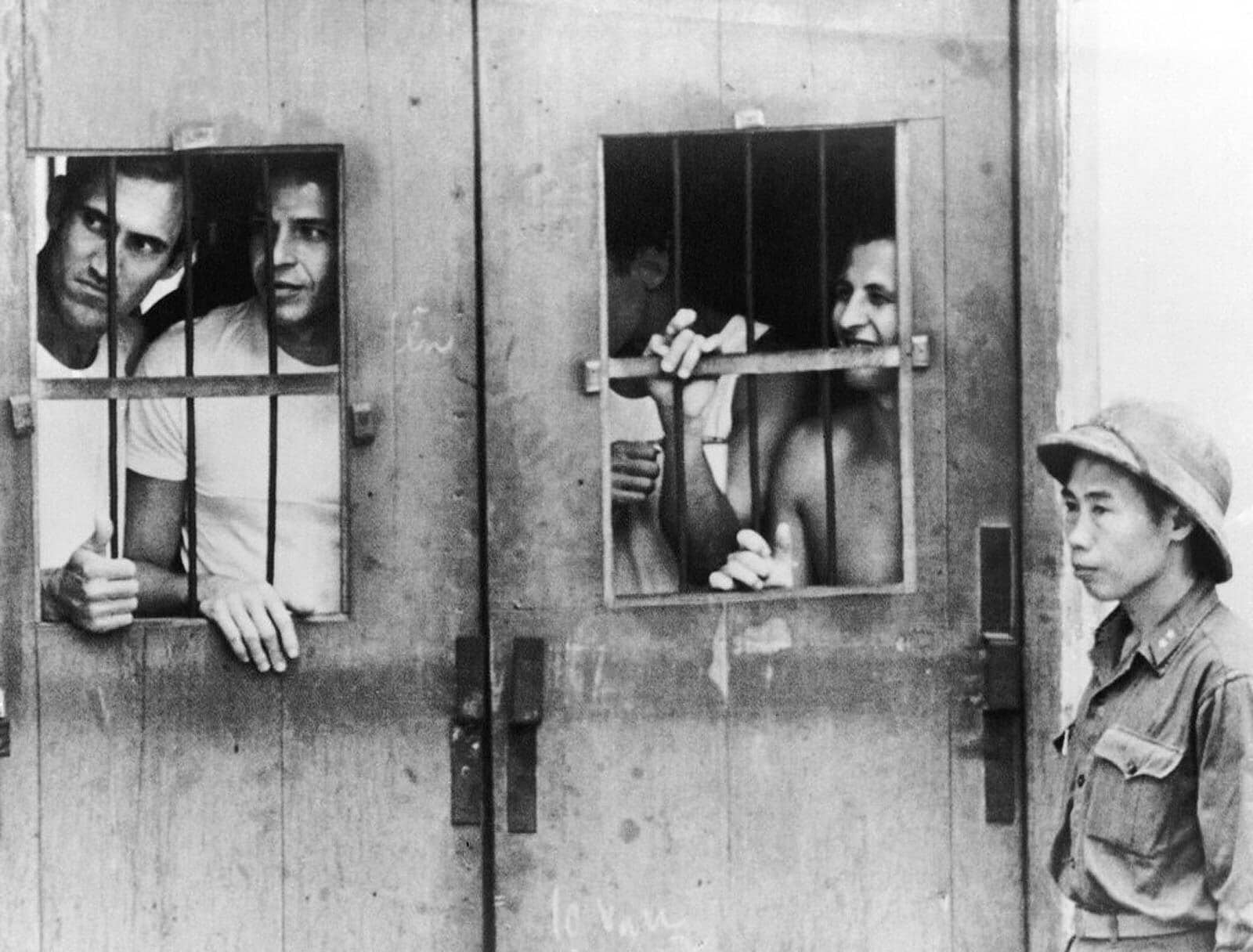

During the conflict, specifically between 1964 and 1973, hundreds of Americans were held in North Vietnam, South Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, and even China. Most people think of the "Hanoi Hilton"—Hỏa Lò Prison—but the reality was a network of camps, some just bamboo cages in the jungle. When Operation Homecoming happened in 1973, 591 POWs came home. That number is the bedrock of the official vietnam prisoners of war list, but it doesn’t tell the whole story of those who died in captivity or those who were never accounted for.

🔗 Read more: Peace Process Israel Palestine: Why the New 2026 Reality Is So Messy

The Official Record vs. The Reality of the "Missing"

The primary source for any legitimate vietnam prisoners of war list is the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA). They are the ones doing the heavy lifting, digging up crash sites in the jungles of Southeast Asia to this day. But here’s the kicker: the list isn't just about the guys who sat in a cell. It’s intertwined with the MIA (Missing in Action) records.

When the war ended, there were roughly 2,646 Americans unaccounted for. As of early 2026, that number has dropped to about 1,574. That’s still over 1,500 families waiting for a name to move from one list to another. It’s heartbreaking.

You have to understand the categories.

The Department of Defense breaks it down into "Returned alive," "Died in captivity (remains recovered)," and "Died in captivity (remains not recovered)." If you see a list online that just dumps names into one bucket, it's probably wrong. For instance, Navy Captain Jeremiah Denton—who famously blinked "T-O-R-T-U-R-E" in Morse code during a televised propaganda interview—is a cornerstone of the "Returned" list. Then you have guys like Air Force Colonel Peter Flynn, who spent years in the camps. Their stories are documented, verified, and etched into the public record.

But what about the "last known alive" cases? This is where the vietnam prisoners of war list gets controversial. Throughout the 80s and 90s, there was this massive cultural movement—think Rambo or Missing in Action—based on the idea that Americans were still being held in secret jungle camps. While the Senate Select Committee on POW/MIA Affairs, led by John Kerry and John McCain (both Vietnam vets, McCain himself a famous POW), concluded in 1993 that there was "no compelling evidence" of living survivors, many activists still dispute this. They point to satellite photos of "pilot distress signals" carved into the ground. It’s a rabbit hole.

Why the Data is So Fragmented

If you want to find a specific person, you can't just Google a single PDF. You've got to cross-reference.

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund (the folks behind The Wall in D.C.) maintains a database. The National Archives has the "Records of Military Personnel Who Were Prisoners of War during the Vietnam War." It's a lot of clicking.

One major issue is the "service-connected" versus "hostile" distinction. Not everyone who was captured was a pilot shot down over Hanoi. Some were civilians. Some were captured during the Tet Offensive in cities like Huế. Bobby Muller, a prominent veteran advocate, has often spoken about the chaos of the front lines—how hard it was to even know who was captured versus who was vaporized in an explosion.

- The Navy/Air Force Bias: Most of the well-known names on the vietnam prisoners of war list are officers. Pilots. This is because North Vietnam saw them as high-value bargaining chips.

- The Grunts: Army and Marine personnel captured in the South often faced much more brutal, transient conditions. Their survival rates were lower, and their record-keeping was spottier because they were often held by the Viet Cong in moving camps rather than the NVA in established prisons.

- The "Stay-Behinds": There are a handful of documented cases of defectors—Robert Garwood being the most famous—who were technically prisoners but whose status on "the list" is a subject of intense, often angry debate among veterans.

How to Verify a Name Today

Maybe you found a POW/MIA bracelet in a thrift store. Or maybe a family legend says Great Uncle Jim was in a camp. How do you actually check the vietnam prisoners of war list without getting scammed by those "people search" sites?

First, go to the DPAA website. They have a searchable database by name, service branch, and "Home of Record." It is the only "gold standard" for factual accuracy.

💡 You might also like: Rage Against No Shelter: Why the Global Housing Crisis is Boiling Over

Second, check the Library of Congress. They have a specific Vietnam Era POW/MIA Database that includes declassified intelligence reports. Sometimes you’ll find "sightings" of a soldier that were reported by villagers but never confirmed. It’s eerie to read.

Third, look at the NAM-POW organization records. This is a group of the actual returnees. They keep their own history, and it's incredibly detailed. They know who was in the cell next to them. They know who didn't make it out of the "Zoo" or "Dirty Bird" camps.

The Psychological Toll of the List

We can't talk about these names without talking about the "Homecoming" syndrome. For the 591 who returned in 1973, being on the "alive" list was just the start of a new battle. They came home to a country that was divided, to put it mildly.

They were used as political props by the Nixon administration and then, in many ways, forgotten until the 1980s when the POW/MIA flag (that black and white one you see at post offices) became a permanent fixture of American life. That flag is actually the only flag other than the Stars and Stripes to fly over the White House and be displayed in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda. That tells you everything about the weight of the vietnam prisoners of war list.

📖 Related: Finding Cox Funeral Home Walnut Ridge Obituaries: A Local Guide to Keeping Up

The Search Continues in 2026

You might think this is all settled history. It isn't.

Even now, teams of archaeologists and military specialists are in Southeast Asia. They are looking for teeth, bone fragments, and zippers. Every time they find a match, a name is moved on the vietnam prisoners of war list. The status changes from "Unaccounted For" to "Accounted For."

It’s expensive work. It’s slow. But for the families of the 1,574 still missing, that list is the most important document in the world.

If you are researching this, be careful with "memoir" sites. Stick to the National Archives (RG 330) or the DPAA. There are a lot of "stolen valor" stories out there where people claim to have been POWs when they were actually stationed in Guam. The real list is a sacred thing to those who were actually there.

Actionable Steps for Researchers

If you are looking for a specific individual on the vietnam prisoners of war list, follow this sequence to get the most accurate result:

- Start with the DPAA "Our Missing" tool. Filter specifically by the Vietnam War. This gives you the current status of remains recovery.

- Consult the National Archives (AAD). Use the "Records of World War II Prisoners of War" and "Prisoners of War of the Vietnam Era" databases. You'll need a last name and preferably a service number.

- Cross-reference with The Wall of Faces. This tool, managed by the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, allows you to see photos and leave comments. Often, fellow platoon members will post details about a capture that aren't in the official military brief.

- Check the "Last Known Alive" (LKA) lists. If the name is part of the 196 specific cases identified by the 1992 Senate Committee, the documentation will be much more extensive and likely involve declassified CIA "bright light" rescue mission reports.

Don't rely on Wikipedia for this. The nuances of "Discrepancy Cases"—where the US thinks the Vietnamese government has more info than they're letting on—are too complex for a crowd-sourced encyclopedia. Stick to the primary source documents from the Task Force Russia or the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command (JPAC) archives.

The list is more than names. It is a record of what happens when a country goes to war and the long, painful process of trying to bring everyone home, even if it’s decades late.