Yellowstone is huge. I mean, it's genuinely massive—larger than Rhode Island and Delaware combined. When you first look for yellowstone on a map, you see this neat, tidy rectangle sitting in the top-left corner of Wyoming. But that little box is a bit of a geographical lie. It’s actually a sprawling 2.2-million-acre wilderness that spills over into Montana and Idaho, and honestly, if you don't understand the layout before you shift into drive, you’re going to spend your entire vacation staring at the bumper of a rental SUV.

People think they can "do" Yellowstone in a day. You can't. Not unless you enjoy eight hours of white-knuckle driving and zero hiking.

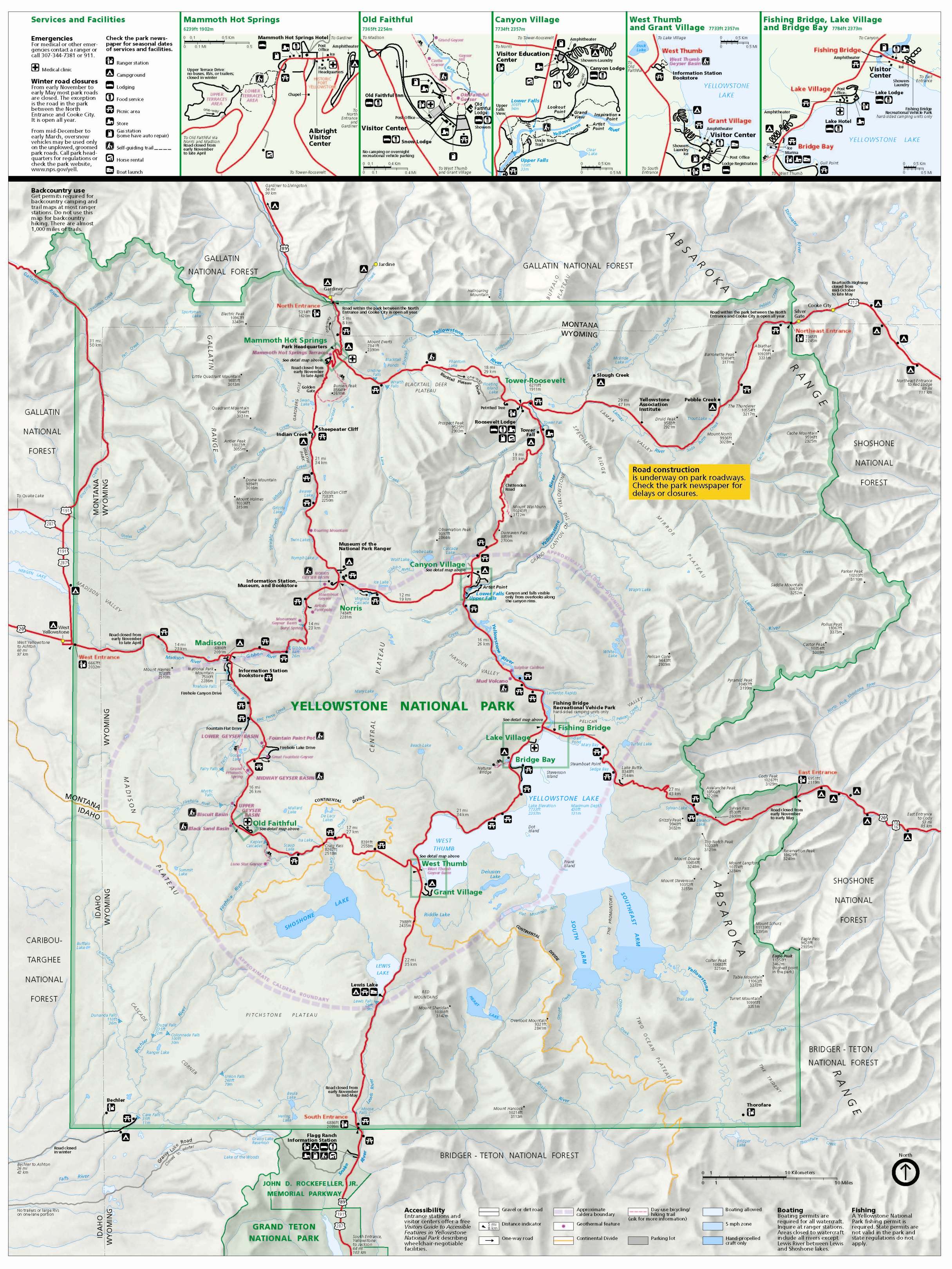

The park is essentially a high-altitude plateau, rimmed by mountain ranges. Most of the "action"—the geysers, the mud pots, the canyon—is centered around a road system called the Grand Loop. Think of it like a giant, wobbly figure-eight. If you look at the park's topography, you'll see it’s basically sitting on top of a giant lid. That lid is the Yellowstone Caldera, a "supervolcano" that last blew its top about 640,000 years ago. When you're standing in the middle of the park, you’re literally standing inside the crater.

The Five Entrances (and Why One is Probably Wrong for You)

If you're looking at yellowstone on a map for the first time, your eyes probably gravitate toward the West Entrance. It's the most popular. West Yellowstone, Montana, is a classic gateway town with plenty of motels and overpriced t-shirts. It drops you right near the Madison River and gives you the quickest shot to the geyser basins. But here’s the thing: it’s a bottleneck. During July, the line to get through the gate can be an hour long.

The North Entrance at Gardiner is the only one open year-round. It’s home to the iconic Roosevelt Arch. If you’re coming from Bozeman, this is your spot. You get immediate access to Mammoth Hot Springs, which looks like a melting wax museum made of travertine.

Then there’s the Northeast Entrance near Silver Gate and Cooke City. This is the "back door." It’s rugged. It’s isolated. It takes you through the Lamar Valley. Scientists and hardcore wildlife photographers call this the "Serengeti of North America." If you want to see wolves or grizzlies at dawn, you need to be on this specific section of the map.

The East Entrance (from Cody) and the South Entrance (from Grand Teton) offer totally different vibes. The East Entrance climbs over Sylvan Pass, which is beautiful but can be terrifying if you hate heights. The South Entrance is basically a two-for-one deal since you drive through Grand Teton National Park to get there. It’s the most scenic route, hands down.

Mapping the "Figure Eight" Logistics

The Grand Loop Road is the spine of the park. It’s 142 miles of asphalt that connects all the major sights. On a map, it looks simple. In reality, it’s a lesson in patience. The speed limit is 45 mph, but you’ll rarely hit that. Why? Bison.

Bison don't care about your dinner reservations.

A "bison jam" is a real geographical phenomenon where one 2,000-pound animal decides to take a nap in the middle of the road. On a map, the distance between Old Faithful and Canyon Village looks short. In reality, that drive can take two hours if a herd is on the move.

💡 You might also like: Mt Hutt Live Cam: Why It Is The Only Tool You Need To See Before Driving Up

The Upper Loop contains Mammoth Hot Springs, the Tower-Roosevelt area, and the Lamar Valley. This is where the geology gets older and the mountains get sharper. The Lower Loop is the geothermal powerhouse. This is where you find the Grand Prismatic Spring—that giant rainbow-colored eye that everyone sees on Instagram—and, of course, Old Faithful.

Why Elevations Matter More Than Miles

When you study yellowstone on a map, pay attention to the contour lines. The park’s average elevation is about 8,000 feet. That matters for two reasons: your lungs and your radiator.

- Dunraven Pass: This is the highest point on the Grand Loop at 8,859 feet. Even in June, it might be snowing here.

- The Continental Divide: The map shows this line zig-zagging through the park. In some spots, you’ll cross it three times in ten miles.

- Yellowstone Lake: It’s the largest high-elevation lake in North America. It’s so big it has its own weather patterns. It sits at 7,733 feet and stays freezing cold all year.

Misconceptions About the Geyser Basins

Everyone zooms in on Old Faithful when looking at the map. It’s the celebrity. But the Upper Geyser Basin (where Old Faithful lives) is actually packed with dozens of other features. Most people walk the boardwalk, see the big eruption, and leave. That’s a mistake.

If you hike just a mile or two past the visitor center, you’ll find Morning Glory Pool. It’s deep, brilliantly blue, and much quieter.

West Thumb Geyser Basin is another weird one. On the map, it looks like a tiny thumb sticking out of Yellowstone Lake. It’s unique because some of the geysers are actually underwater or right on the shoreline. You can see boiling water bubbling up through the freezing lake water. It’s a bizarre contrast that highlights how thin the Earth’s crust is right here.

The Lamar vs. Hayden Debate

If you want to see animals, you have to choose your valley.

Hayden Valley is centrally located on the map, between Canyon and Yellowstone Lake. It’s prime grizzly territory. Because it's an old lakebed, it's lush and open. You’ll see thousands of bison here.

Lamar Valley, in the northeast, is further away. It’s a long drive. But because it’s more remote, the wolf packs are more active. If you’re a "birder" or a serious tracker, the Lamar is your holy grail.

Connectivity and the "No Service" Reality

Here is the most important thing about yellowstone on a map: don't rely on the one on your phone.

Cell service is nonexistent in about 90% of the park. Your Google Maps or Apple Maps will likely freeze, or worse, try to send you down an old fire road that hasn't been used since 1974.

You need a physical map. A real, paper one.

The National Park Service hands out a free map at the entrance gates. It’s surprisingly good. It marks every picnic area, every restroom, and every gas station. Keep it. Use it. Also, download offline maps before you leave your hotel in West Yellowstone or Cody.

Actionable Steps for Navigating Yellowstone

Mapping out a trip here requires more than just picking a spot and hitting "Go." You have to think like a ranger.

1. Pick your "Anchor" Entrance

Base your lodging on what you want to see most. If you want geysers, stay in West Yellowstone or Old Faithful Inn. If you want wildlife, stay in Gardiner or Silver Gate. Switching between these can take 3-4 hours of driving, so don't try to move bases every night.

2. Follow the "Early or Late" Rule

The Grand Loop turns into a parking lot between 10:00 AM and 4:00 PM. If you want to see Grand Prismatic without 5,000 other people, be at the trailhead by 7:00 AM. Or, wait until 6:00 PM when the tour buses have cleared out. The lighting is better for photos then anyway.

3. Respect the Distances

Treat the park like two separate trips. Spend two days on the Upper Loop and two days on the Lower Loop. Trying to see the whole "figure eight" in one day is a recipe for burnout and a very cranky family.

4. Check Road Status Constantly

Yellowstone’s roads are under perpetual repair. The "map" changes because sections close for construction or snow. Check the NPS Yellowstone Road Page every single morning before you head out. A closed road between Canyon and Tower can add three hours to your detour.

5. Mark Your Gas Stations

There are only a handful of places to get fuel: Mammoth, Tower Junction, Canyon, Fishing Bridge, Grant Village, and Old Faithful. If your tank hits half, and you see a station on the map, stop. You do not want to be stranded in a place where the local residents are bears.