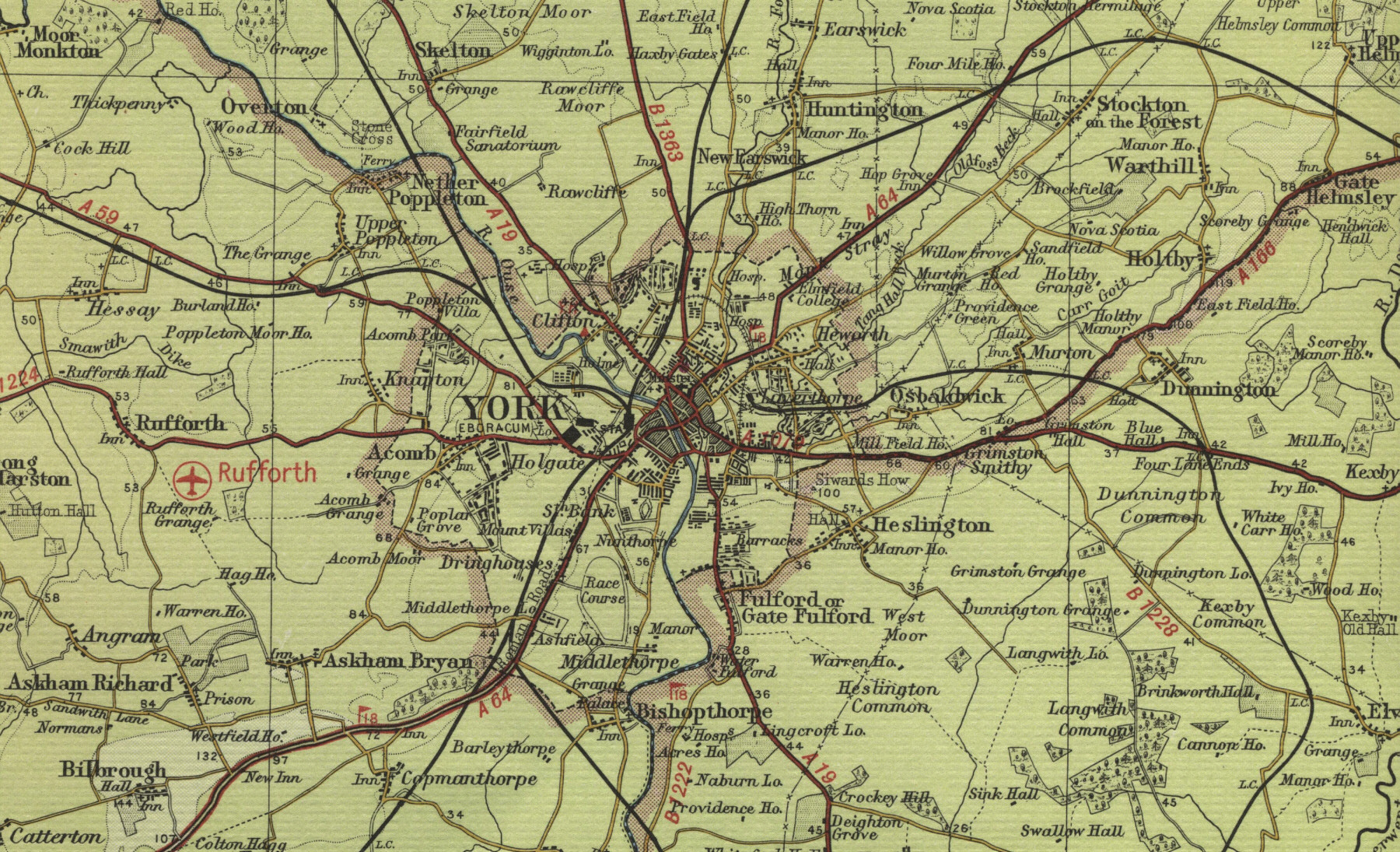

Look at a map of England. Right in the middle—well, slightly to the east of the spine of the Pennines—you’ll spot York. It’s that tangled knot of medieval streets sitting exactly where the River Ouse meets the River Foss. People often assume it's just another northern city, but York on a map acts as a historical compass for the entire United Kingdom. If you zoom out, you see it’s roughly halfway between London and Edinburgh. That’s not an accident. The Romans, who weren't exactly known for picking bad real estate, saw this specific geography in 71 AD and decided it was the perfect spot to build Eboracum.

They were right.

Honestly, finding York on a map is easy; understanding why it's there is the tricky part. The city sits in the Vale of York, a flat expanse of fertile land sandwiched between the North York Moors to the northeast and the Yorkshire Dales to the west. This positioning made it a natural fortress. You had high ground on both sides and a swampy, river-heavy basin in the middle that was surprisingly easy to defend if you knew where to place your walls.

The Geographic "Sweet Spot"

When you search for York on a map today, you’re looking at a transport hub, but back in the day, it was all about the water. The Ouse provided a direct line to the North Sea via the Humber Estuary. This meant Viking longships could sail right into the heart of the city. That's exactly what they did in 866. They didn't just raid it; they stayed. They called it Jorvik. If you look at the street names on a modern digital map—Stonegate, Micklegate, Coppergate—that "gate" suffix doesn't mean a literal door in a wall. It comes from the Old Norse gata, meaning street.

The geography shaped the linguistics.

It’s kinda wild how the physical constraints of the rivers still dictate how you move through the city. Even with GPS, people get turned around because the medieval layout ignores the logical grid systems found in places like Manchester or Leeds. The walls are the giveaway. If you see that irregular, stony ring on a satellite view, you're looking at one of the best-preserved medieval fortifications in Europe. It’s about 2 miles of walkable history that literally outlines the ancient city limits.

Why the Location Matters More Than You Think

Most people forget that York was basically the "Capital of the North" for centuries. During the Middle Ages, it was the second city of England. The map shows why: it controls the bottleneck of northern travel. If you wanted to go from the south of England to Scotland without climbing over mountains or drowning in a marsh, you had to pass through York.

This strategic importance is why York Minster is so massive. It’s not just a church; it’s a geographical statement of power. When you're looking at the city from an aerial perspective, the Minster is the undisputed North Star. Everything else radiates out from it.

Navigating the Modern Map

Let's get practical for a second. If you're planning a trip and trying to pin York on a map, don't just look for the city center. Look at the "A" roads that converge there like a spiderweb. The A64 is the big one, connecting it to Leeds and the coast. But the real secret to York’s modern geography is the railway.

👉 See also: Grandeur of the Seas Itinerary: What Most Cruisers Get Wrong About These Routes

York railway station was once the largest in the world. Even now, it’s a massive junction on the East Coast Main Line. You can get from London King’s Cross to York in about an hour and fifty minutes. That’s faster than some people’s daily commute within London. Because of this, the "map" of York has expanded. It's no longer just a museum city; it's a commuter hub for people who want to live in a place with 13th-century walls but work in a 21st-century tech office.

Misconceptions About the North

There is this weird idea that York is "near" everything in the North. It's not.

- Manchester? It's a solid hour and a half away.

- The coast? You're looking at an hour to get to Scarborough.

- The Dales? You'll be driving for at least 45 minutes before you see a limestone pavement.

York is its own island, geographically speaking. It sits in that flat "Vale" I mentioned earlier. This means that while the city itself is incredibly walkable, the surrounding landscape is surprisingly agricultural. If you're looking at a topographical map, you'll see a lot of green and a lot of very low numbers for elevation. This lack of hills is why everyone in York owns a bicycle. It’s basically the Amsterdam of England, minus the legal weed and with significantly more Vikings.

📖 Related: The Inn at Gig Harbor: What Most People Get Wrong About This PNW Landmark

The "Snickelways" and Hidden Cartography

You won't find the "Snickelways" on a standard Google Map. Not really. These are the tiny, narrow footpaths and alleys that cut through the city, often hidden behind unremarkable doors or between shops. Mark W. Jones coined the term in the 80s, combining the words "snicket," "ginnel," and "alleyway."

Mapping these is a nightmare for software. The GPS signal bounces off the overhanging timber-framed buildings of The Shambles, making your blue dot jump around like it's had too much espresso. To truly map York, you have to put the phone away and look at the floor. The paving stones often change when you cross from the old Roman boundaries into the medieval ones.

The Flooding Factor

If you look at York on a map during the winter, you need to check the blue lines. The Ouse is a moody river. Because the city sits at the bottom of a massive drainage basin for the Dales, all that rainwater eventually ends up in the middle of York. The Kings Arms pub near Ouse Bridge has a famous chart on the wall showing flood levels from years past. Some of them are well above head height.

Modern engineering, like the Foss Barrier, tries to keep the city dry, but the map is constantly being rewritten by the water. Areas like Clementhorpe or the paths along the New Walk are frequently underwater. It’s a reminder that even in 2026, the ancient geography of the river still calls the shots.

Real-World Action Steps for Your Next Search

If you are actually trying to use a map to explore York, stop looking at the "Top 10" pins. Everyone goes to the Minster. Everyone goes to the Shambles.

- Check the "Bars": On a York map, a "Bar" is a gatehouse. Bootham Bar, Monk Bar, Walmgate Bar, and Micklegate Bar. Use these as your cardinal points. If you know which Bar you’re near, you know exactly where you are in relation to the center.

- Look for the "Strays": These are massive areas of common land—like Knavesmire or Monk Stray—that have never been built on. They offer the best views of the skyline and are usually where the locals actually hang out.

- The Railway Museum Shortcut: Most maps tell you to walk around the long way. There’s a secret pedestrian tunnel near the station that saves you ten minutes.

- Elevation Matters: If you want the best "map view" without a drone, climb the steps to the top of Clifford’s Tower. You’ll see the entire layout of the Roman and Viking city sprawling beneath you.

York isn't just a coordinate. It's a layers-of-an-onion situation where every map you look at—be it Roman, Medieval, Victorian, or Digital—is stacked on top of the other. The streets don't make sense because they weren't designed for cars; they were designed for people carrying shields and, later, for people carrying wool.

When you look at York on a map, remember you aren't just looking at a location in North Yorkshire. You're looking at the reason England looks the way it does today. The city was the hinge that held the North and South together. It still is. Get a physical map, find the rivers, and follow the walls. That’s the only way to actually see it.