It is a speck. Honestly, if you look at a standard world map, South Georgia Island is barely a pixel of grit in the vast, churning blue of the Southern Ocean. Most people confuse it with the state of Georgia in the US or the country in the Caucasus. Big mistake. This place is a 100-mile long crescent of rock, ice, and screaming fur seals located about 800 miles southeast of the Falkland Islands. It’s remote. It’s rugged.

If you’re looking at a map South Georgia Island appears like a jagged tooth pulling away from the Antarctic Peninsula. But here’s the thing: it isn't actually part of Antarctica. It’s a British Overseas Territory. It sits just above the 60-degree South latitude line, which is the official "border" of the Antarctic Treaty. This distinction matters because the rules for visiting, the wildlife you’ll see, and even the weather are totally different from the icy continent to the south.

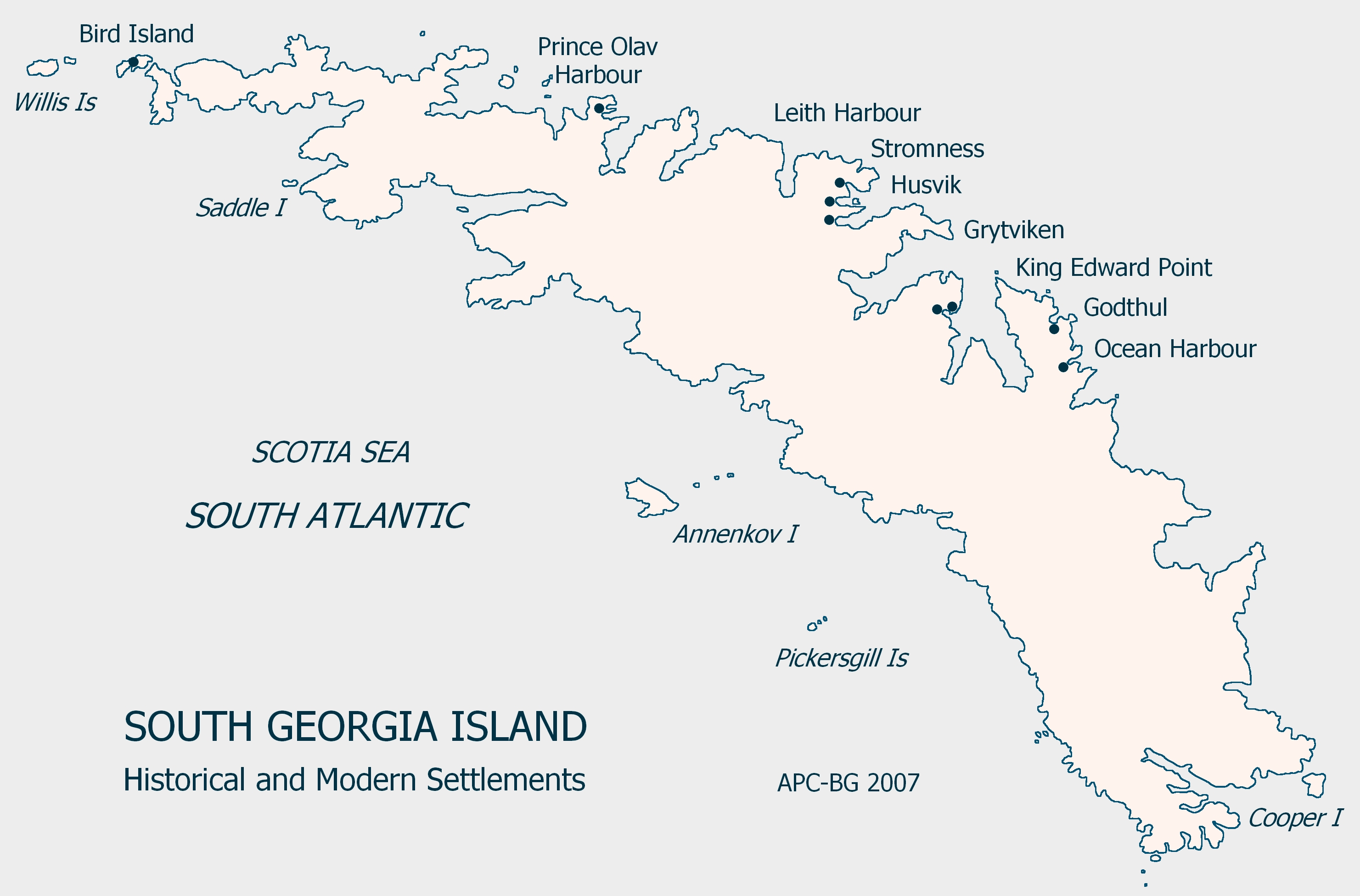

Navigating the Rugged Coastline

The first thing you notice when you pull up a detailed topographic map of the island is the north coast versus the south coast. They are worlds apart. The southwest coast is hammered. It takes the full brunt of the "Furious Fifties" winds. Huge swells from the Drake Passage smash into these cliffs constantly. Navigation here is a nightmare, and very few expedition ships even try to land on the southern side because the risk of being blown onto the rocks is just too high.

On the flip side, the northeast coast is where the magic happens. It’s the leeward side. You have these deep, finger-like fjords that provide at least a little bit of shelter from the relentless wind. This is where you find the legendary spots: Salisbury Plain, St. Andrews Bay, and Gold Harbour. When you look at the map South Georgia Island features on this side, you’ll see dozens of small coves. Each one is packed—and I mean absolutely carpeted—with King Penguins. We’re talking colonies of 200,000 birds. It’s loud. It’s smelly. It’s incredible.

The Stromness To Grytviken Track

You can't talk about mapping this place without mentioning Ernest Shackleton. In 1916, Shackleton and two others crossed the mountainous interior of the island to reach help after their ship, the Endurance, was crushed by ice. They didn't have a map. They had a rough idea and a lot of desperation.

Today, you can actually trace their path on a modern map. Most travelers try the "Shackleton Walk," which covers the final leg from Fortuna Bay to Stromness. It’s only about 3.5 miles, but the terrain is brutal. You’re dealing with scree slopes, boggy marshland, and the constant threat of a "katabatic" wind—those are gravity-driven winds that can scream down off a glacier at 80 miles per hour without warning.

- Start at Fortuna Bay: Watch out for the fur seals; they are aggressive and will bite.

- The Ascent: You climb up a steep ridge where the views of the Konig Glacier are just stupidly beautiful.

- The Waterfall: You descend past a waterfall where Shackleton had to use his last bit of rope.

- Stromness: You arrive at the rusted-out remains of the old whaling station. It’s eerie.

Why the Mountains Change Everything

The interior of South Georgia is basically the Alps dropped into the ocean. Mount Paget is the highest point, topping out at over 9,600 feet. That’s huge for such a narrow island. Because these mountains are so high and so steep, they create their own microclimates. You might have sunshine in one bay and a total whiteout blizzard in the next fjord over.

Glaciers are everywhere. Or, they used to be. If you compare a map South Georgia Island used 30 years ago to one from 2026, the difference is heartbreaking. The Neumayer Glacier has retreated miles back into the mountains. Where there used to be ice, there is now open water or raw, grey moraine. Scientists like those from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) use satellite mapping to track this. It’s changing the way ships navigate. Some bays that were blocked by ice a decade ago are now accessible, while others have become dangerous due to increased iceberg "calving."

Grytviken: The "Capital" That Isn't

Look at the middle of the island on the map. You’ll see a spot called Grytviken. It’s not a town in the way you’re thinking. Nobody lives there permanently. It’s an old whaling station turned museum. It’s also where Shackleton is buried.

The graveyard at Grytviken is a somber place. You see his headstone, but you also see the graves of young whalers who died in the early 1900s. It’s a reminder that this island was once an industrial hub for the oil industry—whale oil, that is. Today, the map reflects a different reality: a massive Marine Protected Area (MPA). The South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands MPA covers over a million square kilometers. It’s one of the largest in the world.

Practical Logistics: Getting There

You don’t just fly to South Georgia. There is no airstrip. No hotels. No Starbucks. Basically, if you want to see this place with your own eyes, you have to earn it.

📖 Related: Why 177a Bleecker Street NYC is the Weirdest Address in Greenwich Village

- Departure Points: Usually Ushuaia, Argentina or Stanley in the Falkland Islands.

- The Sea Crossing: It takes about two to three days of sailing across some of the roughest water on Earth. It’s called the "Drake Shake" for a reason.

- Permits: You can’t just show up. Every visitor has to be part of an organized expedition or have a permit from the Government of South Georgia & the South Sandwich Islands (GSGSSI).

- Biosecurity: This is huge. Before you step off the boat, you have to vacuum your pockets and scrub your boots. They are hyper-vigilant about preventing invasive species from reaching the island after a massive, multi-million dollar project successfully eradicated rats and mice a few years back.

The Best Time to Visit

Timing is everything. If you go in November, you see the elephant seal bulls fighting. These things weigh four tons and they are bloody and violent. It’s like watching a kaiju movie in real life. If you go in January, the King Penguin chicks are molting, looking like brown "oakum boys" in fluffy coats. By March, the fur seal pups are everywhere and they are incredibly curious—and slightly nippy.

The light in the Southern Ocean is weirdly crisp. Because there’s no pollution, the colors on the map—the greens of the Tussac grass, the deep blues of the glaciers, the grey of the scree—pop with an intensity that photos usually fail to capture.

What Most People Miss

When looking at a map South Georgia Island can seem one-dimensional. But the ocean floor around it is just as complex. The island sits on the Scotia Arc, a submarine mountain range that connects the Andes to the Antarctic Peninsula. This underwater topography forces nutrient-rich deep water to the surface.

This "upwelling" is why there is so much life. It creates a massive bloom of krill. Everything else—the whales, the seals, the millions of birds—is there because of the krill. If the ocean currents change, the whole ecosystem on the map shifts. We’re already seeing Albatross populations thinning out because they have to fly further and further to find food for their chicks. It’s a delicate balance.

Actionable Insights for Your Journey

If you’re serious about exploring this region, don't just rely on a digital map. Get a physical chart. There’s something about holding a paper map of the Southern Ocean that makes the scale sink in.

- Invest in high-end optics: You need 8x42 or 10x42 binoculars. You’ll be spotting Wandering Albatrosses with 11-foot wingspans. You don’t want to squint.

- Download offline maps: There is zero cell service. If you’re using a GPS or an iPad for navigation, make sure your maps are cached locally.

- Study the history: Read Endurance by Alfred Lansing before you look at the map. It turns the geography from lines on a page into a living, breathing story of survival.

- Check the BAS website: The British Antarctic Survey provides updated weather and ice data. It’s the gold standard for anyone heading south of the convergence.

The reality of South Georgia is that it is a place of extremes. It’s beautiful but indifferent to your presence. Whether you’re a birder, a history buff, or just someone who wants to see the end of the world, the map is only the beginning. The actual experience of standing on a beach with 100,000 penguins while a glacier groans in the background? That’s something no piece of paper can ever fully explain.

To get the most out of your research, look for high-resolution satellite imagery from the European Space Agency’s Sentinel satellites. They offer a "live" look at ice coverage that traditional maps just can't beat. Study the contours of Drygalski Fjord on the southern tip; it’s one of the most dramatic geological features on the planet, with rock walls that rise straight out of the water. Planning your route around these geological highlights ensures you see the island’s most raw, unedited landscapes.