Maps are weirdly addictive. You start looking for a specific city and suddenly you’re tracing the jagged edge of the Maine coastline or wondering why the border between Colorado and Wyoming looks like a perfect ruler stroke. But if you’ve ever looked at a latitude longitude US map and felt like you were staring at a high school geometry final, you aren't alone. Most people see those crisscrossing lines and think they’re just decorative. They aren't. They are the literal "address" of every square inch of dirt from the Florida Keys to the Olympic Peninsula.

Coordinates matter.

If you’re a hiker, a pilot, or just someone who gets geeky about geography, understanding these invisible lines changes how you see the country. It’s not just about "up" and "down." It’s about how we’ve chopped up the planet into a grid so precise that a search-and-rescue team can find a specific tent in the middle of the Alaskan wilderness. Honestly, it’s kinda wild that we can do that with just two sets of numbers.

Why the Latitude Longitude US Map is the Secret Language of Navigation

We live in a GPS-saturated world. You pull out your phone, tap an icon, and a blue dot tells you exactly where you are. But that blue dot is just a user-friendly skin over a massive amounts of data—specifically, the geographic coordinate system.

Latitude lines—the parallels—run east-west. Think of them like rungs on a ladder. They tell you how far north or south of the Equator you’ve wandered. For the United States, we’re strictly in the Northern Hemisphere. This means every latitude coordinate for a US map is going to be a "North" value. If you see a "South" value, you’ve somehow ended up in South America or the middle of the ocean, and you’ve got bigger problems than reading a map.

Then you have longitude. These are the meridians. They run north-south, connecting the poles, but they measure how far east or west you are from the Prime Meridian in Greenwich, England. Since the US is entirely in the Western Hemisphere, all our longitude numbers are "West."

The "Negative" Number Confusion

Here is something that trips people up constantly. In digital mapping software like Google Maps or Leaflet, you won’t always see "N" or "W." Instead, you’ll see positive and negative numbers. Since the US is North of the equator (positive) but West of the Prime Meridian (negative), a point in Kansas might look like 39.50, -98.35. That minus sign is just shorthand for "West." If you forget that little dash, you’ll find yourself looking at coordinates in China.

It’s a common mistake. I’ve seen data scientists mess that up in spreadsheets more times than I can count.

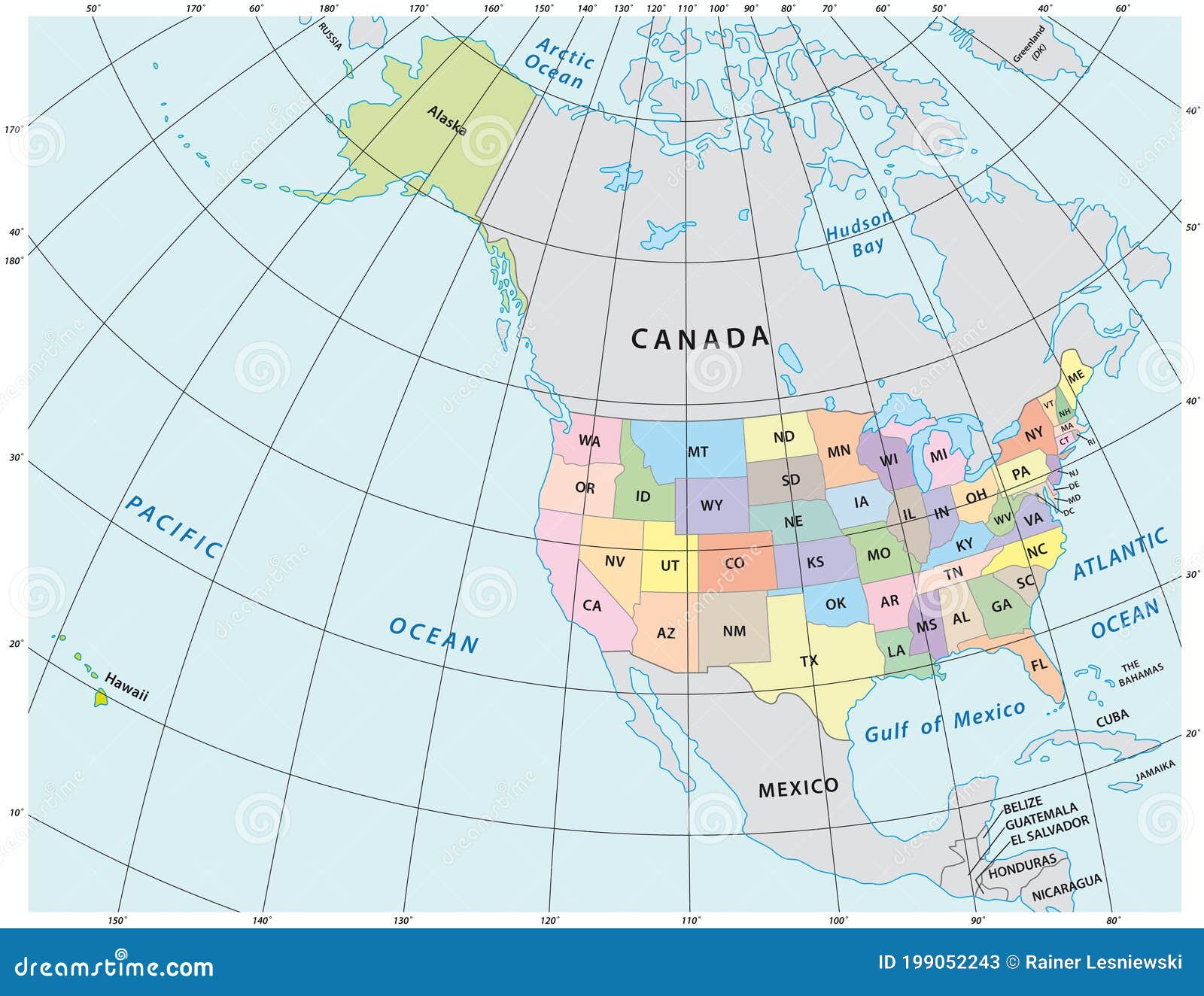

The Grid: Breaking Down the Lower 48

When you look at a latitude longitude US map, you’ll notice the numbers follow a very specific range. The "Lower 48" states—the contiguous US—basically live between the 24th and 49th parallels of latitude.

Florida’s southern tip is down near $24^\circ N$. On the flip side, the border with Canada is famously defined by the 49th parallel ($49^\circ N$). If you're standing in Seattle, you’re much closer to the North Pole than someone sunbathing in Miami. It seems obvious, but seeing it on a grid puts the sheer scale of the continent into perspective.

Longitude is even wider. We span from about $67^\circ W$ in Maine all the way over to $124^\circ W$ in California. That’s a massive horizontal stretch. It’s why we have four different time zones just in the main block of states. Every 15 degrees of longitude roughly equates to one hour of time difference because that's how fast the Earth rotates relative to the sun.

📖 Related: Light Bulb Electrical Symbol: Why You’re Probably Reading the Diagram Wrong

The Weird Outliers: Alaska and Hawaii

Alaska is the ultimate map-breaker. It reaches so far north it hits $71^\circ N$. But even crazier? It stretches so far west into the Aleutian Islands that it actually crosses the 180th meridian. Technically, parts of Alaska are in the Eastern Hemisphere. So, if you’re looking at a truly accurate latitude longitude US map, Alaska makes the "West" rule a bit messy.

Hawaii is our southern anchor, sitting way down at roughly $19^\circ N$ to $22^\circ N$. It’s closer to the Equator than it is to any other US state. This isolation is why the coordinates for Honolulu look so different from anything in the mainland.

How to Read Coordinates Without a Degree in Cartography

You’ve probably seen coordinates written in a few different ways. It’s annoying. Why can’t we just pick one? Well, different professions have different needs.

- DMS (Degrees, Minutes, Seconds): This is the old-school way. $34^\circ 03' 08'' N$. It’s very nautical. It feels like something a sea captain would bark out.

- DD (Decimal Degrees): This is what your phone uses. $34.0522^\circ N$. It’s much easier for computers to calculate.

To understand the scale, remember this: one degree of latitude is roughly 69 miles (111 kilometers).

A "minute" is 1/60th of that—about 1.15 miles.

A "second" is about 100 feet.

So, if you’re looking at a map and you change the coordinate by just one second, you’ve moved about the length of a basketball court. That’s the kind of precision we’re talking about.

Finding the "Center" of the US

People love to argue about where the middle of the country is. If you go by the geographic center of the contiguous United States, you’ll end up near Lebanon, Kansas. The coordinates are roughly $39^\circ 50' N, 98^\circ 35' W$. There’s actually a little monument there.

But if you include Alaska and Hawaii? The center jumps over to South Dakota. Specifically, near a town called Belle Fourche. Maps are all about context.

Practical Uses: Why You Should Care

Why does this matter in 2026? Because technology fails.

I was hiking in the Ozarks a few years ago. My phone’s "pretty" map app wouldn't load because I had zero bars. But the GPS chip—which works independently of cell towers—could still give me my raw coordinates. Because I had a paper map with a latitude and longitude grid (a USGS topo map), I could plot exactly where I was.

It’s a safety skill.

- Geocaching: This is a global treasure hunt using coordinates. You put in a latitude and longitude, and you find a hidden box. It’s a great way to practice map reading.

- Precision Agriculture: Farmers use these maps to guide tractors within centimeters. They aren't just driving; they’re following a digital grid to save on fertilizer and fuel.

- Real Estate: Property lines are often defined by these coordinates in legal descriptions.

Common Misconceptions About US Maps

One thing that drives cartographers crazy is the "flat map" problem. The Earth is a sphere (well, an oblate spheroid, but let's not get pedantic). When you try to flatten that onto a piece of paper or a screen, things get stretched.

This is called projection.

The most common one, the Mercator projection, makes Greenland look as big as Africa. On a latitude longitude US map using Mercator, the northern states look way bigger than the southern ones. In reality, Texas is still massive, but on some maps, it looks strangely dwarfed by a stretched-out Montana. Always check what projection your map is using if you’re trying to judge actual size.

Actionable Steps for Mastering the Grid

If you want to move beyond just looking at a picture and actually understanding the data, here is how you do it.

Step 1: Check your settings. Open Google Maps or Apple Maps on your desktop or phone. In Google, you can right-click any spot to see the exact decimal degrees. Practice doing this for your house, your office, and your favorite park. Notice how the first number (latitude) gets bigger as you go north and the second number (longitude) gets "larger" (more negative) as you go west.

Step 2: Get a physical USGS Topo Map. Go to the US Geological Survey website. You can download PDF versions of topographic maps for your specific area. These maps have the latitude and longitude marked clearly along the edges (the "neatline").

Step 3: Learn the "Rule of 69." Remember that 1 degree $\approx$ 69 miles. If you’re looking at two cities and one is at $40^\circ N$ and the other is at $41^\circ N$, you know they are roughly 70 miles apart north-to-south. It’s a great way to "eye-ball" distances without a ruler.

Step 4: Use a Coordinate Converter. If you find an old map with Degrees/Minutes/Seconds, use a tool like NOAA’s coordinate converter to turn it into decimal degrees. This makes it searchable in modern apps.

Maps aren't just pictures. They are math. The next time you look at a latitude longitude US map, don't just see lines. See the grid that keeps our world organized. Whether you're tracking a storm, planning a cross-country flight, or just trying to find a cool campsite, those numbers are your best friends.

Start by finding the coordinates of the most remote place you’ve ever been. It’s a fun way to realize just how small—and how precisely mapped—our world really is.