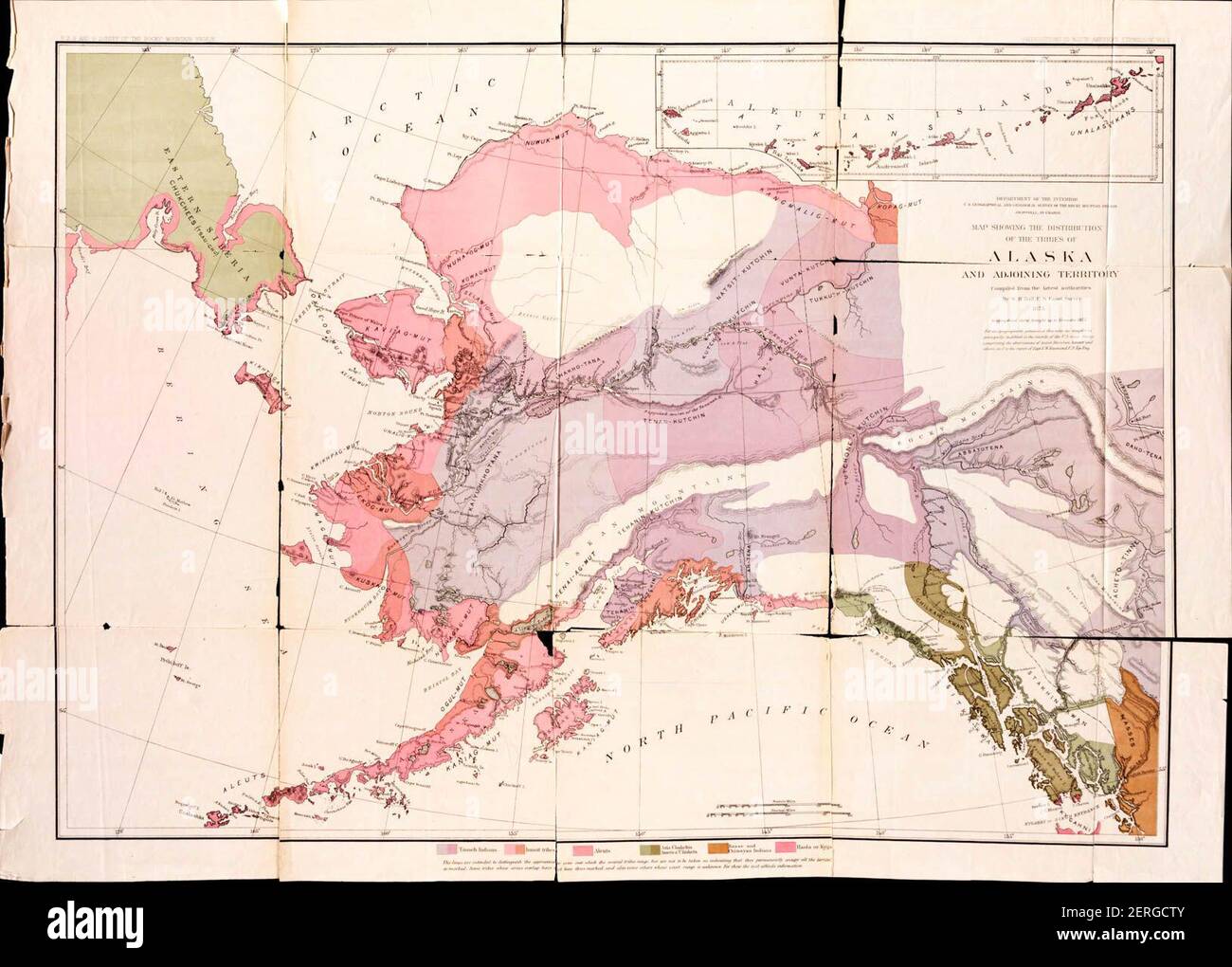

If you look at a standard map of Alaska, you see a lot of white space, some jagged blue coastlines, and maybe a few thin red lines representing the very limited highway system. It looks empty. Honestly, that is the biggest lie in American geography. When you pull up an alaska native tribes map, the "Last Frontier" suddenly gets crowded. It transforms from a desolate wilderness into a vibrant, overlapping patchwork of cultures that have been there for roughly 10,000 years.

Most people expect to see a few neat lines dividing the state into tidy squares. It doesn't work like that. The reality of Indigenous Alaska is a messy, beautiful, and sometimes confusing mix of linguistic boundaries, ancestral hunting grounds, and modern legal corporations. You can't just draw a circle around Anchorage and call it a day.

The Five Main Groups You Need to Know

Before you get lost in the hundreds of individual village names, you have to understand the big picture. Alaska is generally split into five major cultural regions. The Inupiat and St. Lawrence Island Yupik hold down the fort in the north and northwest. Down in the southwest, you’ve got the Central Yup’ik and Cup’ik. The interior—that massive, freezing heart of the state—is the domain of the Athabascan people. Then you have the Aleut (Unangax̂) and Alutiiq (Sugpiaq) along the chain and the southern coast. Finally, the Southeast "panhandle" is home to the Eyak, Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian.

It’s easy to think of these as just "tribes," but they are distinct nations. An Athabascan person from the dry, sub-zero interior has a lifestyle, language, and history that is worlds apart from a Tlingit person living in the temperate, rainy rainforests of the south. They are as different as a person from Norway is from a person from Italy.

Why the Lines Blur

The tricky thing about an alaska native tribes map is that borders were never static. These were—and many still are—subsistence cultures. People moved where the food was. If the caribou shifted their migration, the people moved. If the salmon run failed in one river, families navigated to another. Mapping these boundaries is like trying to map the wind.

The ANCSA Revolution: Mapping by Money and Land

In 1971, the map changed forever. The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) was signed, and it did something no other treaty in U.S. history had done. It did away with the "reservation" model used in the Lower 48 (with one exception, Metlakatla). Instead, it divided Alaska into 12 distinct geographic regions, each represented by a Native Regional Corporation.

👉 See also: Why the Southern Region of Brazil Feels Like a Different Country

This created a whole new kind of map.

Now, when you look at an alaska native tribes map, you are often seeing these corporate boundaries:

- Arctic Slope Regional Corporation (ASRC) in the far north.

- Doyon, Limited covering the massive interior.

- Sealaska in the southeast.

- Calista in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta.

It’s a corporate-legal geography that sits right on top of the ancestral one. It’s weird, right? But these corporations are the economic engines of their regions. They own the land, they manage the resources, and they provide scholarships and benefits to their shareholders, who are the tribal members themselves.

Common Misconceptions About the Map

People usually get two things very wrong. First, they think every "Native" person in Alaska is an "Eskimo." That word is largely considered outdated and even offensive to many, especially in the eastern Arctic. More importantly, it’s inaccurate. An Athabascan person is not Inupiat. They aren't even closely related linguistically.

Second, people assume that because a village is on the map, there must be a road to it. Nope.

Most of the 229 federally recognized tribes in Alaska are in "off-road" communities. If you want to visit a tribe in the Calista region, you aren't driving. You are taking a bush plane or a boat. This physical isolation is why the alaska native tribes map has remained so culturally distinct. When you can't just drive to a Walmart, your connection to the land and your local community stays incredibly tight.

The Power of Place Names

One of the coolest things happening right now in Alaskan cartography is the "re-mapping" of the state using traditional place names. For a century, the map was covered in the names of British explorers or Russian fur traders who were just passing through.

Take "Mount McKinley." Everyone calls it Denali now. That’s a Koyukon Athabascan word meaning "The Tall One." But this is happening on a smaller scale everywhere. In the Bristol Bay region, maps are being updated to reflect names that describe what the land actually does—places named "where the berries are thick" or "water that never freezes."

These maps aren't just about labels; they are about reclaiming history. When you look at an alaska native tribes map that uses Indigenous names, you're seeing a manual for survival. The names tell you where to find water, where the ice is dangerous, and where the spirits live.

📖 Related: Fargo’s BBQ in Bryan, Texas: Why the Best Ribs in the State Are Tucked Away in a Small Blue Building

The Modern Conflict

It isn't all just history and heritage. Mapping tribes is a political act. There are ongoing debates about "Tribal Sovereignty" versus "State Authority." Because the land is owned by corporations and not "held in trust" by the federal government like reservations are, the legal map of Alaska is a constant battleground.

Who has the right to regulate fishing on the Kuskokwim River? The State of Alaska says they do. The local tribes say the river has been theirs since before the United States was even a concept. When you look at the map, you’re looking at a live legal dispute.

How to Use a Tribe Map Respectfully

If you are traveling to Alaska or just researching, don't just treat the alaska native tribes map as a checklist of places to go.

- Understand land ownership. Just because it looks like "open wilderness" doesn't mean it is. It likely belongs to a village or regional corporation. Trespassing is a real issue.

- Learn the greeting. If you’re in the Doyon region, learn an Athabascan greeting. If you're in the Arctic, learn an Inupiaq one. It goes a long way.

- Support local. If you use a map to find a village, look for local artists or guides. Buy a carved walrus ivory piece or a beaded high-bush cranberry design directly from the maker.

The Map is Always Changing

The most important thing to remember is that these cultures aren't museum pieces. They are evolving. There are Tlingit TikTokers and Inupiat tech entrepreneurs. The map is a living document. Climate change is even physically altering the map; as permafrost melts and coastlines erode, some ancestral villages like Shishmaref are literally being forced to move their entire community.

📖 Related: Currency Converter Icelandic Krona to USD: What Most Travelers Get Wrong

When you look at the alaska native tribes map, you aren't looking at the past. You are looking at a blueprint for how to live in one of the harshest environments on Earth. It’s about resilience.

Actionable Insights for Your Search

- Consult Official Sources: For the most accurate current boundaries, use the Alaska Federation of Natives (AFN) resources or the National Park Service's tribal heritage maps.

- Check the Language Map: The Alaska Native Language Center at the University of Alaska Fairbanks provides the best map for understanding where different dialects start and end.

- Acknowledge the Land: If you are a content creator or traveler, use the Native Land Digital tool (native-land.ca) to identify whose ancestral territory you are standing on, but verify it with local tribal council websites as digital tools can sometimes be imprecise.

- Respect Privacy: Many tribal lands require permits for photography, hunting, or camping. Always contact the local Village Corporation office before planning a trip off the beaten path.

The map of Alaska is more than just geography; it is a story of survival, law, and identity that continues to be written every day.