You look at a modern map of South Asia and you see borders. Lines. Fences. But 4,500 years ago, if you were holding a map of ancient Indus River Valley, those lines would vanish. Instead, you'd see a massive, sprawling network of blue veins—the rivers—and dots representing some of the most sophisticated urban planning the world had ever seen. Honestly, it’s kind of wild to think that while people in other parts of the world were struggling to figure out basic drainage, the folks in the Indus Valley were living in cities with grid systems that would make a modern civil engineer weep with joy.

The Indus River is the heartbeat here. It starts high up in the Himalayas and snakes down through what is now Pakistan and northwest India. It's not just one river, though. We’re talking about the "Land of Five Rivers" (the Punjab) and the now-lost Saraswati River, which many archaeologists like Jane McIntosh believe played a huge role in where these people decided to settle. When you look at the map of ancient Indus River Valley, you aren't just looking at geography. You’re looking at a blueprint for survival in a flood-prone, fertile, and often unpredictable landscape.

Where Exactly Was This Place?

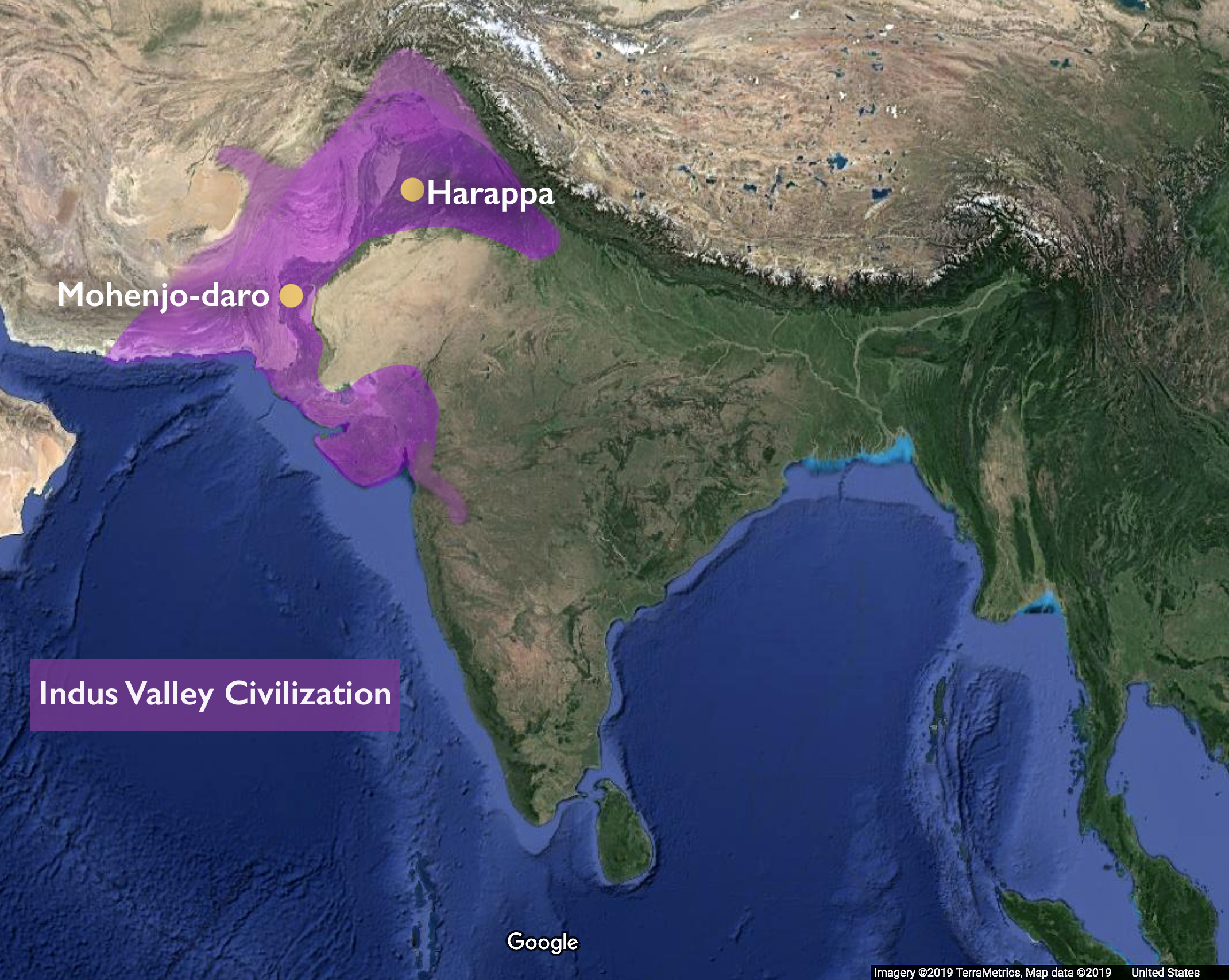

People get confused. They think it was just a tiny spot near a river. Nope. The Bronze Age Indus Civilization—or the Harappan Civilization—covered more ground than ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia combined. Seriously. We are talking about over a million square kilometers.

If you trace the map of ancient Indus River Valley today, it stretches from northeast Afghanistan down through Pakistan and into western India. The northernmost point is usually cited as Shortughai (an ancient trading outpost), while the southernmost reaches go all the way down to Gujarat, specifically places like Lothal.

👉 See also: What is the Time in Yemen Now? Why This Ancient Land Never Changes Its Clocks

Why there?

Basically, it was all about the silt. The annual flooding of the Indus deposited incredibly rich soil. This meant farmers could grow enough surplus grain to feed thousands of people who weren't farmers—priests, bead-makers, seal-carvers, and traders. Without that specific geography, the civilization never would have happened. It’s that simple.

The Major Hubs You Need to Know

Most people can name Harappa and Mohenjo-daro. They’re the "Big Two." But the map is actually dotted with over 1,000 known sites.

Mohenjo-daro, located in the Sindh province of Pakistan, is arguably the most famous. It means "Mound of the Dead," which is a bit grim, but the city itself was anything but. It had a "Citadel" and a "Lower Town." It had the Great Bath, which sort of looks like a communal swimming pool but was likely used for ritual purification.

Then there's Harappa, further north in the Punjab. It’s the namesake of the whole culture. Harappa was huge, but sadly, a lot of its bricks were carted off in the 19th century to be used as ballast for a railway line. Yes, literal ancient history was ground up to support British trains. It’s a tragedy, really.

But don't ignore the outskirts. Look at Dholavira in the Rann of Kutch. The map of ancient Indus River Valley shows this site in a salt marsh. How did they survive? They were masters of water management. They built massive stone-cut reservoirs to catch every drop of monsoon rain. It was brilliant.

How the Map Dictated Trade

Trade wasn't an afterthought. It was the engine.

When you study the map of ancient Indus River Valley, you see it’s perfectly positioned for international commerce. To the west, you have the Persian Gulf. To the north, the mineral-rich mountains.

We know they were trading with Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq). Archaeologists have found Indus seals—those little soapstone squares with animal carvings—in cities like Ur and Kish. The Mesopotamians called the Indus region "Meluhha."

- Lapis Lazuli: Came from the mines in Afghanistan.

- Carnelian: Those bright orange beads were a specialty of the Gujarat region.

- Copper: Sourced from the Khetri mines in Rajasthan.

- Timber: Floated down the rivers from the Himalayas.

The rivers were the highways. It’s way easier to float a ton of cedar wood down a river than to haul it across a desert on a cart with solid wooden wheels. The map of ancient Indus River Valley is essentially a map of 4,000-year-old shipping lanes.

The Mystery of the "Lost" River

You can't talk about the Indus map without mentioning the Ghaggar-Hakra river system. Many scholars, including those like Michel Danino, argue this was the Vedic Saraswati River.

If you look at a satellite map today, you see a dry bed. But back then? It was a perennial river that supported hundreds of settlements. In fact, there are actually more sites along this dry bed than along the Indus itself.

This changes the whole "Indus Valley" narrative. Some people prefer the term "Indus-Saraswati Civilization" because it more accurately reflects the geographical reality of where people actually lived. When that river dried up—likely due to tectonic shifts or climate change—the map broke. People moved. The cities were abandoned. The "Great Tradition" started to fragment into smaller, local cultures.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Map

There’s this misconception that the Indus people were a single, unified empire with one king. The map doesn't really support that.

There are no massive palaces. No giant statues of "Great Leaders." No depictions of war or conquered enemies.

Instead, the map of ancient Indus River Valley shows a series of highly standardized but potentially independent city-states. It’s weird. The bricks in Harappa are the same size as the bricks in Mohenjo-daro, hundreds of miles away. The weights and measures are the same. How do you get that kind of uniformity without a central government? Maybe it was a trade confederation? Or a shared religious identity? We still don't know because we haven't cracked their script yet.

Another big error? Thinking the map stayed the same. Rivers move. The Indus is notorious for "avulsion"—that's a fancy word for when a river suddenly decides to change its course. Imagine waking up and your harbor is now five miles away from the water. That happened. It forced the Indus people to be incredibly mobile and adaptable.

💡 You might also like: World 7 Continents Map: Why Your Geography Teacher Might Have Lied to You

The Infrastructure on the Map

The level of detail in their urban planning is sort of mind-blowing.

- Grid Systems: These weren't winding medieval alleys. The streets were laid out in north-south and east-west grids.

- Drainage: Every house had a bathroom. The waste flowed into covered street drains. This is stuff Europe didn't figure out again until the 1800s.

- Standardized Bricks: They used baked bricks in a 4:2:1 ratio. This makes for incredibly stable walls.

When you look at a site plan—a micro-map of an Indus city—you see a clear separation between the public "Citadel" area (elevated for flood protection) and the residential quarters. It shows a society that valued order, hygiene, and community over individual ego.

Climate Change and the Disappearing Map

Eventually, the map of ancient Indus River Valley started to fade. Around 1900 BCE, the "Mature Harappan" phase ended.

It wasn't a sudden invasion by "Aryans" as older textbooks used to claim. That theory has been largely debunked by modern DNA studies and lack of archaeological evidence for a massive war. Instead, it was likely a "death by a thousand cuts."

The monsoons shifted. The rivers dried up or flooded too violently. The trade with Mesopotamia collapsed. People didn't just vanish; they moved east and south. They became the ancestors of the people living in India and Pakistan today. The map changed from a focused urban powerhouse to a scattered rural landscape.

How to Explore This Today

If you want to "see" the map of ancient Indus River Valley in person, it’s a bit of a trek, but totally worth it.

In Pakistan

Mohenjo-daro is a UNESCO World Heritage site. You can walk through the excavated streets. You can stand in the Great Bath. It’s hauntingly quiet. Harappa is also accessible, though as mentioned, it’s more "ruined" than Mohenjo-daro.

In India

Rakhigarhi in Haryana is currently one of the biggest excavation projects. It’s actually larger than Mohenjo-daro. Then there’s Lothal in Gujarat, where you can see the world’s first man-made dock. It’s a coastal town that shows just how far their maritime reach went.

Actionable Insights for the History Buff

If you're trying to wrap your head around this ancient world, don't just look at a flat image. Use these steps to truly understand the geography:

- Overlay Satellite Imagery: Use Google Earth to look at the "palaeochannels" (old river beds) in the Thar Desert. You can actually see where the rivers used to flow.

- Compare the Bricks: If you visit a museum (like the National Museum in New Delhi), look at the bricks. Note the 4:2:1 ratio. It's the "DNA" of the Indus map.

- Follow the Trade Routes: Look at a map of the Indian Ocean. Realize that Indus sailors were hugging the coast all the way to the Oman peninsula.

- Study the Rainfall: Check out a monsoon map. You'll see that the Indus civilization existed right on the edge of the monsoon's reach. A slight shift in rain meant the difference between a golden age and a famine.

The map of ancient Indus River Valley is more than just dots and lines. It's a story of how humans tried to tame a wild river system, built the world's first "smart cities," and eventually had to bow to the power of a changing climate. It’s a lesson in humility, honestly. We think we’re so advanced, but those people were building sewer systems and global trade networks 4,500 years ago without a single computer or a drop of oil.

To get the most out of your research, start by looking at the major river junctions. Focus on the sites of Kalibangan, Banawali, and Ganweriwala. These sites bridge the gap between the Indus and the Saraswati, providing the clearest picture of how this massive civilization functioned as a cohesive whole. Examine the topography of the Bolan Pass; it was the gateway for all land-based trade toward Central Asia. By understanding the physical constraints of the mountains and the shifting nature of the silt-heavy rivers, the layout of these ancient cities finally starts to make perfect sense.