Maps are weird. You look at a Cascades mountain range map and see a bunch of green squiggles and brown ridges stretching from British Columbia down into Northern California. It looks static. But if you’ve ever stood at the base of Mount Rainier or tried to navigate the North Cascades Highway in a shoulder-season snowstorm, you know those lines on the paper are actually lying to you—or at least, they aren't telling the whole story.

The Cascades aren't just one long pile of rocks.

They are a 700-mile volcanic arc. Most people think "Cascades" and they picture the "Big Ice" peaks—the volcanoes. You know the ones: Baker, Rainier, St. Helens, Hood, Shasta. But look closer at a topographic map and you’ll see the "High Cascades" are actually perched on top of a much older, more eroded base called the "North Cascades" or the "Western Cascades." It’s basically a geological layer cake that most travelers completely misunderstand.

Why the Cascades Mountain Range Map is Split in Two

Geologists like those at the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) split this range into distinct provinces. If you’re looking at a map of Washington State, the northern half looks like a chaotic mess of jagged teeth. That’s because the North Cascades are non-volcanic. They’re made of ancient, uplifted metamorphic rock. Think of it as "North American Alps."

Then, south of roughly Snoqualmie Pass, the map changes.

The peaks get spaced out. They become solitary giants. This is the "High Cascades" region. When you're driving I-5, you see these massive white pyramids standing alone. These are the young volcanoes, most of which have popped up in just the last 1.6 million years. It’s a blip in Earth’s history.

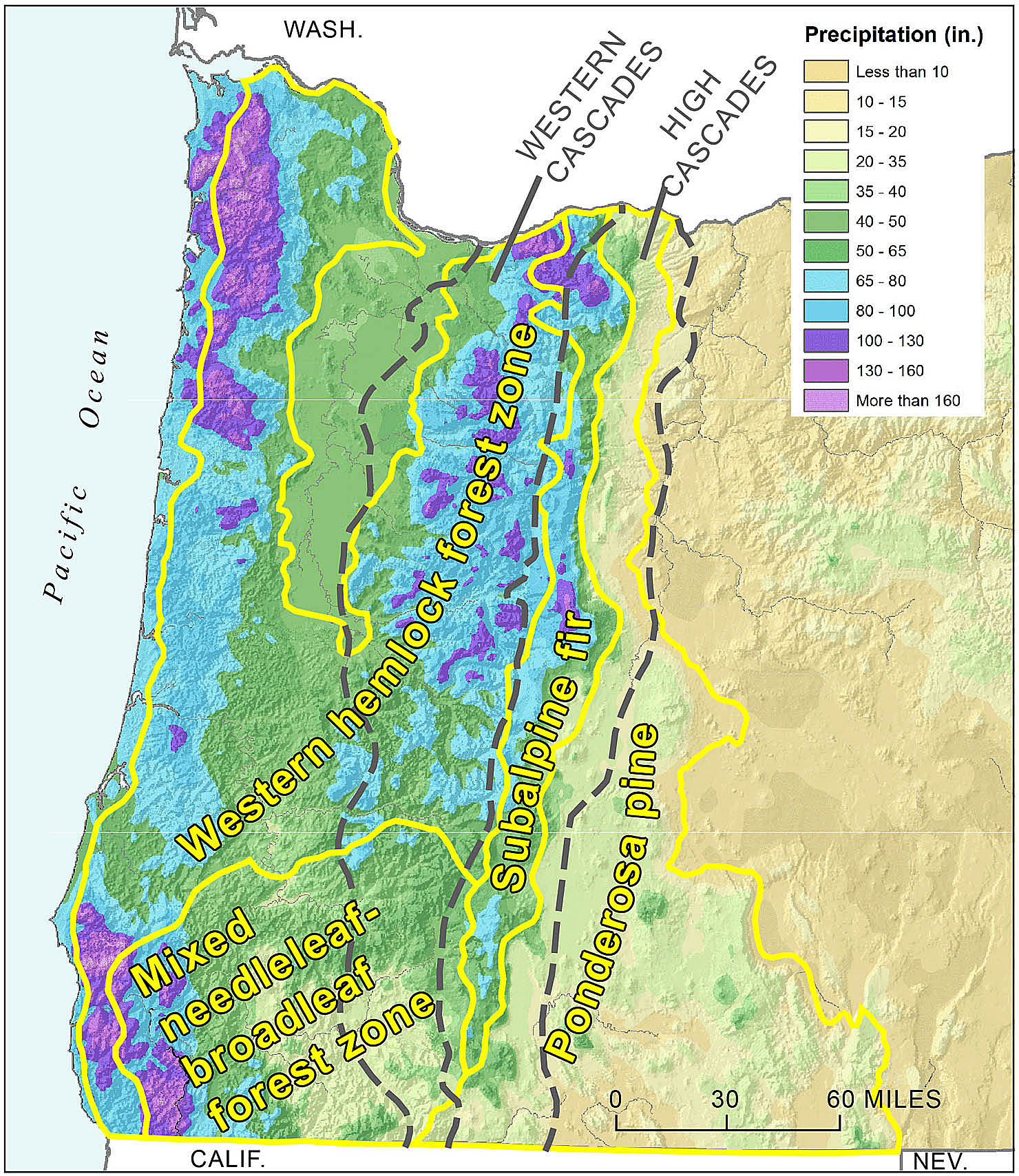

Honestly, the way we map these mountains often ignores the rain shadow. If you look at a vegetation-overlay map, you’ll see a brutal divide. The west side is a dripping, mossy jungle of Douglas fir and Western Red Cedar. Cross the crest—literally a line on your map—and within ten miles, you’re in dry Ponderosa pine territory. It’s one of the most dramatic climatic shifts on the planet, and it's all because of how this specific range catches moisture from the Pacific.

Navigating the "Thru-Hike" Reality

If you’re planning a trip, you’re probably looking at the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT). It follows the spine of the Cascades for a massive chunk of its length.

But here’s the thing about a digital Cascades mountain range map versus reality: snow.

In a heavy year, places like Mount Baker or Paradise at Mount Rainier can hold 50 or 60 feet of cumulative snowfall. On a map, a trail looks like a simple two-mile loop. In June, that "simple" trail might be under twelve feet of consolidated ice. People get in trouble because they trust the line on the screen more than the reality of the elevation.

- North Cascades: High-alpine, incredibly steep, very few roads. It's the most "wilderness" part of the lower 48.

- Central Cascades: Think the Alpine Lakes Wilderness. High demand, permits required (The Enchantments, anyone?), and heavy foot traffic from Seattle and Portland.

- Southern Cascades: Volcanic craters, lava tubes, and flatter plateaus between the big peaks.

I’ve spent weeks wandering through the Pasayten Wilderness near the Canadian border. Up there, the map is your best friend and your worst enemy. There are trails on the official Forest Service maps that haven't been maintained since the 1970s. You see a dotted line, you think "easy day," and then you spend six hours bushwhacking through slide alder because a wildfire five years ago wiped out the path.

The Volcanic Hazards You Won't See on a Standard Map

If you grab a standard tourist map, you’ll see campgrounds and vista points. What you won't see are the lahar zones.

A lahar is basically a volcanic mudslide with the consistency of wet concrete moving at 40 miles per hour. The Washington Department of Natural Resources has specific maps showing where these would go if Rainier or Adams decided to wake up. Towns like Orting and Puyallup are built directly on top of ancient lahar deposits.

It’s a weird vibe. You’re hiking in this beautiful, serene forest, but the ground beneath you is literally debris from a mountain that fell apart 500 years ago.

And then there's the "Rainier Shadow."

👉 See also: World Map Thailand and India: Why They’re Way Closer Than You Think

Most people don't realize that Mount Rainier is so massive it creates its own weather. It can be a clear day in Seattle, but Rainier might be wrapped in a "lenticular cloud"—it looks like a UFO sitting on the summit. If you see that on your horizon, the "map" for your hike just changed. High winds and moisture are hitting the peak, and it’s about to get nasty.

Where to Get the "Good" Maps

Don't just rely on Google Maps. It’s great for finding a Starbucks, but it’s terrible for the Cascades.

If you’re actually going into the woods, you need Green Trails Maps. They’re the gold standard for PNW hikers. They show the tiny creek crossings and the actual switchbacks that digital apps often smooth over.

Also, look into CalTopo. It’s a tool used by Search and Rescue teams. You can layer "Slope Angle Shading" over a Cascades mountain range map to see exactly where the terrain gets too steep for comfort. If you see deep purple or red on that slope shading, you’re looking at avalanche terrain or cliffs.

The Cascades Experience: Real Talk

Look, the Cascades are rugged.

They aren't the rolling hills of the Appalachians. They aren't the dry, high-altitude desert of the Southern Rockies. They are wet, steep, and covered in some of the densest biomass on Earth. If you stay on the main roads—Highway 20, Stevens Pass (Hwy 2), or Snoqualmie (I-90)—you get a "highlights reel."

💡 You might also like: The TD Five Boro Bike Tour: What Most People Get Wrong

But the real Cascades?

They're found in the "dead zones" on the map where the roads don't go. Like the Glacier Peak Wilderness. It’s one of the most remote places in the US. You have to hike for days just to see the mountain because it’s tucked so far back into the folds of the range.

Most people make the mistake of over-scheduling. They see three peaks on a map and think they can hit them all in a weekend. In the Cascades, 10 miles can take you all day if there’s 4,000 feet of vertical gain involved. And there usually is.

Practical Steps for Your Next Trip

Before you head out, do these three things. They’ll save your life, or at least your weekend.

Check the SNOTEL data. This is a network of automated sensors that tells you exactly how much snow is on the ground at specific elevations. If the map says you're going to 5,000 feet, and SNOTEL says there's 40 inches of "Snow Water Equivalent" at 4,800 feet, bring your snowshoes. Or go to the beach instead.

Download your maps for offline use. There is zero cell service in about 80% of the Cascade range. If you're relying on a live connection, you're going to end up as a "missing person" headline. Use Gaia GPS or AllTrails+ and download the layers before you leave your driveway.

Check the smoke maps. In July and August, the Cascades are a tinderbox. Use the AirNow Fire and Smoke Map. A perfectly planned trip to North Cascades National Park is useless if the visibility is 50 feet and your lungs are burning from a fire in British Columbia.

The Cascades are one of the last truly wild places where the map is just a suggestion. The terrain is constantly shifting—glaciers are melting, riverbeds are moving after winter floods, and new trails are being cut while old ones vanish into the brush. Treat the map as a guide, but always keep your eyes on the actual horizon.