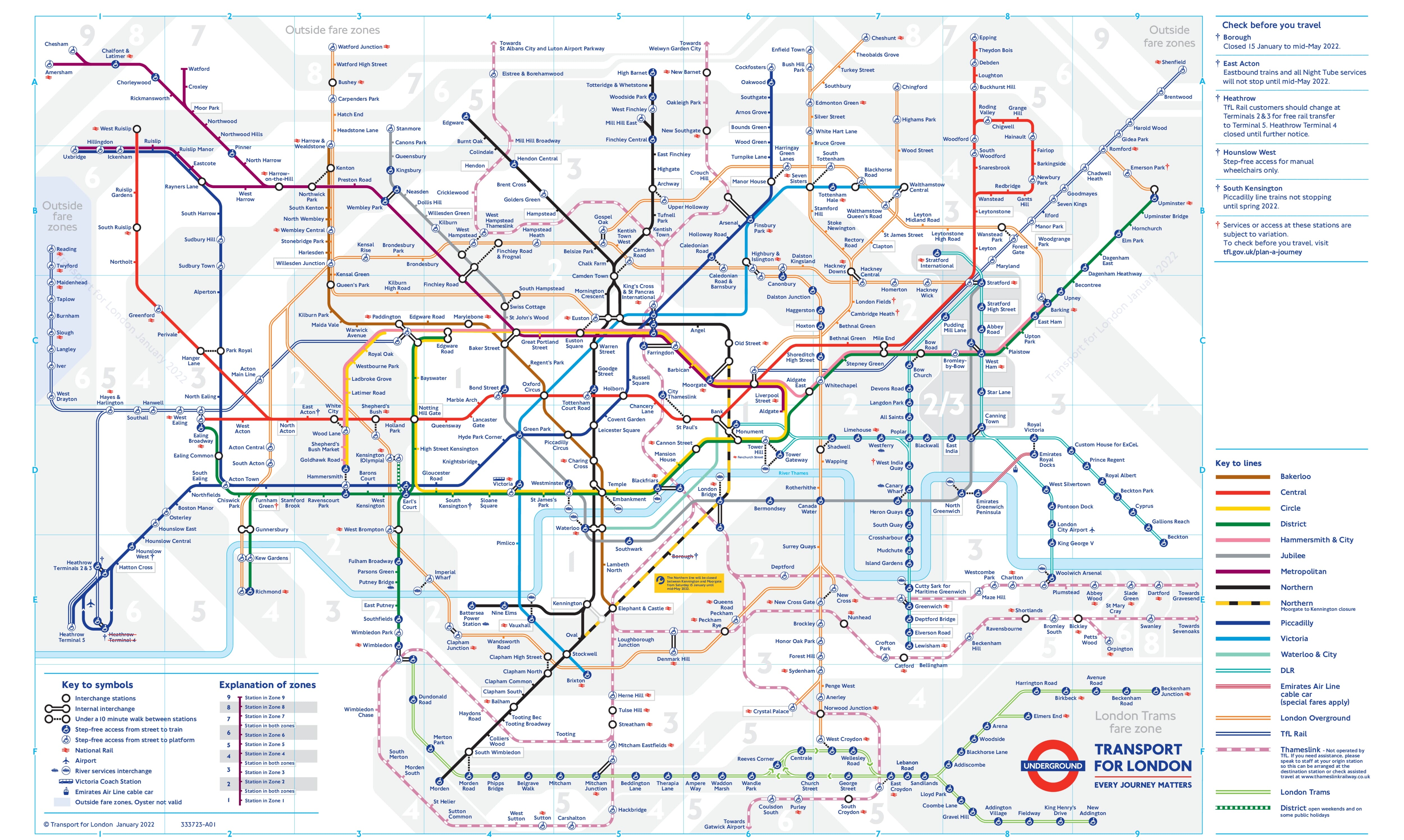

You're standing at Leicester Square. You want to get to Covent Garden. Naturally, you pull up the tube in London map on your phone, see the different colored lines, and figure you should hop on the Piccadilly line for one stop. It’s the logical thing to do, right?

Wrong.

If you do that, you’ve just spent £2.80 and about fifteen minutes of your life—including the deep descent into the station and the wait on the platform—to travel 260 meters. You could have walked it in four minutes. This is the fundamental paradox of the iconic London Underground map. It is a masterpiece of design, a global cultural icon, and, for the unsuspecting pedestrian, a total geographical lie. It wasn't built to show you where things are. It was built to show you how they connect.

The Lie That Makes Sense

Harry Beck, a technical draftsman, changed the world in 1933. Before him, the tube in London map was a messy, sprawling spiderweb of lines overlaid on a real geographic map. It was cluttered. It was confusing because the central stations were all squashed together while the outer stations were miles apart. Beck realized that when you're underground, you don't care if you're under Oxford Street or Mayfair. You just want to know which station comes next and where to change lines.

He treated the map like an electrical circuit diagram.

By using only vertical, horizontal, and 45-degree diagonal lines, Beck created a "topological" map. This means the distances between stations on the paper have zero relationship to the distances on the ground. This is why the map looks so clean and organized, but it’s also why tourists end up exhausted. When you look at the map, the gap between Paddington and Lancaster Gate looks massive. In reality? It's a five-minute stroll through a nice neighborhood.

The map is a mental model, not a GPS. Honestly, if we tried to use a geographically accurate map today, the center of London would be an illegible ink blot of overlapping text, while the ends of the Metropolitan line would require a fold-out sheet the size of a dinner table.

The Secret Layers of the Underground

The map you see on the platform walls isn't the only one that exists. Transport for London (TfL) actually produces several versions that most people never bother to find. There is a walking distance map. There is a "steps-free" map for those with strollers or wheelchairs. There is even a map that shows how many calories you burn walking between stations.

Most people don't realize how much the tube in London map hides the sheer depth of the system. Take the Northern Line. It’s not actually one line; it’s a complex "X" shape with two different branches through the city center. If you’re at Euston and want to go to Bank, you have to be incredibly careful which platform you stand on, or you’ll end up in Charing Cross. It’s a mess. Even the colors are a bit of a psychological trick. We associate the Central line with a bright, energetic red, but anyone who has been on it in mid-July knows it should probably be colored "Subterranean Oven Orange."

The Elizabeth Line and the Map Expansion

The newest addition, the Elizabeth line (the purple one), threw a massive wrench into the map's design. Because it's a high-speed railway rather than a traditional "tube," it covers massive distances. Integrating it into the classic Beck-style layout was a nightmare for designers. It forced the map to stretch. Suddenly, places like Abbey Wood and Reading had to fit into a visual language designed for the 1930s.

It’s getting crowded. Some critics, like those at the London Transport Museum, argue the map is reaching a breaking point where it becomes too complex to be useful at a glance. You've got the Overground (orange), the DLR (turquoise), the Tramlink, and now the various "windrush" and "weaver" branches of the Overground being given their own distinct colors and names.

Why the Map Fails the "West End Test"

If you are trying to navigate the West End using just the tube in London map, you are going to lose time. This is the biggest mistake locals see tourists make every single day.

- Charing Cross to Embankment: On the map, they look like separate hubs. In real life, they are practically the same building. You can see one from the entrance of the other.

- Knightsbridge to South Kensington: A lovely walk past museums. On the tube? A sweaty, crowded ride that takes longer.

- The Canary Wharf Maze: This is a big one. The DLR station and the Jubilee line station at Canary Wharf are not the same place. The map makes them look like a simple interchange, but you actually have to go up, walk through a shopping mall, and go back down.

Understanding these nuances is what separates a "Londoner" from someone who is clearly lost. The map is a suggestion, not a rulebook.

The Politics of the Map

It sounds weird, but what gets put on the tube in London map is a massive political and economic issue. When a station is added to the map, property values in that area skyrocket. This is why developers fought so hard for the Battersea Power Station extension on the Northern Line.

📖 Related: Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception Denver: What Most People Get Wrong About This Landmark

There's also the "Zone 1" prestige. For years, stations like Shoreditch High Street were technically in Zone 2, but were moved into "Zone 1/2" to make the area more attractive to commuters and businesses. The map isn't just a navigation tool; it's a tool of urban engineering and gentrification. When you look at that colorful grid, you're looking at a map of London's wealth and infrastructure priorities.

Tips for Mastering the Grid

Don't just stare at the map. Use it with context.

First, always check the "walking" version of the map if you're in the center. TfL publishes a map specifically showing which stations are within a 10-minute walk of each other. It will save you a fortune in fares.

Second, understand the "out of station interchange" (OSI). This is a secret rule where you can touch out of one station and touch into another nearby station within a certain timeframe (usually 10 to 20 minutes) without being charged for two separate journeys. The map doesn't always make these clear. For example, walking between Hackey Central and Hackney Downs is a valid interchange, but it’s just a dotted line on most versions of the map.

Third, look at the symbols. The little "wheelchair" icons are vital. Some stations are "step-free to train," while others are only "step-free to platform." If you have heavy luggage, that distinction is the difference between an easy trip and a literal nightmare of spiral staircases.

The Future of Navigating London

We are moving away from the paper map. With apps like Citymapper and Google Maps, the tube in London map is becoming more of a brand than a tool. We follow the blue dot on our screens now. But even then, the DNA of Harry Beck's design is everywhere. The way those apps display the lines—the specific shades of "Lucozade orange" for the Overground or "Busby blue" for the Victoria line—all stems from that 1933 breakthrough.

London is currently testing more "augmented reality" wayfinding. Imagine looking through your phone camera and seeing a glowing line on the pavement that leads you to the right platform. It sounds sci-fi, but it's already in beta in some larger stations like King's Cross. Even so, the classic map will stay. It's on t-shirts, mugs, and duvet covers for a reason. It’s the simplified version of a chaotic city that we all want to believe in.

Actionable Next Steps for Your Next Trip

Stop relying on the giant wall map for everything. Here is how to actually navigate like a pro:

- Download the "Walking Tube Map": Search for the official TfL PDF that shows walking times between stations. Use this for anything in Zone 1.

- Check for "Pink Card Readers": If you are traveling around the edge of London (not through Zone 1), look for pink readers at interchange stations like Highbury & Islington or Stratford. Touching these proves you didn't go through the center, often resulting in a much cheaper fare.

- Use the "Interchange" Secret: If you need to get from the Northern line to the Victoria line at Euston, follow the signs for the "interchange" rather than following the exit signs. There are hidden tunnels that cut the walk in half, but they aren't marked on the main maps.

- Ignore the "Next Train" Clock for a Minute: Look at the direction, not just the destination. On the Northern line, "Southbound" can mean two completely different parts of London depending on whether it's via Bank or via Charing Cross. Always check the platform screens twice.

The map is a beautiful piece of art. Use it to understand the connections, but use your feet to understand the city. London is much smaller than the map wants you to believe.