Manhattan is a grid. Well, mostly. If you’ve ever stood on the corner of 14th Street and 6th Avenue, you probably felt like you had the whole island figured out. Numbers go up as you walk north. Streets run east-west; avenues run north-south. Easy. But then you hit Greenwich Village, or you wander down toward Wall Street, and suddenly the Manhattan map New York looks less like a graph paper drawing and more like a spilled bowl of noodles.

It’s messy.

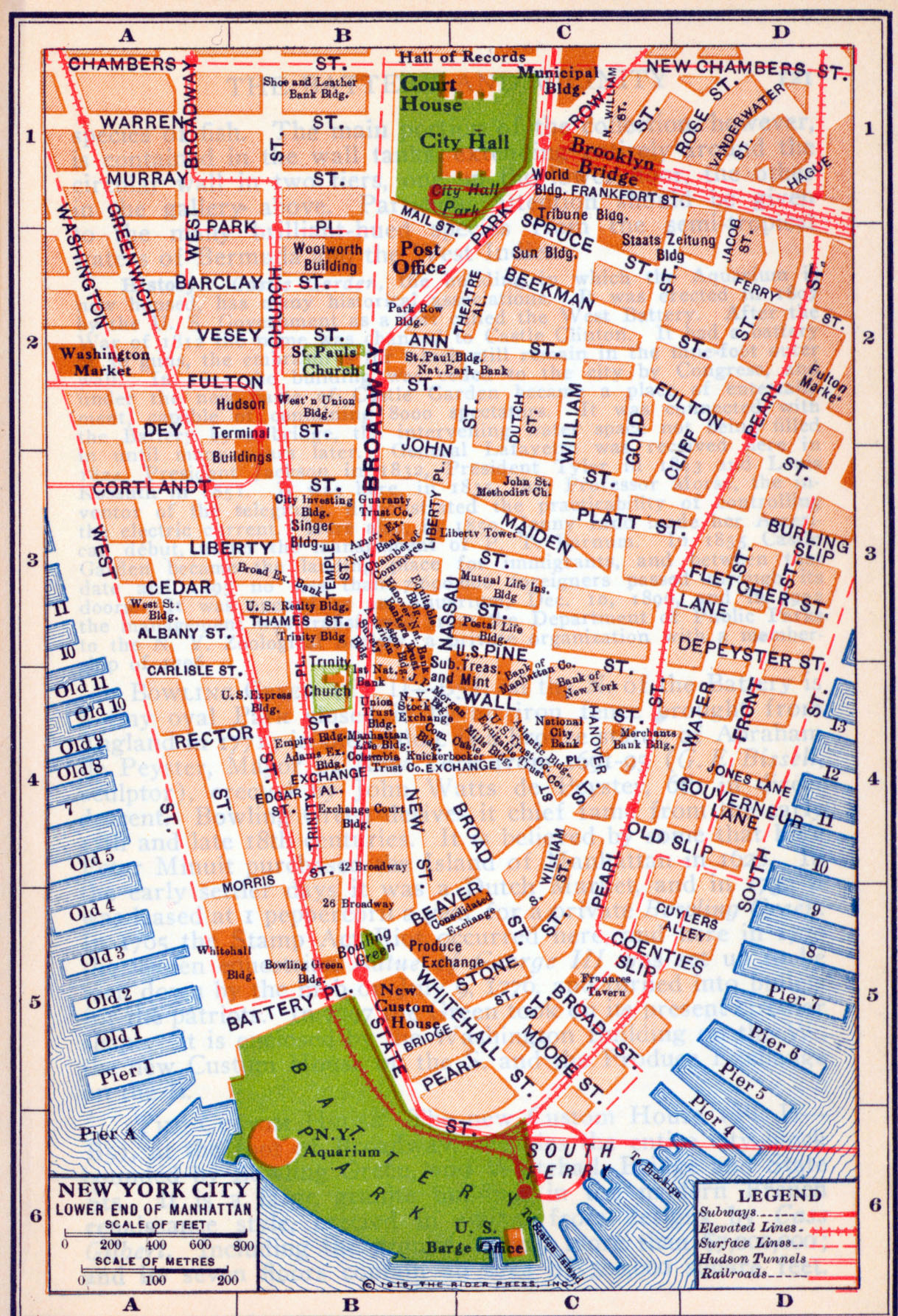

Honestly, even people who have lived here for a decade get turned around once the numbered streets disappear. You’ve got West 4th Street intersecting with West 10th Street. How does that even happen? It happens because the city wasn't always a planned masterpiece of urban efficiency. Before the famous Commissioners' Plan of 1811, Manhattan was a chaotic collection of farms, rolling hills, and narrow Dutch pathways. That history is still written into the pavement today, hiding in plain sight every time you open a navigation app.

The Grid vs. The Chaos: Deciphering the Manhattan Map New York

Most people think the grid is the soul of the city. In reality, the grid was a real estate play. In 1811, the city leaders basically said, "We need to sell lots, and rectangles are easier to sell than weird triangles." They flattened hills and buried streams to make it happen. But they couldn't quite erase the past.

Take Broadway. It's the ultimate rebel. It slices diagonally across the entire island, creating those iconic "bow-tie" intersections like Times Square and Union Square. If you look at a Manhattan map New York, Broadway is the only thing that feels organic because it follows an old Native American trail called Wickquasgeck. It ignores the 90-degree angles. It does its own thing.

📖 Related: Why Spa Ojai at the Ojai Valley Inn is Still the Gold Standard for California Wellness

Then you have the "Below 14th Street" problem. North of 14th, you’re safe. The numbers protect you. But south of there, you enter the older world. Places like Stuyvesant Street run at a weird angle because Petrus Stuyvesant wanted his front door to face true east, grid be damned. When you’re navigating Lower Manhattan, you aren't just looking at a map; you’re looking at 400 years of stubborn landowners refusing to move their fences.

Why Your GPS Might Be Lying to You

We rely on Google Maps or Apple Maps, but Manhattan is a nightmare for a phone's GPS chip. It's called the "Urban Canyon" effect. You’re walking down 42nd Street, surrounded by skyscrapers like the Chrysler Building or the Bank of America Tower, and your little blue dot starts jumping three blocks away.

The signals bounce off the glass and steel.

It’s frustrating.

You’ll be looking for a specific subway entrance, and the map says you’ve arrived, but you’re actually standing in front of a Halal cart with no stairs in sight. This is why understanding the "logic" of the Manhattan map New York is better than blindly following a screen.

- Avenues are wide. They usually have traffic lights timed for speed.

- Streets are narrower. Except for the big ones like 14th, 23rd, 34th, 42nd, 57th, and 125th. Those are two-way.

- Traffic flow alternates. Usually, even-numbered streets go east. Odd-numbered streets go west. It’s a simple rule that saves you from walking the wrong way for ten minutes.

The Secret Geography of the Neighborhoods

If you look at a standard tourist map, the neighborhoods look like neat little boxes. Soho, Noho, Tribeca, Nolita. But these aren't official government designations. They're mostly inventions of real estate developers and artists.

Tribeca stands for "Triangle Below Canal Street."

Soho is "South of Houston."

But where does the Lower East Side end and the East Village begin? Ask five New Yorkers and you’ll get six different answers. Historically, 14th Street was the line. Nowadays, some people say it’s Houston. The Manhattan map New York is constantly being redrawn by culture and rent prices.

Even the "West Side" isn't just one thing. You have Chelsea, with its high-end galleries and the High Line (which is a map-reading challenge in itself since it's elevated), and then you have Hell's Kitchen. Further north, the Upper West Side feels entirely different—wider sidewalks, more trees, and the massive weight of the American Museum of Natural History anchoring the 70s and 80s.

✨ Don't miss: Finding the Best Zoo in Glendale AZ: Why It Isn't Exactly What You Expect

The "Forgotten" North: Above 110th Street

A lot of maps for visitors sort of... stop... at the top of Central Park. That’s a mistake. Harlem, Washington Heights, and Inwood are where the geography gets really interesting.

The island gets skinny up there.

In Washington Heights, the elevation jumps. You’re not on a flat grid anymore. You’re on cliffs. Bennett Park is the highest natural point in Manhattan, sitting at 265 feet above sea level. If you're looking at a Manhattan map New York and wondering why a certain street doesn't go through, it's probably because there's a literal cliff in the way. You have to use "Step Streets"—literal staircases that serve as public thoroughfares.

Inwood, the very tip of the island, feels like a different planet. It has the only prehistoric forest left in Manhattan. You can walk through Inwood Hill Park and forget you’re in the most densely populated borough in America. The map shows green, but it doesn't show the caves where the Lenape people lived. It doesn't show the salt marshes.

Transit: The Map Under the Map

You can't talk about the surface without talking about the subway. The MTA map is a work of art, but it’s famously geographically inaccurate. It distorts the size of the blocks to make the lines fit.

For example, on the subway map, the walk between the 49th St (N/R/W) station and the 47-50th Sts-Rockefeller Ctr (B/D/F/M) station looks long. In reality? It’s about three minutes. People waste swipes and time transferring underground when they could have just walked above ground.

💡 You might also like: Talofa Airways Headquarters NYT: Why This Small Airline Is a Huge Puzzle

Also, look out for the "L" shape of the 1/2/3 lines vs. the 4/5/6. They hug the sides of the island. If you’re on the Upper East Side and you need to get to the Upper West Side, the Manhattan map New York shows you Central Park is in the way. You can't just take a train across it easily. You’re taking a bus or walking the "transverse" roads. Those transverses—65th, 79th, 86th, and 97th—are sunken below the park's grade so they don't ruin the view for people looking at sheep or trees.

Water, Piers, and the Changing Coastline

Manhattan is growing. Not just up, but out.

If you compare a Manhattan map New York from 1750 to one from 2026, the island is significantly wider. Battery Park City? That’s all landfill. It was built using the dirt and rock excavated during the construction of the original World Trade Center.

The piers used to be the lifeblood of the city, packed with ships from all over the world. Now, they're parks. Pier 57 has a rooftop park. Pier 26 has a tide deck. Navigation today isn't about finding a boat; it's about finding the best spot for a sunset view of the Hudson.

But remember: the water is the boundary. You can't get lost forever. If you walk far enough in any direction (except North), you'll eventually hit a river. The Hudson is on the west, the East River is on the east (even though it's technically a tidal strait and not a river), and the Harlem River separates you from the Bronx in the north.

Actionable Tips for Mastering the Manhattan Map

Don't just stare at the blue dot. Use these mental shortcuts to navigate like a local:

- The Fifth Avenue Divide: Fifth Avenue splits the island into "East" and "West." Address numbers get higher as you move further away from Fifth. If you're at 10 West 18th St, you're right next to Fifth Avenue. If you're at 500 West 18th St, you're basically in the river.

- The "L" Rule for Avenues: In Midtown, most avenues are one-way. A simple trick is that "Left" and "Lower" (as in lower-numbered avenues) often correlate with traffic flow direction, but honestly, just look at the parked cars. They always point the way the traffic goes.

- The "20-Block" Mile: Roughly 20 north-south blocks (streets) equal one mile. Use this to gauge if you should walk or take a cab. Walking 10 blocks? That's half a mile. Easy. Walking 40 blocks? Put on your sneakers or head for the subway.

- Cross-Street Logic: When you're giving an address to a taxi driver or a friend, never just give the number. "I'm at 1200 Broadway" means nothing to a local. They'll ask, "What's the cross street?" Knowing you're at Broadway and 29th is much more helpful than the building number.

- Subway Entrances: Look at the globes outside the stairs. Green globes mean the entrance is open 24/7. Red globes mean it’s either exit-only or has limited hours. Checking this on your Manhattan map New York before you walk three blocks out of your way is a lifesaver.

What Most People Get Wrong

People assume the "Village" is just one place. It’s not. You have the West Village, Greenwich Village, and the East Village. They have completely different vibes and completely different layouts.

The West Village is the most beautiful part of the city, but it's a navigational trap. Streets like Christopher and Bleecker curve and wind. You can walk in a circle for twenty minutes without realizing it because the sun is blocked by the beautiful brownstones.

Another misconception is that Central Park is the "middle" of the island. It’s not. It’s actually shifted slightly to the east. If you’re on the far West Side (near 11th Ave), you have a much longer walk to the park than someone on 1st Ave.

Manhattan isn't just a piece of paper or a digital file. It’s a living, breathing three-dimensional object. There are tunnels running under you, helicopters flying over you, and millions of people moving in a synchronized (yet chaotic) dance. The map is just a suggestion. The best way to learn it? Turn off the phone, start at 59th Street, and just walk south until the street names start sounding like people instead of numbers. That’s where the real city lives.

To truly master the city's layout, your next move should be downloading an offline version of the transit map. Data service in the deep subway stations is notoriously spotty, and having a high-resolution PDF of the actual track layout—not just the simplified Google version—will save you when the "L" train isn't running or the "1" is skipping your stop. Grab a physical map from a subway booth if you can find a staffed one; they are becoming collector's items and offer a perspective that a 6-inch screen simply can't match.