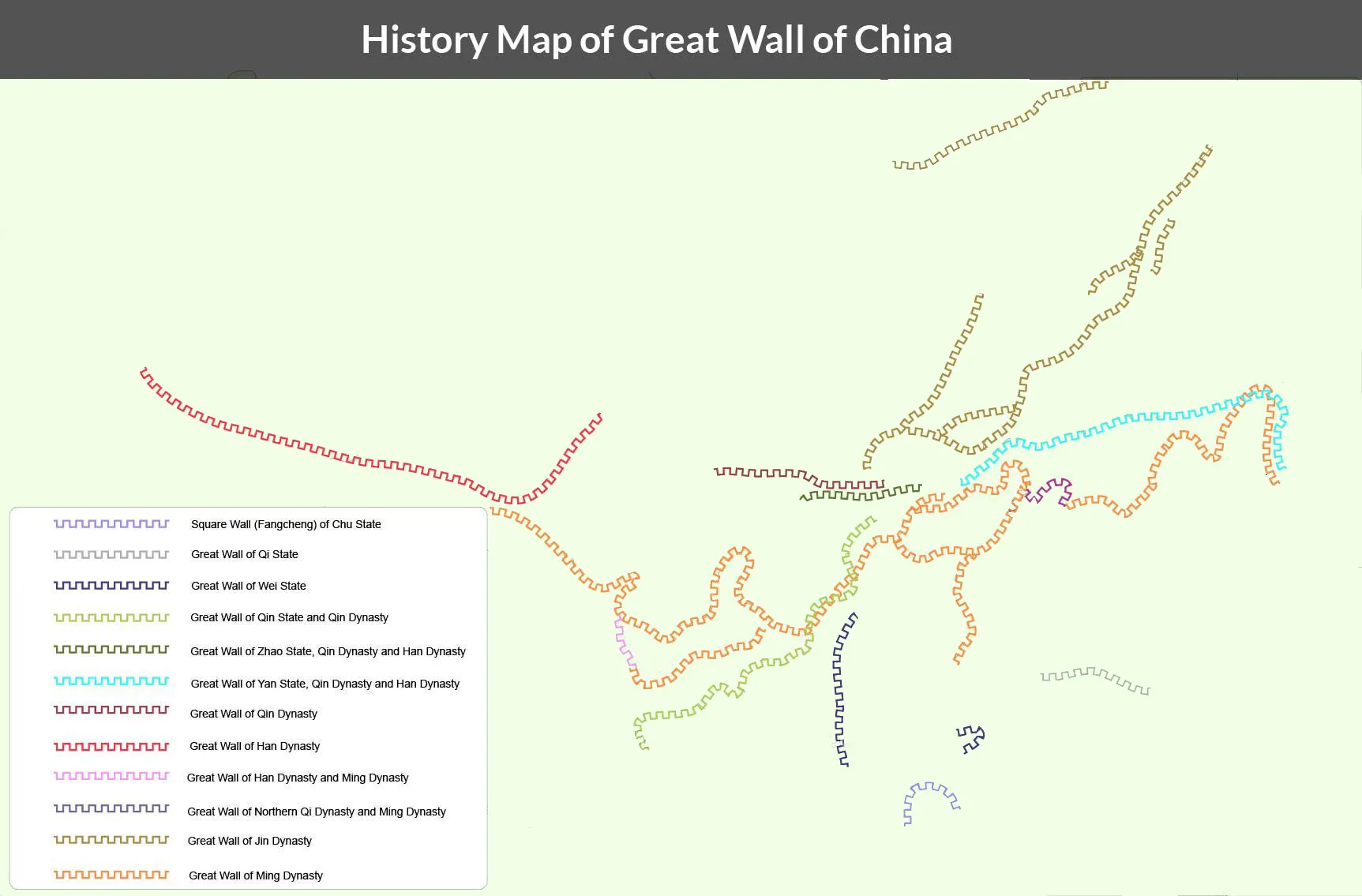

You’ve seen the photos. Those misty, jagged stone spines snaking over emerald ridges at Badaling or Mutianyu. But when you actually sit down and look at a map of China with the Great Wall, things get messy. Fast. Honestly, most people think it’s just one long, continuous line, like a giant scar across the top of the country. It isn't. Not even close.

If you’re trying to visualize where this thing actually sits on a modern map, you have to throw out the idea of a single wall. It’s more of a massive, overlapping network of earthen mounds, brick towers, and natural barriers like cliffs that span thousands of miles.

Where Exactly Does it Sit on the Map?

Basically, the Great Wall isn't just one "thing." It’s a collection of fortifications built over two millennia. If you look at a map of China with the Great Wall today, you’re usually seeing the Ming Dynasty version. That's the one people recognize—the gray stone, the battlements, the stuff that looks like a movie set. This section starts way out east at Shanhaiguan, where the wall literally touches the Bohai Sea (the "Old Dragon’s Head"), and ends way out west at Jiayuguan in the Gobi Desert.

But wait. There’s more.

If you look at maps of earlier dynasties, like the Han or the Qin, the lines crawl even further north and west into what is now Mongolia and Gansu province. Archaeologists have used infrared rangefinders and GPS devices to track down segments that are now just piles of dirt. According to a massive survey by the State Administration of Cultural Heritage (SACH), the total length of all these segments combined is roughly 21,196 kilometers (about 13,171 miles). To put that in perspective, that’s more than half the circumference of the Earth. It’s staggering.

The Geographic "Why" Behind the Lines

Why is it there? It’s not just a random line. The map of China with the Great Wall is essentially a map of ecological boundaries.

For centuries, the wall served as the dividing line between two completely different ways of life. To the south, you had the fertile loess plateau and the Yellow River valley—perfect for sedentary farming and rice or wheat cultivation. To the north? The vast, windswept steppes. This was the land of the nomads. The wall was built where the rainfall started to drop off, making farming impossible and herding the only way to survive. It was a physical manifestation of a "stop" sign for two colliding civilizations.

Navigating the Map: Key Sections You’ll Actually See

When you're staring at a map trying to plan a trip or just understand the geography, you’ll notice most of the "famous" spots cluster around Beijing. This makes sense. Beijing was the capital, the heart of the empire, and it needed the most protection.

- Badaling and Mutianyu: These are the "easy" spots. On a map, they are just north of the city. They’re heavily restored. If you want to see what the Ming emperors wanted the wall to look like, this is it.

- Jiankou: This is the one for the hikers. It’s wild. It’s "original." On a map, it’s a jagged zigzag that looks like a lightning bolt. It’s dangerous because the stone is crumbling, and the inclines are nearly vertical.

- Shanhaiguan: This is the eastern "anchor." It’s where the wall meets the ocean. Historically, this was the "First Pass Under Heaven."

- Jiayuguan: The western end. This is where the Silk Road travelers would say goodbye to "civilization" and head out into the unknown of the desert.

The Map Isn't Just Stone and Brick

One thing people get wrong—kinda constantly—is thinking the wall is only made of rock. If you look at a map of China with the Great Wall in the far west, like in Gansu province, the wall is made of "rammed earth." They literally took desert soil, mixed it with gravel and reeds, and pounded it until it was hard as a rock.

Today, those sections look like melting sand dunes. They don’t look like the "Wall" we see on postcards. But on a map, they are just as vital. They protected the trade routes that brought silk and spices to Europe. Without these dusty, crumbling mounds, the history of global trade would look completely different.

Myths That Mess Up Your Perception

We have to talk about the "Visible from Space" thing. It’s a lie. A total myth. NASA has confirmed it multiple times. From low Earth orbit, the wall is almost impossible to see with the naked eye because it’s the same color as the surrounding terrain. It’s like trying to see a single hair from the top of a skyscraper.

Another misconception? That it was one big wall built all at once. Nope. It was a centuries-long project of "oh no, they’re coming again" additions and repairs. When you look at the map of China with the Great Wall, you’re looking at a timeline of Chinese anxiety and military engineering.

Why the Map Still Matters Today

In 2026, the wall isn't just a pile of rocks; it's a massive conservation project. Climate change is actually hurting it. In the west, desertification and sandstorms are sandblasting the rammed earth sections into nothingness. In the east, heavy rains are causing "wild" sections of the wall to collapse.

🔗 Read more: Finding Your Way: What a Map of Lakewood Ohio Reveals About the City's Grid

Researchers are now using drones and AI-driven 3D mapping to create a digital "twin" of the wall. This lets them see which parts are at risk of falling over before it actually happens. So, the modern map of China with the Great Wall is actually a digital, living document that changes every time a storm rolls through.

How to Use This Information

If you are actually planning to visit or just want to understand the geography better, don't just look at a map of "The Great Wall." Look at a topographical map. See how the wall follows the highest ridges of the mountains. It’s a feat of logistics that seems impossible when you realize they didn’t have cranes or trucks. They used goats, pulleys, and thousands of laborers who often didn't make it home.

To get the most out of your research, follow these steps:

1. Distinguish between the "Wild" and "Restored" walls. If you're using a digital map, the restored areas like Badaling will have roads and bus stops nearby. The "wild" sections like Chengzhiyu or Jiankou will look like nothing but forest on a satellite view until you zoom in deep.

2. Follow the "Nine Garrisons." The Ming Dynasty divided the wall into nine military districts. Each had its own headquarters. If you look up these garrison towns on a map, you’ll find some of the most interesting, non-touristy parts of the wall.

3. Check the weather cycles. If you're looking at the map for travel, remember that the "Great Wall" spans multiple climate zones. It might be a pleasant 20°C in Beijing while a sandstorm is burying the western sections in Gansu.

4. Use Satellite Layers. Standard map views often miss the smaller, earthen segments. Use satellite imagery to find the shadows cast by the old watchtowers. It’s like a giant game of connect-the-dots across the Chinese landscape.

The Great Wall is a ghost. It’s a memory of an empire’s borders carved into the earth. Whether you’re looking at it on a screen or standing on its cold, uneven stones, remember that the map is just a snapshot of a structure that is constantly being reclaimed by the mountains it tried to conquer.