You’ve probably seen the old Westerns where a dusty stockade stands alone against a desert wind, a few soldiers huddling behind wooden walls while waitin' for a wagon train. Honestly, that’s not really Fort Laramie. Not even close. If you head out to eastern Wyoming today, what you’ll find at the confluence of the Laramie and North Platte rivers is something much more sprawling, complex, and—frankly—a bit more tragic than the Hollywood version. Fort Laramie in Wyoming wasn't just a fort; it was the Grand Central Station of the 19th-century American West.

It started as a private business venture. Back in 1834, William Sublette and Robert Campbell built a small log structure they called Fort William to tap into the lucrative buffalo robe trade. They weren't looking to fight a war. They wanted to get rich off furs. But the location was too perfect to stay small. It sat right at the gateway to the Rocky Mountains, a natural bottleneck for anyone heading toward the Pacific.

From Fur Trade to Military Might

The shift from a beaver-pelt warehouse to a military behemoth happened fast. By the late 1840s, the "Great Migration" was in full swing. Thousands of emigrants were trundling past on the Oregon, California, and Mormon Trails. The government realized they needed a presence there to "protect" the trails, though who was protecting whom is still a subject of a lot of historical debate. In 1849, the U.S. Army bought the site for $4,000.

They didn't build a walled fortress.

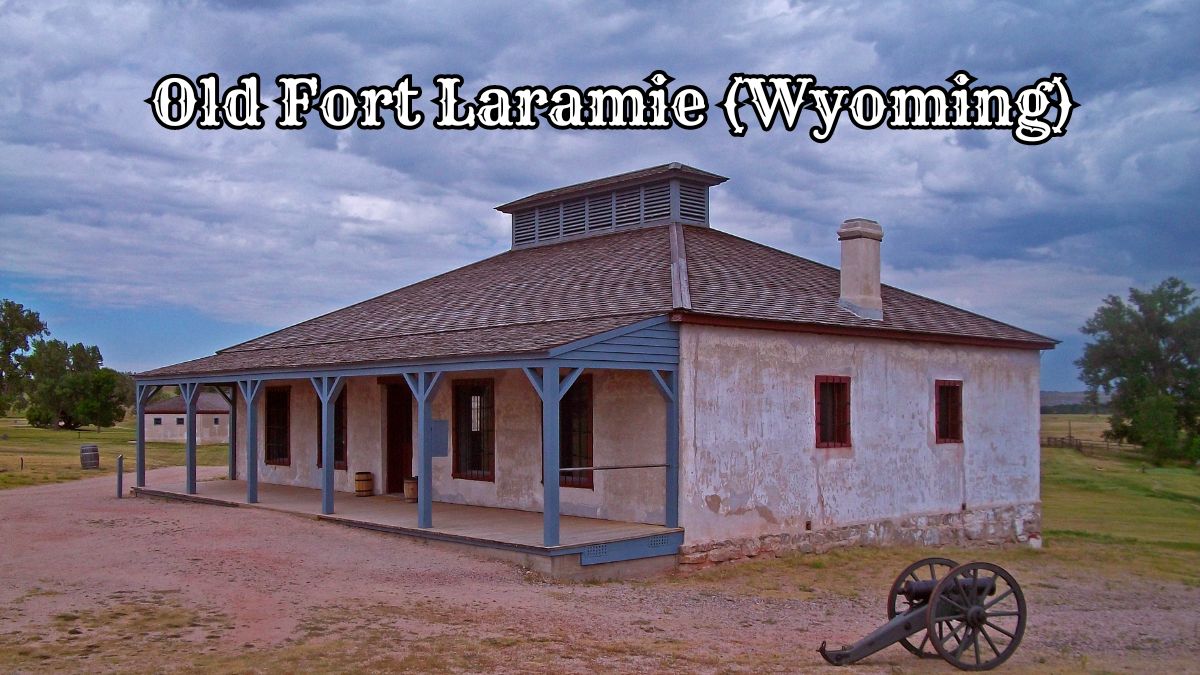

That’s the first thing that trips people up when they visit. Fort Laramie was an "open" fort. There were no massive stone walls or sharpened log pickets surrounding the barracks. Instead, it was a wide-open campus of buildings centered around a parade ground. It looked more like a small, disciplined town than a castle. At its peak, it was a bustling hub where you’d hear a dozen different languages and see everything from U.S. Cavalry officers in crisp blues to Lakota leaders in intricate beadwork and weary pioneers trying to trade their exhausted oxen for anything that could still walk.

The Treaty That Changed Everything (and Then Broke)

You can't talk about Fort Laramie without talking about the Horse Creek Treaty of 1851. This was a massive deal. It was arguably the largest gathering of Native American tribes in history. We're talking about 10,000 to 12,000 people from the Lakota, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Crow, and other nations gathering to negotiate with the federal government.

The goal?

Peaceful passage for settlers and defined tribal territories. The government promised annuities—basically annual payments of goods and food—in exchange for the right to build roads and forts. It was a fragile hope. It lasted about three years before the "Grattan Massacre" happened just down the road over a dispute involving a single cow. One wandering cow led to a misunderstanding, which led to 30 soldiers and a high-ranking lieutenant getting killed, which effectively kicked off decades of intermittent warfare across the plains.

💡 You might also like: Cold Spring to NYC: How to Actually Nail This Trip Without the Crowds

Then came the 1868 Treaty. This one is still legally cited in Supreme Court cases today. It established the Great Sioux Reservation and closed off the Bozeman Trail. It was a rare moment where the tribes actually negotiated from a position of incredible strength after Red Cloud's War. But, like many agreements of the era, the discovery of gold in the Black Hills a few years later made the treaty’s promises inconvenient for the U.S. government. They broke it. That’s the heavy atmosphere you feel when you walk through the ruins today—the weight of broken ink.

What You’ll Actually See at the National Historic Site

When you pull into the parking lot today, managed by the National Park Service, it’s quiet. Maybe too quiet given how loud it used to be. The "Old Bedlam" building is the star of the show. Built in 1849, it’s the oldest documented house in Wyoming. It served as officer quarters and the social heart of the fort. If those walls could talk, they’d tell you about the 1866 "Portugee" Phillips ride, where a man rode 236 miles through a blizzard to get help after the Fetterman Fight. He arrived at Old Bedlam during a Christmas night ball, half-frozen and collapsing, to deliver the news.

The ruins are just as evocative as the restored buildings. The hospital sits on a hill, its crumbling lime-concrete walls looking like something out of a Roman archaeological site.

- The Surgeon's Quarters: Restored and filled with terrifying 19th-century medical tools.

- The Cavalry Barracks: You can see where hundreds of men slept, ate, and waited for orders that often sent them into the harshest conditions imaginable.

- The Bakery: They produced thousands of loaves of sourdough bread daily. You can still smell the phantom yeast (okay, maybe that’s just the Wyoming sagebrush, but you get the idea).

- The Iron Bridge: Built in 1875, it’s one of the oldest spans of its kind west of the Mississippi. It literally bridged the gap between the "civilized" east and the "wild" west.

The Logistics of Frontier Survival

Living at Fort Laramie in Wyoming wasn't exactly a picnic. While officers had it okay, the enlisted men dealt with crushing boredom punctuated by moments of extreme stress. Diet was a major issue. For a long time, it was salt pork, hardtack, and beans. Scurvy was a real threat until they started planting gardens.

👉 See also: Newcastle UK Weather: What Most People Get Wrong

Water was another thing.

They got it from the river, which wasn't always the cleanest source. Typhoid and cholera were constant shadows. Yet, people fought to be stationed here. Why? Because compared to a lonely outpost in the middle of nowhere, Fort Laramie was "civilization." It had a post trader’s store where you could buy luxuries like canned oysters or fine silk if you had the coin. It was the last place to get a decent wagon wheel or a fresh horseshoe before hitting the mountain passes.

Misconceptions and Nuances

A lot of people think the fort was abandoned because it was destroyed in a battle. Nope. It just became obsolete. By 1890, the frontier was "closed" according to the census. The railroad had bypassed the fort years earlier, making the old wagon trails irrelevant. The Army packed up, auctioned off the buildings to local ranchers, and walked away.

For about forty years, Fort Laramie was basically a farm.

People lived in the old officer quarters. They kept hay in the barracks. It wasn't until 1938 that it became a National Monument (later a National Historic Site). We almost lost it to decay and the elements.

✨ Don't miss: Why Everyone Obsesses Over the Pink Palace at Ocean Lakes Family Campground

There's also this idea that it was purely a place of conflict. While the wars were real and devastating, the fort spent more of its life as a place of commerce. It was a melting pot. You had Black Buffalo Soldiers stationed here in the later years. You had Mexican muleteers. You had European immigrants who barely spoke English. It was a messy, loud, vibrant microcosm of what America was becoming—for better or worse.

Planning Your Visit: Real Advice

If you're going, don't just rush through. Give it at least three hours.

- Timing: Go in the late spring or early fall. Summer in Goshen County is brutal—dry, baking heat that makes you realize why the soldiers were always cranky.

- The Walk: Take the path down to the confluence of the rivers. It’s where the fur traders first set up camp. You can feel the breeze coming off the water and understand why this specific spot was chosen. It’s the coolest place on the property, literally.

- The Junior Ranger Program: Even if you don't have kids, ask to see the materials. The Park Service has done a great job of incorporating the tribal perspectives lately, which gives a much more honest view of the "protection" the fort offered.

- Photography: The light at "golden hour" hitting the lime-concrete ruins of the hospital is a photographer's dream. The textures of the crumbling walls against the Wyoming sky are incredible.

Actionable Insights for the History Traveler

To get the most out of Fort Laramie in Wyoming, you need to look beyond the plaques.

- Check the Calendar: The Park Service often runs "Living History" weekends where volunteers dress in period-accurate wool uniforms. It’s hot, itchy, and provides a visceral sense of the discomfort of 1870s military life.

- Read the Primary Sources: Before you go, look up the diary of Margaret Carrington or the letters of soldiers stationed there. It changes how you see the empty rooms when you know exactly who was crying or cheering inside them.

- Respect the Silence: When you stand on the parade ground, turn off your phone. Listen. You can almost hear the jingle of harness brass and the call of the bugle.

- Combine the Trip: Don’t just do the fort. Drive twenty minutes to Guernsey to see the Oregon Trail Ruts. These are deep grooves carved into solid sandstone by thousands of wagon wheels. Seeing the ruts first makes the scale of Fort Laramie make much more sense.

Fort Laramie isn't a theme park. It's a somber, beautiful, and deeply important piece of the American puzzle. It represents the ambition of a growing nation and the displacement of the people who were already there. It’s a place of iron, wind, and memory that demands you sit still for a moment and just think.

Next Steps for Your Trip

- Download the NPS App: It has an offline tour map because cell service out there is spotty at best.

- Pack Water: There is very little shade between the buildings.

- Research the 1868 Treaty: Understanding the legal language of that document will make your visit to the "Treaty Room" significantly more impactful.

- Check Road Conditions: If you're visiting in the shoulder seasons, Wyoming weather can flip from 60 degrees to a blizzard in two hours. Check the WYDOT sensors before heading out from Cheyenne or Casper.