Forget the glitter. Honestly, if you grew up thinking fairies were just tiny women in tutus with magic wands, Brian Froud’s work was probably a massive shock to your system. Most people look at the phrase good faeries bad faeries and expect a simple binary—angels versus demons, light versus dark. But that’s not how the Froudian universe works. It’s not how folklore works either.

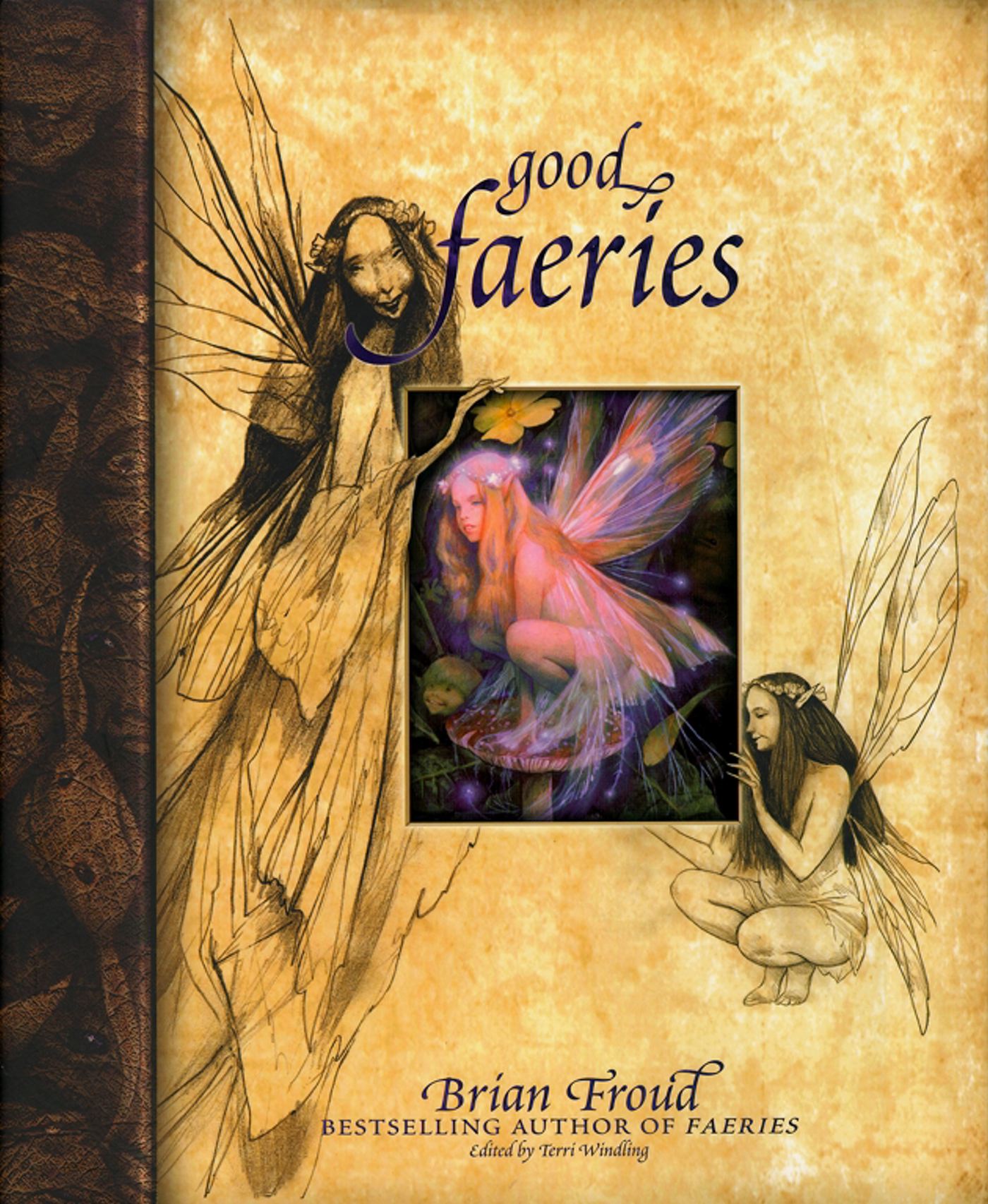

Brian Froud, along with Alan Lee, basically redefined the visual language of the "Otherworld" back in the late 70s and early 80s. When Good Faeries/Bad Faeries was published, it didn't just give us pretty pictures. It gave us a taxonomy of the weird. It showed us that a "good" faery might still pinch you until you're blue, and a "bad" one might just be misunderstood—or, you know, actually trying to eat your soul.

There is a gritty, organic reality to these creatures. They look like they were pulled out of a peat bog or squeezed from the bark of an ancient oak. They have warts. They have crooked teeth. They have personalities that are, frankly, exhausting.

The Problem with Calling Them Good

What does "good" even mean in a world where morality is based on ancient taboos rather than modern ethics? In the world of good faeries bad faeries, a good faery is often just one that hasn't decided to ruin your life today.

Froud captures the Seelie Court—the "blessed" ones—with a certain ethereal grace, but there’s always an edge. Think of the Butterscots or the various flower spirits. They are beautiful, sure, but they are also fickle. They are flighty. If you forget to leave out a bowl of milk, that "good" faery might decide to tangle your horse's mane or sour your cream just for the laughs.

Katherine Briggs, the legendary folklorist who Froud often drew inspiration from, noted that the Fair Folk operate on a system of reciprocity. It’s a contract. You follow the rules, they leave you alone (or occasionally help). You break the rules, and things go south fast. Froud’s illustrations reflect this perfectly. Even the most radiant beings in his book have eyes that suggest they know exactly how you’re going to die. It’s a bit unsettling.

When Bad Faeries Are Actually Just Dangerous

Then you have the Unseelie Court. These are the "bad" ones. But again, it’s not always about evil in a cinematic sense. It’s about nature. Is a hurricane evil? No, but it’ll kill you.

The "Bad Faeries" section of the book is a masterclass in character design. You’ve got creatures like the Gloomin, who just sort of exude a sense of damp, gray misery. Then there’s the Oolert, or the various screeching things that hide under floorboards. These aren’t villains with monologues. They are pests. They are manifestations of our own anxieties, fears, and the physical decay of the world around us.

Take the "Gutter-Gringer," for example. It’s a creature of filth and sharp edges. It doesn't want to conquer the world; it just wants to make sure you trip and hurt yourself. This is the brilliance of the good faeries bad faeries dichotomy—it captures the sheer pettiness of the supernatural. Sometimes the universe isn't out to get you; it's just playing a mean prank.

✨ Don't miss: Who was in Magic Mike: Why that original 2012 cast still hits different

The Influence of Labyrinth and The Dark Crystal

It’s impossible to talk about Froud’s faeries without mentioning Jim Henson. Froud was the conceptual designer for The Dark Crystal (1982) and Labyrinth (1986). If you look at the Skeksis or the goblins in Jareth’s castle, you are looking at the "Bad Faeries" come to life.

They are tactile. They have physical weight.

- The Skeksis represent the ultimate "Bad Faery" archetype: greed, decay, and the fear of death.

- The Mystics are the "Good," but they are slow, fading, and almost useless in their passivity.

- Hoggle from Labyrinth is the quintessential middle-ground creature—cowardly, grumpy, but ultimately capable of heart.

This isn't Disney. It's much older. It feels like something found in a dusty attic in Devon, England, where Froud actually lives and works.

Why We Still Care Decades Later

We live in a very sterile world. Everything is plastic, digital, and hyper-explained. Good faeries bad faeries offers an escape back to a world that is messy and unexplained.

People are obsessed with "Cottagecore" and "Goblincore" now. You see it all over TikTok and Pinterest. But Froud was doing Goblincore before it had a name. He understood that there is beauty in the gnarled and the grotesque.

There’s a specific psychological weight to his work. When you look at a Froud faery, you aren't looking at a cartoon. You’re looking at an archetype. Carl Jung would have had a field day with this stuff. The "Bad" faeries represent our shadow selves—the parts of us that are greedy, lazy, or cruel. The "Good" ones represent our aspirations, but also our fragility.

The Hidden Rules of the Otherworld

If you actually want to survive an encounter with these things (hypothetically, obviously), you have to understand the rules Froud emphasizes through his art and notes.

- Iron is your best friend. Cold iron wards off the nastier bits of the Unseelie Court.

- Names have power. Never give a faery your real name. Use a nickname. "Steve" is fine. "The Great Architect of My Own Destiny" is asking for trouble.

- Don't eat the food. This is Folklore 101. You eat a blackberry in the Otherworld, and you’re stuck there forever. Or you come back and 100 years have passed.

- Gratitude is a trap. Never say "thank you" to a faery. It implies you owe them something. Instead, say "I am favored" or "This is well-received." It sounds pretentious, but it keeps you from becoming a slave to a goblin.

The Technical Artistry Behind the Magic

Froud doesn't just draw; he layers. He uses acrylics, colored pencils, and pastels to create textures that look like they’re vibrating. The way he uses light is particularly interesting. In the "Good" section, the light is often internal—the creatures seem to glow from within. In the "Bad" section, the light is harsh, external, or non-existent, creating deep shadows where things can hide.

He often talks about "seeing" the faeries in the land around his home. He isn't being literal—or maybe he is—but he’s describing a process of pareidolia. That’s when you see faces in clouds or knots in wood. His art teaches us to look at the world that way. Once you’ve spent enough time with good faeries bad faeries, you can’t help but see a little face in your morning toast or a pair of eyes in the dark corner of your garage.

It's a way of re-enchanting the world.

🔗 Read more: Why This Is Us Season 3 Was The Show's Messiest, Most Rewarding Pivot

Moving Beyond the Book

If you've already devoured the book, there are plenty of places to go next. You have to look at Faeries, the original 1978 book he did with Alan Lee. It’s more academic, more sprawling. Then there's The Pressed Fairy Journal of Lady Cottington, which is a hilarious, darker take on the "Victorian fairy" craze. It’s essentially a book about a woman who squashes fairies in her diary like dried flowers. It’s morbid, funny, and very Froud.

There’s also the work of his wife, Wendy Froud, who is a master puppet maker. She’s the one who actually built Yoda for The Empire Strikes Back. Their son, Toby Froud (yes, the baby in the striped leggings from Labyrinth), is now a creature designer himself, working on things like The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance.

The legacy is a literal family business of making monsters.

How to Apply Froudian Wisdom to Your Life

You don't have to believe in little green men to get something out of good faeries bad faeries. It’s about a mindset.

First, stop looking for "perfect." The most beautiful things in Froud's world are asymmetrical. They are scarred. They are weird. Apply that to your own life. Your "flaws" are usually what make you an interesting character rather than a background extra.

Second, respect the unknown. We think we have the world mapped out because we have GPS and Wikipedia. But there’s a lot of "weird" left in the world—strange coincidences, gut feelings, and the way the woods feel at 3:00 AM. Froud’s work encourages us to sit with that discomfort rather than trying to explain it away.

✨ Don't miss: Sung Jin Woo Shadow Army: What Most People Get Wrong

Finally, keep your sense of humor. The "Bad" faeries are often just ridiculous. They are manifestations of our own silliness. If you can laugh at the Gutter-Gringer, it loses its power over you.

Actionable Steps for the Aspiring Mythologist

- Start a Sketchbook: You don't need to be an artist. Go outside, find a weird-looking rock or a knotted tree root, and try to see the "face" in it. Draw what you see, not what you think a fairy should look like.

- Read the Primary Sources: Check out The Secret Common-Wealth by Robert Kirk. He was a 17th-century Scottish minister who claimed to have visited the Fair Folk. It’s the "real" version of what Froud illustrates.

- Audit Your Space: Froudian philosophy suggests that clutter attracts certain types of "Bad" faeries. If you're feeling stuck or "gloomy," clean your physical space. It’s a mundane way to perform a banishing ritual.

- Support Physical Media: In an age of AI-generated art, Froud’s tactile, hand-drawn work is more important than ever. Buy the actual physical book. The texture of the paper and the smell of the ink are part of the experience that a screen just can't replicate.

The world of good faeries bad faeries isn't just a book on a shelf. It’s a lens. Once you put it on, the world looks a lot more crowded, a lot more dangerous, and a whole lot more interesting. Don't say I didn't warn you when you start seeing goblins in your laundry pile.