Let's be real. Most of us have spent way too much time staring at a height weight table for women on a dusty office door or a PDF on some government website, wondering if we "measure up." It’s kinda stressful. You see a number, you look at the scale, and suddenly your whole mood for the week is decided by a grid created decades ago.

But here’s the thing: those tables are often misunderstood, and honestly, sometimes they're just flat-out misleading if you don't know the context behind the math.

We need to talk about where these numbers actually come from. Most of the standard charts you see today are descendants of the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company tables from the 1940s and 1950s. Think about that for a second. These were developed to help insurance companies predict mortality—basically, how likely you were to die—based on data from a very specific, mostly white, mid-century population. They weren't exactly thinking about modern muscle mass, bone density variations, or the fact that a "medium frame" is incredibly subjective.

📖 Related: How Much Do Nurses Make in the Army? The Real Math on Military Pay

The Problem with the Standard Height Weight Table for Women

The biggest issue is that a basic table is a blunt instrument. It treats every woman of the same height as if they should have the identical physical composition. It doesn't care if you're a marathon runner with legs of steel or someone who hasn't hit the gym in three years.

Muscle is dense. It’s heavy.

If you're 5'6" and weigh 160 pounds, a traditional height weight table for women might flag you as "overweight." But if that weight is largely lean muscle, your metabolic health could be lightyears ahead of someone who weighs 130 pounds but has very little muscle mass—what doctors sometimes call "normal weight obesity."

The BMI (Body Mass Index), which is the foundation for most of these tables, was never even intended to be a diagnostic tool for individuals. Adolphe Quetelet, the Belgian mathematician who created the formula in the 1830s, was trying to define the "average man" for social statistics. He wasn't a doctor. He wasn't looking at health outcomes. He just liked patterns.

Yet, here we are, nearly 200 years later, using his "Quetelet Index" to decide if we should feel good about our bodies.

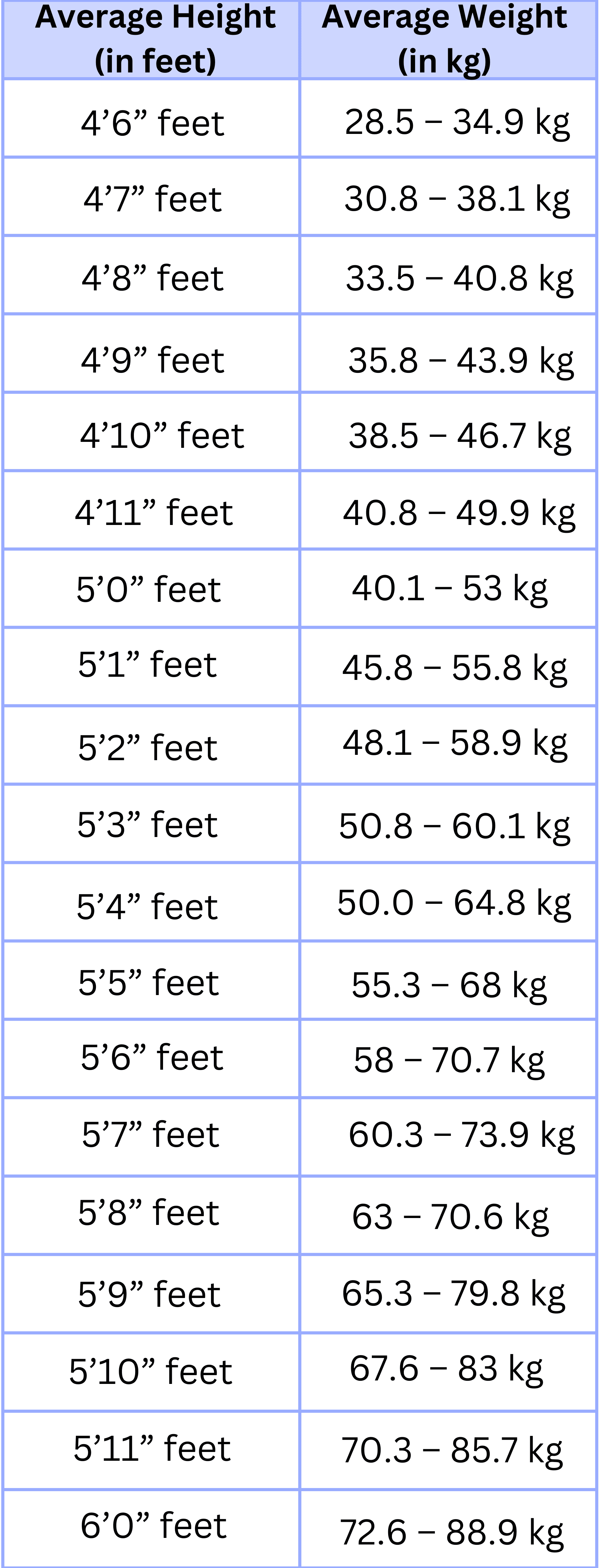

What the Numbers Actually Look Like (Roughly)

Since I promised no perfect tables, let's look at the ranges as a narrative. For a woman standing 5 feet 4 inches, the "healthy" range is typically cited between 108 and 145 pounds. That is a massive 37-pound gap. Why? Because frame size matters.

If you have a small frame (narrow shoulders, thin wrists), you'll likely sit at the lower end. A large frame? You’ll be at the top.

If you're 5'2", the range usually starts around 101 and goes to 135. At 5'8", you're looking at 122 to 164. Notice how the "buffer" grows as you get taller? This accounts for the sheer volume of bone and tissue required to keep a taller human upright. But again, these are just guardrails. They aren't the law.

Why Your "Frame Size" Changes Everything

You've probably heard someone say they're "big-boned." People usually roll their eyes, but there is actual science there. Bone structure varies wildly between different ethnicities and individuals.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) used to suggest a simple wrist measurement to determine frame size. Basically, if you wrap your thumb and middle finger around your wrist and they overlap, you're a small frame. If they just touch, you're medium. If they don't meet, you're large-framed. It’s a bit "back-of-the-napkin" science, but it highlights that your skeleton's weight isn't a constant.

A woman with a larger skeletal structure will naturally weigh more at the same height as someone with a delicate frame, even with the exact same body fat percentage. The height weight table for women doesn't always make that distinction clear, leading a lot of women to chase a number that is physically impossible for their anatomy to reach safely.

The Hidden Danger of the "Ideal" Number

Focusing solely on the table can lead to something called weight cycling, or yo-yo dieting. It's exhausting.

When you're obsessed with hitting a specific number on a grid, you might resort to extreme calorie deficits that eat away at your muscle tissue. This actually slows down your metabolism. So, you hit the "target" weight, but you're physically weaker and your body is now primed to regain fat more quickly because your "engine" (your muscle) has shrunk.

Health is way more than a ratio of gravity's pull on your body.

We have to look at metabolic markers. Things like:

💡 You might also like: Leg Press Legs: Why Your Form Is Killing Your Gains

- Blood pressure (120/80 mmHg is the gold standard).

- Fastng blood glucose levels.

- Cholesterol ratios (HDL vs. LDL).

- Waist-to-hip ratio.

That last one—waist-to-hip ratio—is actually becoming much more popular in clinical settings than the standard height weight table for women. It tells you where you store your fat. Fat stored around the midsection (visceral fat) is much riskier for heart health than fat stored in the hips or thighs.

What the Experts Say (Beyond the Grid)

Dr. Margaret Ashwell, a prominent nutritionist and researcher, has long advocated for the "waist-to-height ratio." Her rule of thumb is simple: keep your waist circumference to less than half your height.

If you are 64 inches tall (5'4"), your waist should ideally be 32 inches or less.

This is often a much more accurate predictor of health than a weight table because it ignores the "heavy muscle" vs. "heavy fat" debate. It focuses purely on central adiposity.

Also, we can't ignore age. As women transition through menopause, hormonal shifts (specifically the drop in estrogen) naturally lead to a redistribution of weight. A "healthy" weight at age 22 might not be the healthiest weight at age 65. Some research actually suggests that carrying a tiny bit of extra weight in older age can provide a "buffer" against bone loss and frailty.

Real Examples of How the Table Fails

Take an elite female athlete. Let’s say a CrossFit competitor who is 5'5" and weighs 170 pounds. According to a standard height weight table for women, she is "Obese Class I."

Is she?

No. She likely has a body fat percentage under 20% and resting heart rate of 50 beats per minute.

On the flip side, consider a woman who is 5'5" and weighs 120 pounds. She fits perfectly in the "ideal" box. However, she smokes, eats mostly processed sugar, and has zero cardiovascular endurance. She might have high internal fat (visceral fat) surrounding her organs.

Who is healthier? The one the table calls "obese" or the one it calls "perfect"?

The answer is obvious, but our healthcare systems are still stuck on the grid. It’s easier to code into a computer than a nuanced conversation about lifestyle and body composition.

How to Actually Use This Information

If you're going to use a height weight table, use it as a starting point for a conversation with your doctor, not a final verdict on your self-worth. It’s a data point. One of many.

💡 You might also like: Carb intake for weight loss: Why your "low carb" plan is probably backfiring

Step 1: Check the Range

Look at the range for your height. If you are significantly outside of it—either way above or way below—it’s worth asking why. Is it lifestyle? Genetics? Medication?

Step 2: Measure Your Waist

Forget the scale for a second. Take a soft measuring tape. Measure right above your belly button. If that number is more than half your height, that’s a signal to look at your metabolic health, regardless of what the weight table says.

Step 3: Assess Your Energy

How do you feel? If you're at your "ideal" weight but you're constantly tired, cold, and losing hair, your body is telling you that the number on the chart is too low for your specific biology.

Step 4: Focus on Function

Instead of chasing a weight, chase a capability. Can you carry your groceries up three flights of stairs? Can you go for a 30-minute walk without being winded? Can you lift a heavy suitcase? Functional strength is a far better indicator of longevity than fitting into a specific row on a 1950s insurance chart.

Moving Beyond the Table

We are finally seeing a shift in how medicine views "healthy" weights. The American Medical Association (AMA) recently adopted a new policy that acknowledges the limitations of BMI, noting its historical bias and its failure to account for differences across race and age groups.

This is huge.

It means the "standard" is finally being questioned by the people who set the standards.

Your body is a complex, biological machine. It isn't a static point on a graph. Factors like hydration, menstrual cycles (which can cause 3-5 pounds of water weight fluctuation in a single week!), and even how much salt you had for dinner last night can mess with the scale.

The next time you see a height weight table for women, remember that it was designed for averages, and you are an individual. Use it for context, but don't let it be the boss of you.

Focus on eating whole foods, moving your body in ways that feel good, and getting enough sleep. If you do those things, your weight will eventually settle into the range that is actually "ideal" for your specific frame and genetics, whether or not it perfectly matches the little box on the paper.

Actionable Takeaways for Your Health Journey

- Get a Body Composition Scan: If you’re curious, skip the scale and get a DEXA scan or use a Bioelectrical Impedance scale. These aren't 100% perfect, but they'll give you a much better idea of your fat-to-muscle ratio than a height weight table.

- Track Non-Scale Victories: Are your clothes fitting better? Is your skin clearer? Is your sleep improving? These are the real metrics of a healthy lifestyle.

- Talk to a Pro: If you're worried about your weight, ask your doctor for a full metabolic panel. Check your A1C, your thyroid (TSH), and your vitamin D levels.

- Prioritize Protein: Maintaining muscle mass as you age is the single best thing you can do for your metabolism, regardless of your height or weight.

- Stop the Comparison: Comparing your 40-year-old body to a chart based on 20-year-olds (or vice versa) is a recipe for misery. Meet your body where it is today.