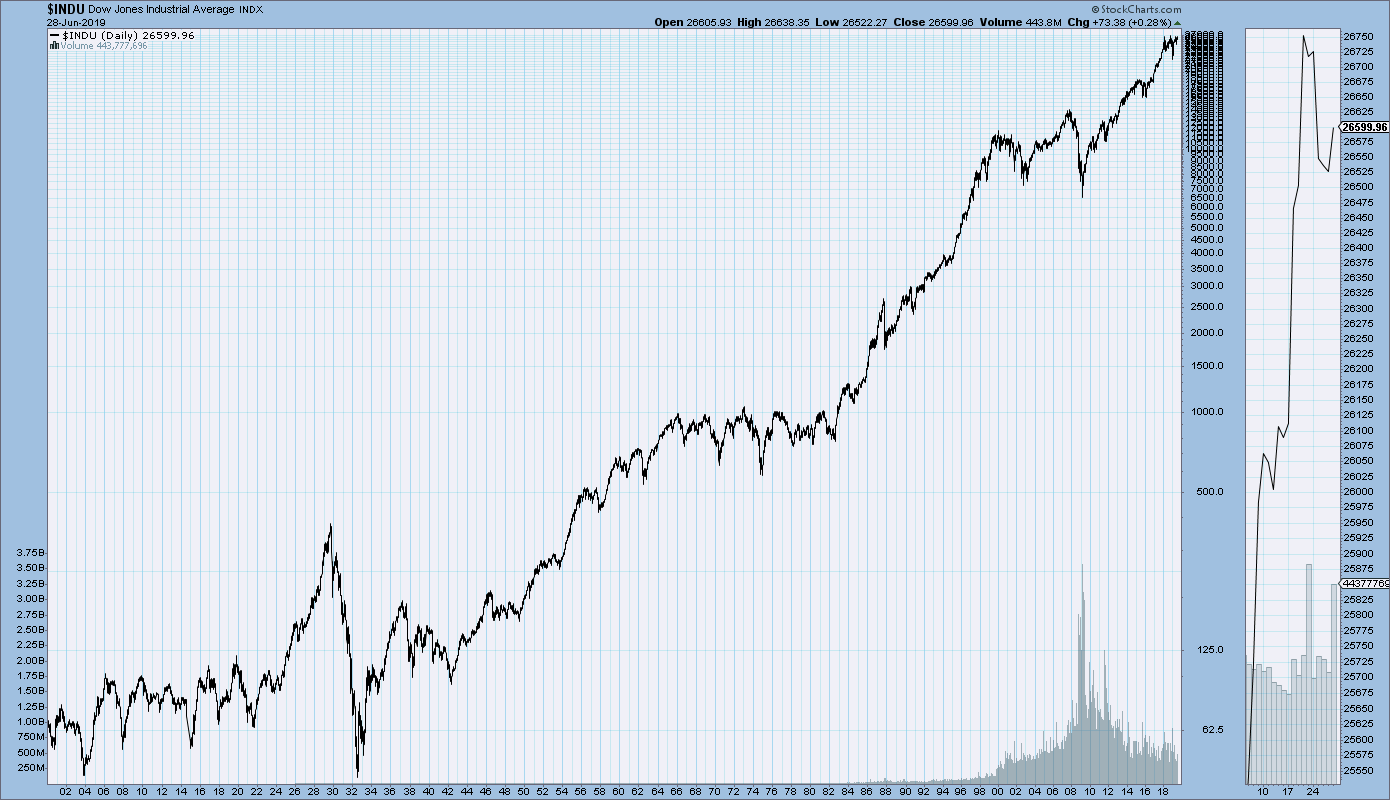

You've probably seen the ticker scrolling across the bottom of the TV screen or flashed on your phone: the Dow is up 200 points, or maybe it’s cratering. Most people treat these numbers like the weather. It’s just something that happens. But if you actually look at historical DJIA closing prices, you start to see they aren't just random digits. They are a diary of every panic, every technological breakthrough, and every massive cultural shift we’ve had since the 1800s.

Honestly, the "Dow 30" is a bit of a weirdo in the finance world. Unlike the S&P 500, which cares about how big a company is (market cap), the Dow just adds up the stock prices of 30 "blue-chip" companies and divides them by a funky number called the Dow Divisor. It's old-school. Some say it's outdated. Yet, when the world wants to know "how the market did today," they still look at where the Dow closed.

The Early Days: When 100 Points Was a Pipe Dream

On May 26, 1896, Charles Dow stood up and said, "Here’s the number." That first close? 40.94.

Back then, the index was mostly smokestacks and railroads. Sugar, tobacco, gas, and rubber. Out of the original twelve companies, only General Electric survived in the index for a century (and even they got the boot eventually in 2018). For decades, the index stayed in the double digits. It took until 1906 just to hit 100.

✨ Don't miss: Pornhub Started in 2007: What Most People Get Wrong About Its History

Think about that. The market spent years grinding through panics and tiny rallies just to reach triple digits.

Then came the Great Depression. This is where historical DJIA closing prices get really dark. In September 1929, the Dow hit a high of 381.17. People thought the party would never end. But by July 1932, it had collapsed to 41.22.

Basically, the market wiped out thirty years of progress in less than three. It didn't get back to its 1929 peak until 1954. That's twenty-five years of waiting just to break even.

The Modern Milestones and the 1,000-Point Barrier

For a long time, the number 1,000 was the ultimate "final boss" for investors. The Dow teased it for years in the 60s but couldn't quite hold it. It finally closed at 1,003.16 on November 14, 1972.

But then, things accelerated.

If you look at the timeline of "first-time" closes, the gaps between the big milestones started shrinking. It's almost like the index discovered caffeine.

- 10,000: March 29, 1999 (10,006.78)

- 20,000: January 25, 2017 (20,068.51)

- 30,000: November 24, 2020 (30,046.24)

- 40,000: May 17, 2024 (40,003.59)

- 49,000: January 6, 2026 (49,462.08)

Just a few days ago, on January 12, 2026, the Dow set its current record-high close at 49,590.20. We are literally knocking on the door of 50,000. It’s wild to think that back in the 70s, people were popping champagne over 1,000.

Why do the jumps seem so much bigger now?

It’s mostly math. Going from 10,000 to 11,000 is a 10% move. Going from 40,000 to 41,000 is only a 2.5% move. The "points" sound scarier or more exciting than they actually are. This is a huge trap for new investors. They see a 500-point drop and panic, but in 2026, a 500-point drop is barely a 1% dip. In 1987, a 500-point drop was a 22% catastrophe known as Black Monday. Context is everything.

💡 You might also like: Why 10 Year Fixed Mortgages Are The Smartest Move (Or The Biggest Mistake) Right Now

The Crashes That Define the Data

You can't talk about historical DJIA closing prices without talking about the days the floor fell out.

Black Monday (October 19, 1887) remains the single worst day in history by percentage. The Dow fell 22.61% in a single session. No warning. Just a total liquidation.

Then you have the 2008 Financial Crisis. The Dow closed at 14,164 in late 2007. By March 2009, it hit a low of 6,547. That was a brutal 54% haircut.

And don't forget the COVID-19 crash in March 2020. The market was hitting highs near 29,000, then suddenly it was plunging 3,000 points in a day. It felt like the world was ending, yet by the end of that same year, the Dow was back at record highs.

What Actually Drives These Numbers?

It’s easy to think it’s just "the economy," but it’s more specific than that. The Dow is price-weighted, meaning Goldman Sachs (with its high share price) has way more influence on the daily close than a company like Apple if Apple's share price is lower due to splits.

Here are the big movers:

- Interest Rates: When the Fed hikes rates, the Dow usually groans.

- Corporate Earnings: If the 30 companies in the index aren't making money, the index can't go up.

- The "Dow Divisor": This is the secret sauce. Every time a company does a stock split or a new company is added, the divisor is adjusted so the index doesn't just "drop" for no reason.

Putting the Data to Use

Looking at historical DJIA closing prices shouldn't just be a history lesson. It’s about perspective.

🔗 Read more: USD to Kenya Shillings Exchange Rate Today: What Most People Get Wrong

Most people get wrong that the Dow is a "representative" sample. It’s not. It’s only 30 companies. But because those 30 are the "royalty" of American business—Visa, Microsoft, Disney, UnitedHealth—they tend to lead the way.

Your Action Plan:

- Stop Obsessing Over Points: Look at percentages instead. A 400-point move today is normal noise.

- Check the Dividends: The closing price you see on the news doesn't include dividends. If you look at the "Total Return" of the Dow, the performance is actually much higher than the raw price suggests.

- Use the 200-Day Moving Average: If the current close is way above its 200-day average, the market might be "overextended." If it’s below, it might be a buying opportunity.

- Mind the "Dogs": Some people use the "Dogs of the Dow" strategy, where they buy the 10 highest-yielding stocks in the index at the start of the year. Historically, it’s a decent way to find value when the rest of the market feels overpriced.

The Dow just hit nearly 50,000. Whether it stays there or pulls back, the history shows one thing clearly: the trend, over a long enough timeline, has always been up. But the rides are never smooth.