In 1903, most people thought the automobile was a toy for the rich that would eventually break and be forgotten. It was loud. It was smelly. It scared horses. But Horatio Nelson Jackson, a Vermont doctor with a taste for adventure and a very thick wallet, didn't buy into the skepticism. While sitting in San Francisco’s University Club, he made a $50 bet—a massive sum at the time—that he could drive a car from California to New York City in less than 90 days.

He had no map. There were no paved highways. GPS wouldn't exist for decades. Horatio's drive America's first road trip was essentially a suicide mission for a machine that barely functioned on flat dirt.

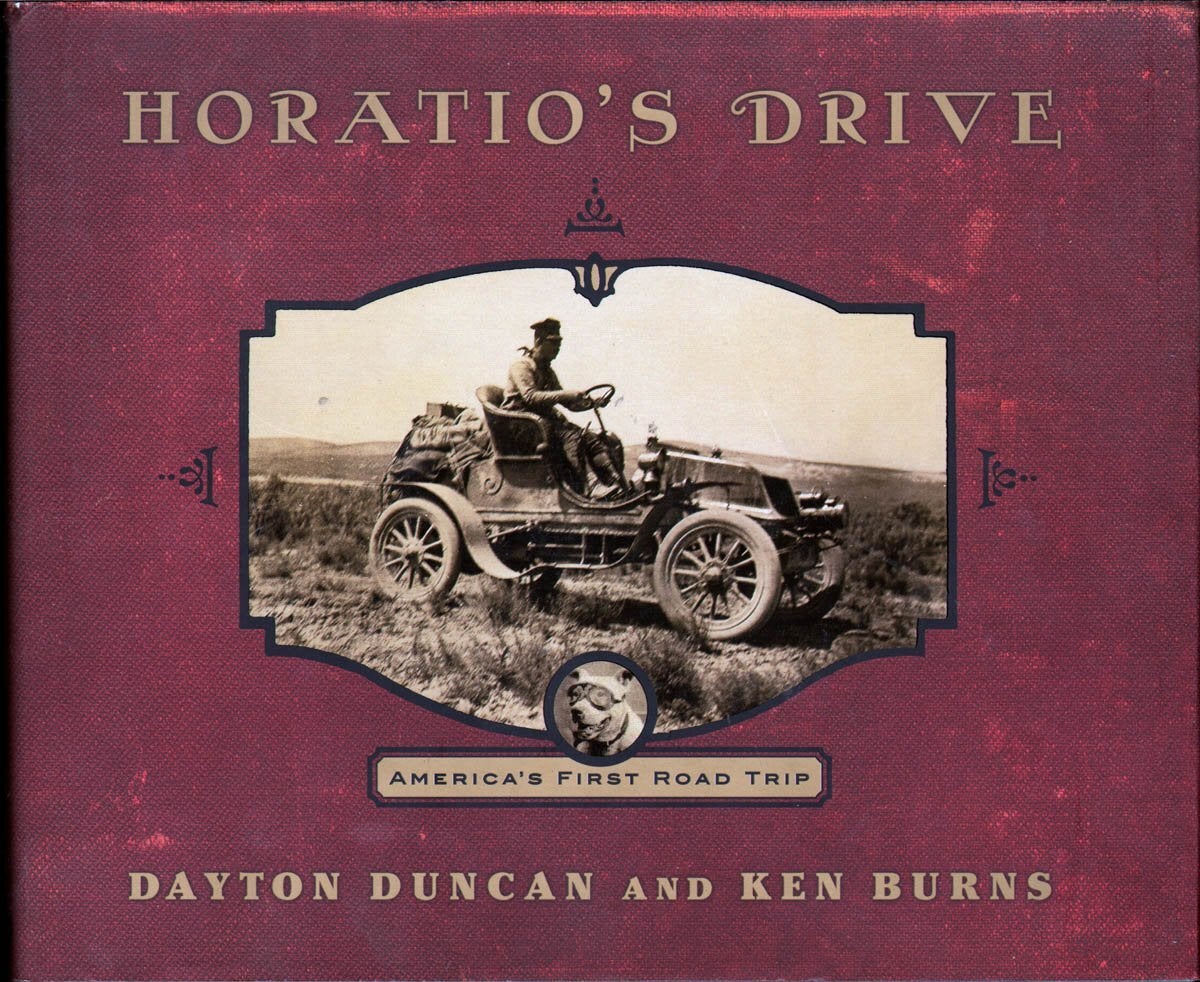

Jackson didn't even own a car when he made the bet. He went out and bought a used 1903 Winton touring car, which he affectionately named "Vermont." He hired a mechanic named Sewall K. Crocker, stuffed the car with extra fuel cans, spare tires, and some camping gear, and headed east. People genuinely thought they were crazy.

The Reality of 1903 Roads (Or Lack Thereof)

You have to understand that "roads" back then were mostly just widened cow paths. If it rained, the path turned into a swamp. If it was dry, the dust was so thick you couldn't breathe. Jackson and Crocker spent more time pulling the Winton out of the mud with a block and tackle than they did actually driving.

👉 See also: Lexington Kentucky Road Conditions: What Most Drivers Get Wrong

They weren't following a highway system. They were following the Oregon Trail and railroad tracks. Sometimes, they’d drive 15 miles in a single day and call it a success. Honestly, the mechanical failures were constant. They blew out tires. They broke axles. They lost their cooking gear when it bounced out of the car on a rocky pass in the Sierras.

Enter Bud: The Goggled Mascot

About halfway through the journey, in Idaho, Jackson bought a Pit Bull Terrier named Bud. This is probably the most famous part of the story, but it wasn't just for companionship. The dust was so brutal on the dog’s eyes that Jackson fitted him with a pair of custom driving goggles. Bud became a national celebrity. People would wait for hours in small towns just to see the dog in the goggles.

Bud reportedly grew to love the car so much that he’d jump in the front seat the second he heard the engine crank. It’s kinda wild to think that the first cross-country road trip included a dog in goggles, but that’s the level of eccentricity we’re dealing with here.

The Rivalry That Pushed the Limits

Jackson wasn't the only one trying to do this. Once word got out that a Winton was crossing the country, other car manufacturers smelled a marketing opportunity. The Packard Company sent out a car called "Old Pacific," and Oldsmobile sent another. It became a race.

🔗 Read more: Moroccan Money to Dollars: What Most People Get Wrong

This changed everything. It wasn't just a gentleman's bet anymore; it was a battle for the future of the American auto industry. If Jackson failed, it would prove that cars were fragile. If he succeeded, it would prove they were the future.

Jackson had a head start, but the Packard team was gaining ground because they had better corporate backing. Jackson was just a guy with a mechanic and a dog. He had to have parts expressed-mailed to train stations ahead of him. He waited days for a single wheel to arrive by rail. The stress must have been insane.

Navigation by Guesswork

Imagine trying to cross Wyoming with no signs. Jackson often relied on directions from locals. In one famous instance, a woman intentionally gave him the wrong directions so her family could see the "horseless carriage" drive by their farm. He drove miles out of his way just to be a localized tourist attraction.

He also ran out of gas. A lot. This was before gas stations existed, so he had to buy fuel from general stores or pharmacies, where it was sold in small quantities for cleaning or lighting.

Why Horatio's Drive Matters Today

Most people think of the American road trip as a 1950s invention with neon signs and diners. But Horatio's drive America's first road trip set the template for the rugged, individualistic way we view travel. It wasn't about the destination. It was about the fact that he arrived at all.

When Jackson finally rolled into New York City on July 26, 1903, he had used 63 days of his 90-day limit. He didn't even collect the $50 bet. He didn't care about the money. He had spent about $8,000 of his own money—equivalent to over $250,000 today—to win a fifty-dollar bet.

- He proved the internal combustion engine could survive the elements.

- He sparked the "Good Roads Movement" that eventually led to the Interstate Highway System.

- He turned the car from a luxury novelty into a tool for freedom.

The Technical Nightmare of the Winton

The Winton itself was a beast to handle. It was a two-cylinder, 20-horsepower machine. To put that in perspective, a modern lawn tractor often has more power. It had a chain drive, similar to a bicycle, which would frequently snap or get clogged with grit.

Jackson and Crocker had to be MacGyver-level resourceful. They used hemp rope to wrap the tires when the rubber wore off. They used water from cattle troughs to cool the radiator. It was a brutal, physical grind. There was no windshield. There was no roof. They were exposed to the sun, rain, and wind for two months straight.

Misconceptions About the Route

A lot of people think they just took a straight shot across the middle of the country. They didn't. They went way north through Oregon and Idaho because the southern routes through the deserts were considered impassable for a car's cooling system. They basically took the long way around just to avoid getting buried in sand.

Even with the northern route, they hit snow in the mountains and deep sand in the flats. It was a navigational nightmare that required constant scouting.

Practical Lessons from the First Road Trip

If you're planning a long-distance drive today, you're obviously not going to be wrapping your tires in rope. But the spirit of Jackson's trip still applies to modern overlanding and road tripping.

Over-prepare for mechanical failure. Even today, if you're hitting remote areas like the Loneliest Road in Nevada (US-50), you need more than just a cell phone.

Don't trust the timeline. Jackson thought he’d be faster. He wasn't. The best road trips are the ones where you allow for the "broken axle" moments—or in modern terms, the "scenic detour that took four hours."

Community is your GPS. Jackson survived because of the kindness of blacksmiths and farmers. If you're off the beaten path, talk to the locals. They know which roads are washed out better than a satellite does.

The Winton "Vermont" now sits in the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. It looks surprisingly small and fragile in person. It’s a reminder that the entire American car culture started with a doctor, a mechanic, and a dog who just wanted to prove that it could be done.

✨ Don't miss: Why the City of Aptos CA is Way More Than Just a Santa Cruz Sidekick

To truly appreciate the history, you should look into the Ken Burns documentary on the subject or visit the Smithsonian's transportation wing. Understanding the sheer lack of infrastructure Jackson faced makes every highway mile we drive today feel like a luxury.

Take Actionable Steps for Your Next Trip:

- Check your tire pressure and fluid levels before any trip over 300 miles; Jackson would have killed for a reliable radiator.

- Carry a physical atlas. Tech fails in the mountains, just like Jackson's Winton failed in the Sierras.

- If you're traveling with a pet, invest in high-quality eye protection or sun-shading if you're in an open-top vehicle or hitting high-dust areas. Bud would approve.