When the ground starts rolling, the first thing everyone asks is a variation of the same question: how big was the earthquake? We want a single number. We want a 7.2 or a 5.8 or an 8.1. It’s a human instinct to categorize chaos. We need a way to measure the monster that just shook our walls and rattled our nerves. But honestly, that single number you see scrolling across the bottom of the news ticker is often misleading. It's just one piece of a much larger, much more violent puzzle.

Earthquakes are tricky.

You can have a "huge" earthquake that kills nobody and a "small" one that levels a city. If you’re looking at the raw data, "bigness" is a bit of a loaded term. To a seismologist at the USGS, how big was the earthquake refers to the total energy released at the source—the moment magnitude. But to the person standing in a kitchen in Los Angeles or Tokyo, "how big" is about how much the floor moved and whether the roof stayed on.

The Richter Scale is Dead (And Why We Still Use It)

Most people still say "Richter Scale." It’s stuck in our collective vocabulary like an old song lyric. But here’s the thing: scientists haven't really used the Richter Scale for large, global earthquakes since the 1970s. Charles Richter developed his scale in 1935 specifically for Southern California. It was designed for a certain type of seismograph and a certain type of rock. It’s basically the "analog" version of earthquake measurement.

When we talk about massive events today, like the 2011 Tohoku quake in Japan or the 2023 disaster in Turkey and Syria, we’re actually using the Moment Magnitude Scale (Mw).

👉 See also: Wellington Daily News Obituaries: Why Finding Local Records Is Still Kinda Tricky

Why does this matter? Because the Richter scale "saturates." Imagine trying to measure the volume of a rock concert with a microphone that maxes out at a certain decibel. No matter how much louder the band gets, the microphone just shows the same peak level. That’s what happened with Richter. Once an earthquake gets above a certain size, the Richter scale can't tell the difference between a "big" one and a "catastrophic" one. The Moment Magnitude Scale fixes this by looking at the physical size of the fault that slipped and the "stiffness" of the rocks. It measures the actual work done by the earth.

Magnitude vs. Intensity: The Great Confusion

If you want to understand how big was the earthquake, you have to separate Magnitude from Intensity.

Magnitude is the size of the earthquake at its source. It’s like the wattage of a lightbulb. A 100-watt bulb is always a 100-watt bulb. Intensity, however, is what you feel. If you’re standing right next to that 100-watt bulb, it’s blinding. If you’re a mile away, it’s a tiny flicker.

We use the Modified Mercalli Intensity (MMI) Scale for this. It uses Roman numerals (I to XII).

- An MMI IV feels like a heavy truck striking the building.

- An MMI IX means buildings are shifting off their foundations.

This is why a magnitude 6.0 in a place with poor building codes and shallow soil—like the 2010 Haiti earthquake—can be a world-ending event, while a 6.0 in a remote part of Alaska might not even make the evening news. The Haiti quake was "smaller" than many others that year, but its intensity in populated areas was off the charts. It was shallow. It was right under people's feet. It felt "bigger" because it was closer.

The Logarithmic Trap: A 7 is Not Just "One More" Than a 6

Math is usually boring, but this part is terrifying. The magnitude scale is logarithmic. This means that for every whole number you go up, the ground motion increases by 10 times. But the energy release? That increases by about 32 times.

Think about that.

A magnitude 7.0 earthquake isn't just "a little bit stronger" than a 6.0. It releases 32 times more energy. If you move from a 5.0 to a 7.0, you aren't doubling the power; you’re looking at an earthquake that is over 1,000 times more powerful ($32 \times 32$).

Let’s look at the 1960 Valdivia earthquake in Chile. It was a 9.5. To this day, it’s the largest ever recorded. To put that in perspective, a 9.5 is so massive that it literally makes the entire planet ring like a bell for days. If you compare a 9.5 to a "standard" 5.0 earthquake that might rattle your windows, the 9.5 is releasing millions of times more energy. It’s the difference between a hand grenade and a nuclear stockpile.

Why Shallow Quakes Are the Real Killers

When you see a report on how big was the earthquake, look for the depth. This is the "hypocenter."

A magnitude 8.0 that happens 300 miles underground (deep in the mantle) might cause some swaying, but much of that energy is absorbed by the earth before it hits the surface. However, a magnitude 6.5 that happens only 5 miles deep is a nightmare.

The 1994 Northridge earthquake in California was "only" a 6.7. But it was shallow and it happened directly under a major metropolitan area. It produced some of the highest ground accelerations ever recorded in an urban setting. People were literally thrown out of their beds. The "bigness" here wasn't about the total energy released globally; it was about the concentration of that energy in a tiny, shallow space.

The Role of Soil (Liquefaction is Scary)

The ground isn't just "the ground."

Sometimes, the earth behaves like a liquid. This is called liquefaction. If you’re on solid granite, you’re in good shape. The seismic waves pass through quickly. But if you’re on soft, water-saturated silt or reclaimed land—think San Francisco’s Marina District or parts of Mexico City—the ground acts like a bowl of Jell-O.

In the 1985 Mexico City earthquake, the city was hundreds of miles away from the epicenter. By the time the waves reached the city, they should have weakened. Instead, the ancient lakebed sediments the city is built on actually amplified the shaking. The buildings started swaying at the same frequency as the seismic waves. It was a perfect, deadly resonance.

So, when someone asks how big was the earthquake, the answer should probably include: "What were you standing on?"

What About the "Big One"?

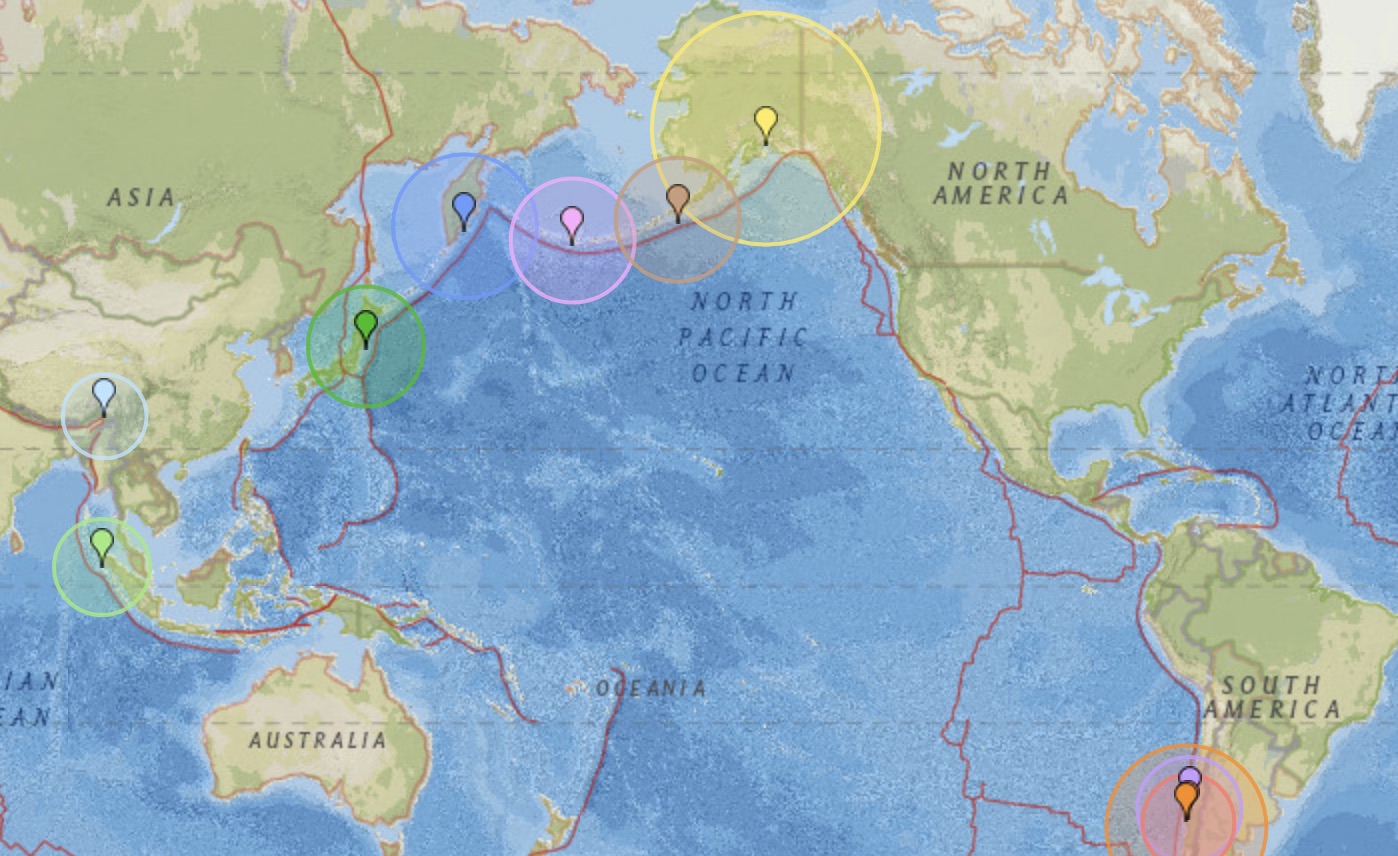

We talk about the San Andreas Fault or the Cascadia Subduction Zone as if they are ticking clocks. In a way, they are. But "the Big One" is a bit of a misnomer. In California, a 7.8 or 8.0 is considered the likely "Big One." In the Pacific Northwest, they are looking at a potential 9.0 from the Cascadia fault.

The difference in "bigness" here is the duration.

A magnitude 6.0 earthquake usually lasts a few seconds. Maybe ten. You feel it, you get scared, it’s over. A magnitude 9.0 can last for five minutes. Imagine the world shaking violently enough to collapse bridges, and it doesn't stop for 300 seconds. That duration is what causes the real structural failure. Buildings can often survive a short, sharp shock. They cannot survive being flexed back and forth for several minutes straight.

Actionable Steps: How to Actually Prepare

Knowing how big an earthquake was is great for trivia, but it doesn't save lives. Understanding your local risk does. Here is what you should actually do with this information.

Check Your Geology

Don't just look at a general map. Go to the USGS website or your local geological survey and look at "Site Class" maps. Find out if you are on "Type D" or "Type E" soil (soft soil and muck). If you are, you need to be much more concerned about earthquake bracing than someone on "Type A" (hard rock).

Forget the Doorway

That’s old advice. Don’t stand in a doorway. In modern houses, the doorway isn't any stronger than the rest of the wall, and the door might swing shut and crush your fingers. The gold standard is Drop, Cover, and Hold On. Get under a sturdy table. Protect your head.

Secure Your "Big" Stuff

Earthquakes don't usually kill people; falling objects do. Look at your water heater. Is it strapped to the wall? If not, it will tip over, break the gas line, and start a fire. Look at your bookshelves. In a 6.0, they become projectiles. Buy some $10 furniture straps. It’s the cheapest life insurance you’ll ever get.

Understand Your Utility Shut-offs

If a big quake hits, you need to know how to turn off your gas. But here’s the expert tip: only turn it off if you actually smell gas or hear a hissing sound. If you turn it off "just because," it might take the gas company weeks to come out and turn it back on for you.

The Reality of the 72-Hour Kit

Most people have a backpack with some granola bars. That’s not enough. After a truly "big" earthquake, emergency services will be overwhelmed. You need to be self-sufficient for at least a week, not three days. This means one gallon of water per person, per day. If you have a family of four, that’s 28 gallons of water just to survive a week. Start stocking up now.

Earthquakes are inevitable, but disasters aren't. The magnitude is just a number. Your preparation is what determines whether that number is a news story or a tragedy.

Key Takeaways for Future Events

- Magnitude measures energy: A 7.0 is 32 times more powerful than a 6.0.

- Intensity measures impact: This is what matters to you on the ground.

- Depth is crucial: Shallow quakes (0-20km) are generally much more destructive than deep ones.

- Soil type can amplify shaking: Being on soft soil can make a medium quake feel like a massive one.

- Duration kills: Large magnitude quakes last much longer, leading to more structural collapses.

Stop focusing only on the number and start looking at the context. The next time you hear a report and ask how big was the earthquake, check the depth and the proximity to city centers first. That will tell you the real story.

Next Steps:

Go to the USGS Earthquake Hazards Program website and search for your specific zip code. Look for "ShakeMaps" of historical quakes in your area. This will give you a realistic idea of what your specific neighborhood might experience during the next significant event. Once you know your risk level, prioritize retrofitting your home, starting with the foundation bolts and the water heater. Knowing the science is the first step, but physical reinforcement is what keeps the roof over your head.