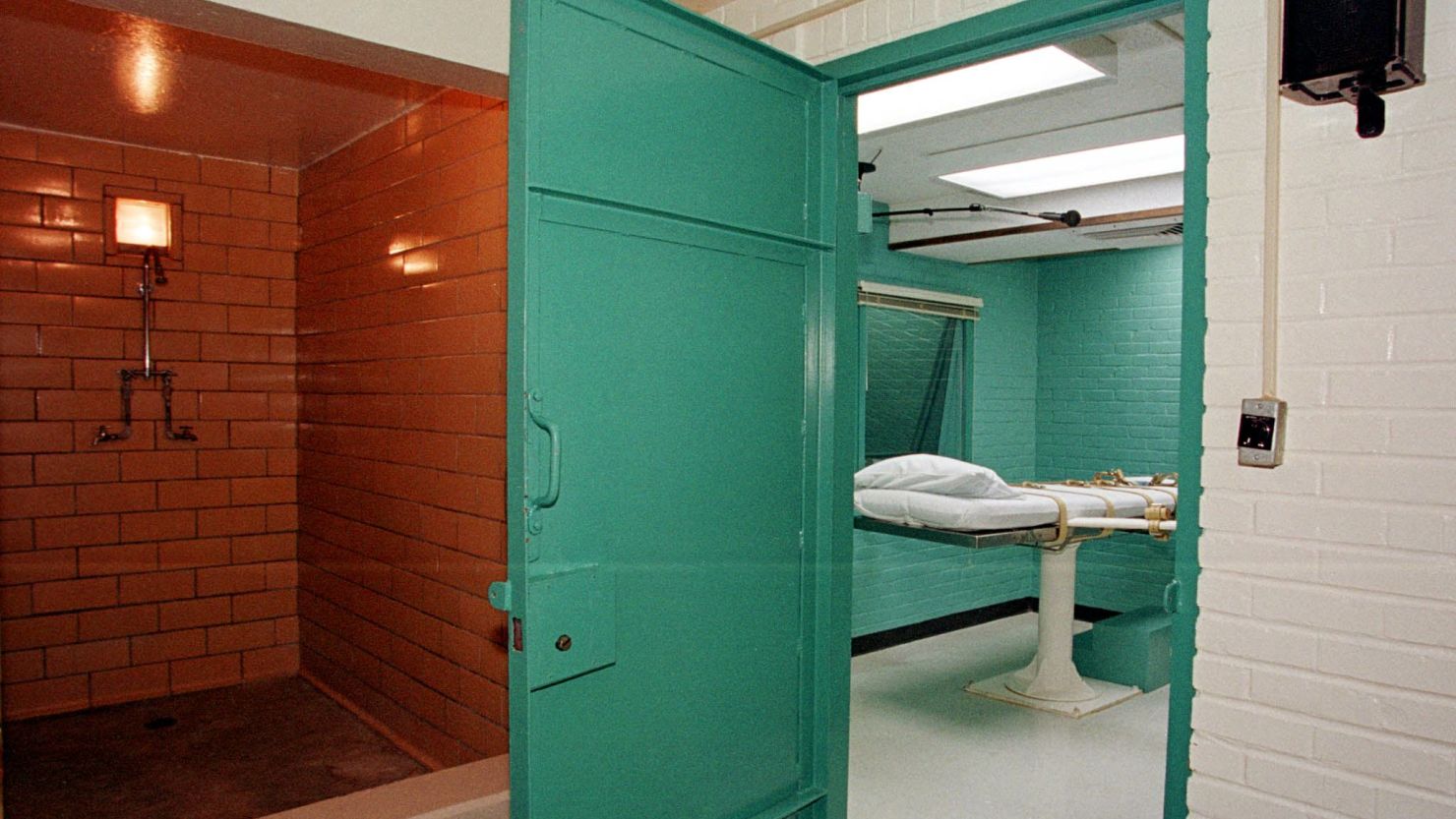

Death is usually a quiet thing in the sterile, beige-walled execution chambers of the United States. It's meant to look like a medical procedure. That’s the whole point of using needles instead of a gallows or an electric chair. But when you ask how long does lethal injection take to work, the answer isn't a single number on a stopwatch. It’s a messy range that depends on the drugs used, the person on the gurney, and whether the execution team can actually find a vein.

Technically, if everything goes according to the manual, a person should be dead in about 10 to 15 minutes.

That is the "textbook" version. In reality, it can take much longer. Sometimes it’s over in seven minutes. Other times, it stretches into a harrowing hour-long ordeal that leaves lawyers frantically filing stay of execution motions while the prisoner is still alive. It’s unpredictable. Honestly, the variability is one of the reasons the death penalty is such a massive legal lightning rod right now.

The Three-Drug Cocktail vs. The One-Drug Method

For decades, the standard was a three-drug sequence. You start with an anesthetic like sodium thiopental or midazolam to knock the person out. Then comes vecuronium bromide to paralyze the muscles. Finally, potassium chloride stops the heart. If the first drug works, the prisoner feels nothing. If it doesn't? They’re awake but paralyzed while their heart stops. That's a terrifying thought.

💡 You might also like: St. Louis MO Earthquake: What Most People Get Wrong About the Big One

The timing here is staggered.

- The Sedative: Takes effect in 30 to 60 seconds.

- The Paralytic: Administered a few minutes later.

- The Heart-Stopper: The final blow.

Because of drug shortages—mostly because European pharmaceutical companies refuse to sell their products to executioners—many states have switched to a single-drug method. They use a massive overdose of a sedative like pentobarbital. This is basically how veterinarians put pets to sleep. It’s slower. It doesn't stop the heart instantly; it just suppresses the central nervous system until the lungs stop moving and the heart eventually gives up. When using pentobarbital, the process usually takes about 15 to 25 minutes from the start of the infusion.

Why Midazolam Changed the Timeline

Midazolam is a sedative, not an anesthetic. That’s a huge distinction. It’s used in dentistry to make you groggy, but it has a "ceiling effect." At a certain point, giving more of it doesn't make you "more" unconscious.

When states started using midazolam, the timeline for how long does lethal injection take to work got weird. We saw cases like Joseph Wood in Arizona back in 2014. It took him nearly two hours to die. He gasped and snorted for 117 minutes. The state’s lawyers argued he was unconscious and "snoring," but witnesses described it as a struggle for breath. Then there was Clayton Lockett in Oklahoma. His vein collapsed, the drugs went into his tissue instead of his bloodstream, and he ended up dying of a heart attack 43 minutes after the process started.

These aren't just "glitches." They are the direct result of how the body reacts to specific chemicals under extreme stress.

The IV Line: The Biggest Variable in the Room

Most people think the timer starts when the chemicals hit the blood. But for the person on the gurney, the "execution" starts when the IV team enters the room. This is where the clock really slows down.

Execution teams aren't usually doctors or nurses. Major medical associations, like the American Medical Association (AMA), forbid their members from participating in executions because it violates the "do no harm" oath. So, you have technicians—sometimes with questionable training—trying to find veins in people who might have a history of IV drug use or who are simply dehydrated and terrified.

In Alabama, the execution of Kenneth Smith (before they eventually used nitrogen gas) was called off because they spent over an hour poking him with needles and couldn't find a vein. If you count that "prep time," the process can take hours before a single drop of poison is even administered.

Does Weight or Health Affect the Speed?

Absolutely. Metabolism plays a role. If a prisoner has a high tolerance to opioids or benzodiazepines, the initial sedative might not "take" as quickly. A larger body mass might require a higher dose to reach the brain effectively. However, the doses used in lethal injections are typically "supratherapeutic"—meaning they are way more than what is needed to kill a human being—so biological resistance is usually less of a factor than the delivery method itself.

The environment matters too. The "death house" is cold. Stress causes veins to constrict. If the prisoner's blood pressure is spiking, it can actually change how the drugs circulate. It’s a physiological paradox: the more the body fights to stay alive, the more complicated the process of ending it becomes.

Legal Definitions of "Quick" and "Painless"

The Eighth Amendment prohibits "cruel and unusual punishment." The Supreme Court has ruled that an execution doesn't have to be totally painless to be constitutional, but it can't involve "wanton and unnecessary" pain.

Because of this, states are very careful about how they record time. If you look at official logs, they often list the "start time" as when the drugs begin to flow and the "end time" as when a physician declares death. This ignores the 45 minutes of searching for a vein or the 10 minutes of "consciousness checks" where guards shout the prisoner's name and flick their eyelids.

Real-World Timelines: A Comparison

If you look at the data from the Death Penalty Information Center, the averages vary by state and drug protocol:

- Texas (Pentobarbital): Generally very efficient, often under 20 minutes.

- Ohio (Variable protocols): Historically longer, with several botched attempts exceeding 30 minutes.

- Oklahoma (Midazolam cocktail): Has seen some of the longest durations in modern history.

The speed is often tied to the "efficiency" of the state’s team. Texas has a very practiced rhythm because they carry out more executions than anyone else. But even a practiced team can't account for a "blown vein" or a drug that doesn't react the way the chemistry books say it should.

The Move Away from Injection

Because of the questions surrounding how long does lethal injection take to work, we are seeing a shift. States are looking for "fail-proof" methods. Alabama recently used nitrogen hypoxia, which involves breathing pure nitrogen through a mask. The theory was that it would be faster and "cleaner."

In the first nitrogen execution, the prisoner appeared to struggle and shake for several minutes. It didn't necessarily solve the "time" problem; it just moved the problem from the veins to the lungs.

Navigating the Facts of Lethal Injection

If you are researching this for a legal, academic, or journalistic reason, it’s vital to distinguish between the "official" report and the "eyewitness" account. Media witnesses often report gasping, chest heaving, or movement that the official state logs don't mention.

- Check the Drug Protocol: Different drugs have different onset times. Pentobarbital is slow but steady; Midazolam is fast but unpredictable.

- Look at the "Start" Definition: Always ask if the reported time includes the setting of the IV lines.

- Verify the Source: State Department of Corrections (DOC) websites provide the "official" time, while organizations like the ACLU or DPIC often provide a more critical breakdown of the events.

Ultimately, the answer to how long the process takes is that it takes as long as the chemistry allows and the anatomy permits. It is a medicalized process performed by non-medical personnel, and that inherent contradiction is why the clock never seems to run the same way twice.

For those tracking the legal implications of these timelines, the focus should remain on the "consciousness check" phase. This is the critical window where the most legal challenges occur—if a prisoner is still responsive after the first round of drugs, the entire protocol is usually deemed a failure in the eyes of the court. Understanding these nuances is the first step in grasp of the current state of capital punishment in the U.S.