You're standing in a hardware store aisle or staring at a 3D printer blueprint, and the numbers just aren't clicking. We've all been there. It’s that moment of friction where the American imperial system bumps into the metric system used by literally almost everyone else on the planet. You need to know exactly how many millimeters is an inch to keep your project from falling apart.

Exactly 25.4.

That’s the magic number. It isn't an approximation. It isn't a "close enough" rounding situation. Since the International Yard and Pound Agreement of 1959, the inch has been physically defined by the metric system. One inch is exactly $25.4\text{ mm}$. No more, no less. If you’re working on something where precision matters—like engine machining or jewelry making—that decimal point is your best friend.

Why 25.4 is the number that rules the world

It feels a bit random, doesn't it? Why not a clean 25? To understand why we use this specific conversion, you have to look back at the chaotic history of measurement. Before 1959, the United States and the United Kingdom actually had slightly different definitions of an inch.

Can you imagine the nightmare?

A tool made in London might not fit a bolt made in New York, even if they were both labeled as the same size. It was a mess for international trade. The 1959 agreement fixed this by tethering the inch to the millimeter. By defining an inch as exactly $2.54\text{ centimeters}$ (which is $25.4\text{ mm}$), the world finally had a single, unified standard.

This number is the bridge. It allows a designer in California to send a file to a factory in Shenzhen and expect the parts to fit. If you're wondering how many millimeters is an inch because you're DIYing a home repair, you can usually round to 25 for a "rough estimate," but you'll regret it if you're hanging a heavy cabinet or cutting glass.

The math in your head

Most people hate doing mental math with decimals. I get it. If you need a quick mental shortcut, think of it this way: an inch is a bit more than two and a half centimeters.

If you have 2 inches, you’ve got about 50 mm ($50.8\text{ mm}$ to be precise).

If you have 4 inches, you're looking at roughly 100 mm ($101.6\text{ mm}$).

Honesty time: for most household stuff, being off by that $1.6\text{ mm}$ won't kill you. But if you are working with electronics or mechanical engineering, that tiny gap is the difference between a functional machine and a pile of scrap metal. Professionals use digital calipers for a reason. They don't guess.

Why does the U.S. still use inches anyway?

It’s the question that haunts every science student and immigrant. If the metric system is so much easier—base ten, logical, used by 95% of the world—why are we still stuck with inches, feet, and yards?

The answer is mostly "it's too expensive to change."

Think about the sheer scale of the American infrastructure. Every road sign, every building code, every technical manual for every aircraft and car ever manufactured in the States is written in imperial units. Replacing every bolt in every bridge across the country would cost billions.

Even though the U.S. officially "adopted" the metric system as the preferred system for trade and commerce back in 1975 (The Metric Conversion Act), it was voluntary. Americans just... didn't do it. We like our inches. We like our 2x4s and our 12-inch subs.

But here is the irony. Even if you think you're living in an imperial world, you're secretly living in a metric one. Your soda comes in liters. Your medicine comes in milligrams. And as we established, the very definition of the inch you’re using is based on the millimeter. You're using metric; you're just wearing an imperial costume.

When "close enough" isn't good enough

Let's talk about the Mars Climate Orbiter. This is the ultimate cautionary tale for anyone wondering how many millimeters is an inch and thinking it doesn't matter.

In 1999, NASA lost a $125 million spacecraft. Why? Because one engineering team used metric units while another used imperial units. The software calculated the force the thrusters needed in Newtons (metric), but the piece of equipment providing the data was outputting pound-force (imperial).

The orbiter got too close to the Martian atmosphere and disintegrated.

That is a very expensive math error. While you probably aren't landing a probe on a red planet this weekend, the principle sticks. If you are mixing tools—say, using a metric socket set on an American-made car—you're going to strip some bolts. A 13 mm wrench is almost a 1/2 inch wrench ($12.7\text{ mm}$), but that $0.3\text{ mm}$ difference is enough to ruin your afternoon.

Common conversions you'll actually use

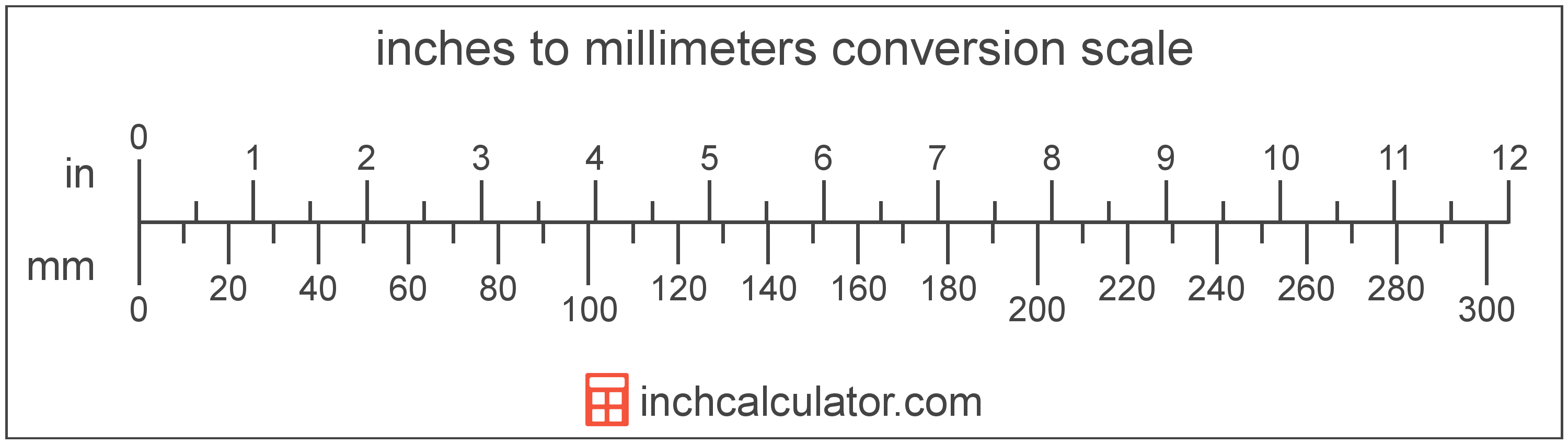

You don't need a table for everything, but a few "anchor points" help keep your brain calibrated.

- 1/8 inch is roughly 3 mm ($3.175\text{ mm}$).

- 1/4 inch is roughly 6 mm ($6.35\text{ mm}$).

- 1/2 inch is exactly 12.7 mm.

- 3/4 inch is roughly 19 mm ($19.05\text{ mm}$).

- 1 inch is 25.4 mm.

Notice how the metric numbers are clean? That’s the beauty of the system. It’s all based on tens. To go from millimeters to centimeters, you just move the decimal. $25.4\text{ mm}$ becomes $2.54\text{ cm}$. Simple. To go from inches to feet to yards? You’re multiplying by 12, then by 3, then by 1,760 for a mile. It’s madness, honestly.

Precision tools and how to read them

If you're serious about your project, stop using a wooden ruler. Standard rulers have a "bleed" at the end, and the markings are often thick enough to throw you off by half a millimeter.

Buy a pair of digital calipers.

✨ Don't miss: Athol ID 83801 Weather: What Most People Get Wrong

You can find a decent pair for twenty bucks. They allow you to toggle between inches and millimeters with the press of a button. This is the "cheat code" for anyone who doesn't want to memorize how many millimeters is an inch. You measure the object, see $25.4$, hit the button, and it tells you $1.00$.

It's also worth noting that in high-precision manufacturing, like making parts for an iPhone or a Tesla, they don't even use inches or millimeters. They use "thous." A "thou" is one-thousandth of an inch ($0.001\text{ inch}$). Even in that microscopic world, the conversion remains fixed. One thou is exactly $0.0254\text{ mm}$.

The psychological hurdle of switching

Most people struggle with metric not because the math is hard, but because they lack a "feel" for the size.

You know what an inch looks like. It's roughly the length of the top joint of your thumb. You know what a foot looks like. But what does $25\text{ mm}$ feel like?

It’s small.

A standard US nickel is about $2\text{ mm}$ thick. A paperclip is about $1\text{ mm}$ wide. If you can visualize 25 paperclips lined up, you're looking at an inch. Once you start visualizing in metric, the need to constantly ask how many millimeters is an inch starts to fade. You just start seeing the world in millimeters.

Actionable steps for your next project

If you are currently staring at a measurement that needs converting, here is exactly what to do to ensure you don't mess it up:

- Use the 25.4 constant: Don't round to 25 unless you're just eyeballing a rug in a living room. For any tool work, use the full decimal.

- Stick to one system: If you start a project in metric, finish it in metric. Mixing and matching is where the "Mars Orbiter" mistakes happen.

- Check your tools: Check if your tape measure has both units. Most do. Use the metric side for more accurate "fine" measurements, as millimeters are smaller than the 1/16th markings on the imperial side.

- Verify the standard: If you're buying parts online, check if they are "True Metric" or "Soft Metric." Soft metric means it was designed in inches but labeled in millimeters (like a $12.7\text{ mm}$ pipe which is actually just a 1/2 inch pipe). True metric means it was designed from scratch on the 10-base system.

The reality is that the inch isn't going anywhere in the U.S. anytime soon. But as the world gets more connected, the ability to jump between $25.4$ and $1$ is a literal survival skill for the modern maker, mechanic, or homeowner. Keep that $25.4$ tucked in your back pocket. It's the only number you really need.

To get the most accurate results in your work, always perform your calculations twice. Once to get the number, and a second time to ensure you didn't accidentally move a decimal point. In the world of measurement, there is no such thing as being too careful.