Ever stared at a ticking clock and wondered how much of your life is actually slipping away in real-time? It’s a bit existential, honestly. Most of us just want the quick answer so we can finish a math problem or win a bar bet. But the truth is, the number of seconds are in a year isn't just one single, static digit that stays the same forever. It depends entirely on which year you’re talking about and how much of a "perfectionist" you want to be about orbital mechanics.

If you’re looking for the standard, "non-leap year" answer, it’s 31,536,000 seconds.

That looks like a lot. It is. But that number is a bit of a lie. It’s a convenient fiction we use to keep our calendars from falling apart, even though the Earth doesn't actually care about our round numbers.

Why the math isn't as simple as you think

Basic multiplication is easy. You take 60 seconds, multiply by 60 minutes, then by 24 hours, and finally by 365 days. $60 \times 60 \times 24 \times 365 = 31,536,000$. Done.

But wait.

The Earth doesn't take exactly 365 days to go around the Sun. It takes roughly 365.24219 days. This is why we have leap years. If we didn't add that extra day every four years, our seasons would eventually drift. In a few centuries, you’d be celebrating Christmas in the blistering heat of July (if you're in the Northern Hemisphere).

So, when we talk about how many seconds are in a year during a leap year, the number jumps. You add an entire extra day’s worth of seconds—86,400 of them—bringing the total to 31,622,400 seconds.

The Gregorgian Average

Since our calendar operates on a cycle where we have three "normal" years and one leap year (mostly), mathematicians and astronomers often use a "mean Gregorian year." This is an average. It assumes a year is exactly 365.2425 days long.

When you do the math on that average, you get 31,556,952 seconds.

If you are writing code or doing high-level physics, that’s usually the number you want. It accounts for the long-term drift. But even then, things get weirder.

📖 Related: Wait, is Rhyming Japanese Philosophy NYT Actually a Thing?

The "Leap Second" Controversy

You might have heard of leap seconds. They are the bane of existence for software engineers at places like Google and Meta. Basically, the Earth’s rotation is slightly irregular. It’s slowing down because of tidal friction caused by the Moon. To keep our ultra-precise atomic clocks in sync with the actual rotation of the planet, the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS) occasionally inserts an extra second into the year.

This usually happens on June 30 or December 31.

When a leap second occurs, that specific year has 31,536,001 seconds (or 31,622,401 if it’s a leap year).

It sounds tiny. It’s one second! But in 2012, a leap second caused Reddit, Yelp, and LinkedIn to crash because their servers couldn't handle the clock "repeating" a second. Because of this chaos, the world’s metrologists actually voted in 2022 to scrap the leap second by the year 2035. We’re basically decided that we’d rather let the clock be slightly wrong than break the internet.

Breaking it down for different contexts

Depending on who you are, the "correct" answer changes.

📖 Related: Why The Dress With Shirt Combo Is Actually A Wardrobe Genius Move

- The Casual Observer: 31.5 million seconds. (Round it off, nobody likes decimals at a party).

- The Student: 31,536,000 seconds. (This is what your teacher wants to see on the test).

- The Astronomer: 31,557,600 seconds. (This is based on the Julian year of 365.25 days).

- The Scientific Purist: 31,556,925 seconds. (The Sidereal year, which is the time it takes Earth to orbit relative to fixed stars).

Honestly, the variation is wild. A Sidereal year is about 20 minutes longer than a tropical year (the one our seasons follow).

How much can you actually do in 31,536,000 seconds?

Numbers that big feel abstract. Let’s make it real.

If you spent every single second of a non-leap year counting out loud, and you somehow never slept or ate, you wouldn't even finish counting to 32 million.

In that same year, your heart will beat roughly 35 to 45 million times. You’ll take about 8 million breaths. If you’re a light traveler, the Earth will have moved about 584 million miles through space in its orbit.

It’s a massive amount of time, yet we always feel like we’re running out of it.

Why we perceive time differently

There's this weird psychological phenomenon where time feels like it speeds up as you get older. When you are 5 years old, one year is 20% of your entire life. Those 31 million seconds feel like an eternity. When you’re 50, a year is only 2% of your life. The seconds don't change, but your "denominator" does.

This is why "seconds in a year" is a popular search term for people trying to visualize productivity. We want to know how many chunks of time we have to work with. If you sleep 8 hours a day, you’re instantly losing 10,512,000 seconds to the pillow.

Practical Math: Converting units fast

Sometimes you just need the conversion factors without the fluff. If you're building a spreadsheet or a countdown timer, keep these constants in mind:

- Minute: 60 seconds

- Hour: 3,600 seconds

- Day: 86,400 seconds

- Week: 604,800 seconds

- Month (Average): 2,629,746 seconds

Don't bother memorizing the month one. It’s useless because months are irregular. February is the "short" month that ruins every developer's Friday afternoon.

✨ Don't miss: Spring Break Nail Ideas That Actually Last Through Sand and Saltwater

Moving forward with your time

Knowing exactly how many seconds are in a year is a great trivia fact, but it's more useful as a tool for perspective. Whether you're calculating the return on an investment, programming a precise piece of software, or just trying to wrap your head around the scale of your life, remember that the "standard" number is just a baseline.

If you are working on a project that requires extreme precision—like GPS synchronization or high-frequency trading—always use the Julian Year ($31,557,600$ seconds) or the Gregorian Mean. For everything else, the standard 31,536,000 works just fine.

Next Steps for Accuracy:

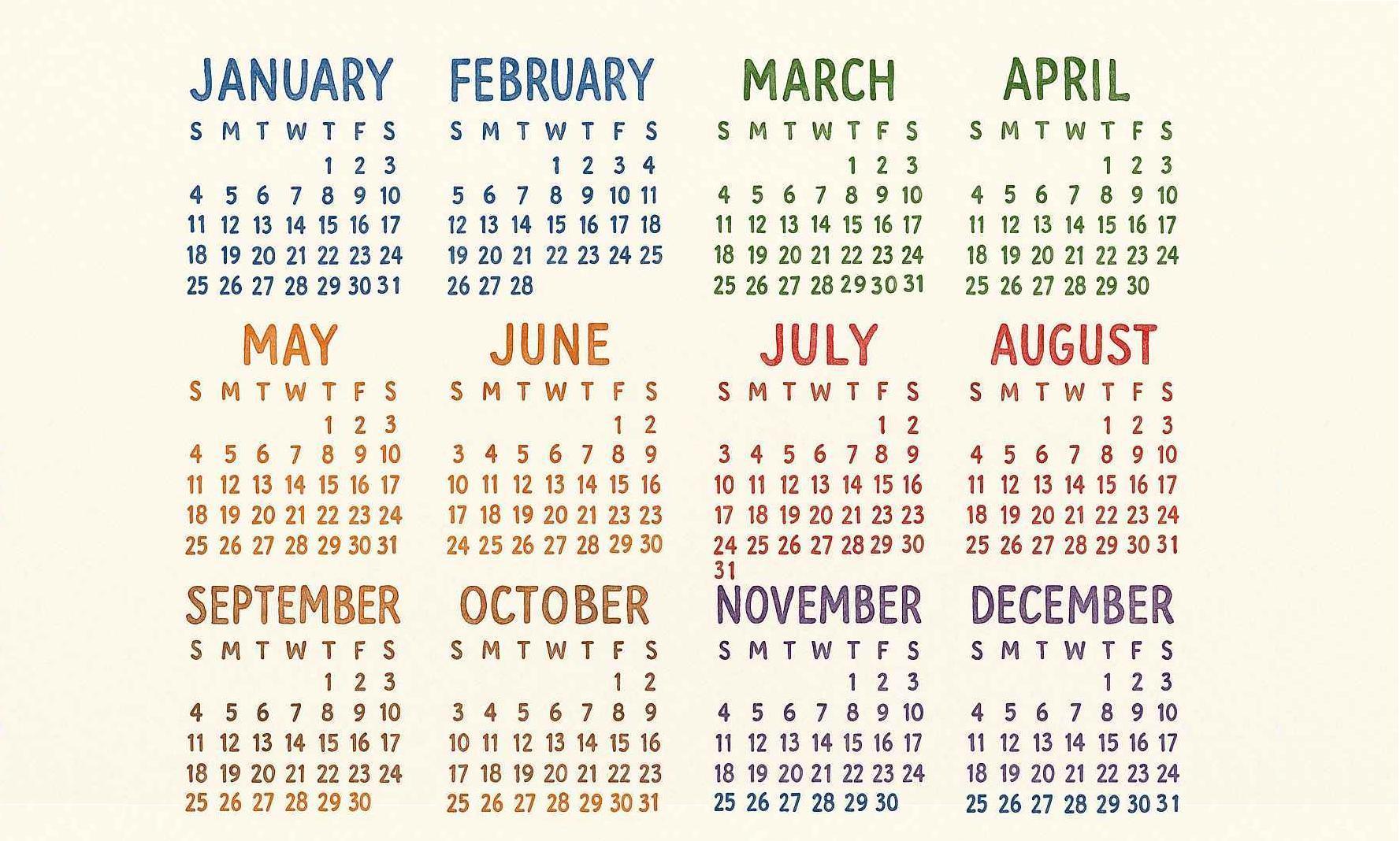

- Check if the current year is a leap year (divisible by 4, but not by 100, unless also divisible by 400).

- If you're coding, use built-in library functions like Python's

datetimeor JavaScript'sDateobject instead of hard-coding the seconds. They handle the leap year logic for you. - If you're curious about the exact moment the Earth completes its orbit, look up the "Vernal Equinox" times for the current year, as the orbital speed actually fluctuates slightly.