Peter Boyle was terrified of being "the big guy." Before he stepped onto the set of Mel Brooks’ 1974 masterpiece, he was mostly known for playing Joe, a hateful, blue-collar bigot. He didn't want to be a prop. He wanted to be a person. What we eventually got with Peter Boyle in Young Frankenstein wasn't just a parody of Boris Karloff; it was a masterclass in physical comedy that somehow managed to be heartbreaking and hilarious at the exact same time.

Most people remember the singing. They remember the top hat. They remember the "Puttin' on the Ritz" routine that probably shouldn't have worked but became one of the most iconic moments in cinema history. But if you look closer, there is a weird, soulful depth to Boyle’s performance that makes the movie stick in your brain long after the credits roll. He wasn't just a monster. He was a misunderstood toddler in the body of a giant, and that specific choice is why the film still feels fresh fifty years later.

The Monster Who Just Wanted a Hug

Gene Wilder actually wrote the role with Peter Boyle in mind, which is kind of wild when you think about it. Boyle had this incredible ability to look intimidating while projecting a sense of total vulnerability. In the original 1931 Frankenstein, the creature is a tragic figure, sure, but Boyle takes that tragedy and turns it into a comedic engine.

Think about the scene with the blind hermit, played by an uncredited Gene Hackman. It’s a sequence that could have been a one-note joke about a guy who can't see. Instead, because of how Boyle reacts—his whimpering when the hot soup is poured on him, the way he gingerly holds a wine glass—it becomes a comedy of manners. Boyle plays the "Monster" as a man desperately trying to be polite in a world that keeps accidentally setting him on fire. It’s brilliant.

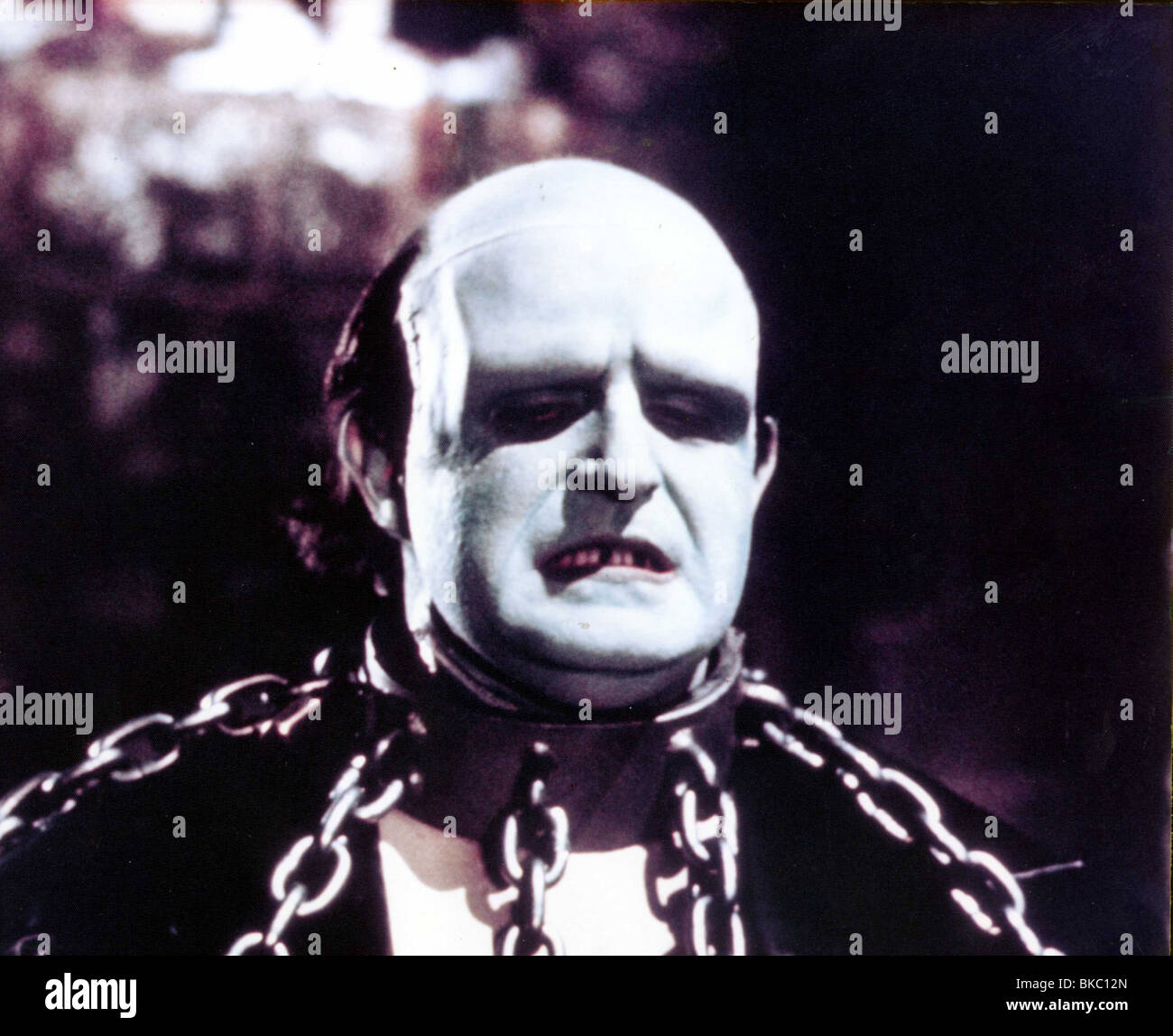

He had to sit through hours of makeup every single day. Green greasepaint. A prosthetic forehead. Those neck bolts. Yet, despite being buried under layers of rubber and paint, his eyes do all the heavy lifting. You can see the confusion. You can see the flashes of joy when he realizes someone isn't screaming at him. Honestly, most actors today struggle to show that much emotion with their whole face visible, let alone behind a mask.

Why the "Puttin' on the Ritz" Scene is Geniunely Important

If you haven't seen the tap-dancing scene in a while, go watch it again. It’s not just funny because a monster is dancing. It’s funny because of the power dynamic. Dr. Frederick Frankenstein (Wilder) is trying to prove his creation is a sophisticated "man about town," while Boyle’s creature is clearly just trying his best to remember the steps.

The contrast in their voices is the kicker. Wilder is singing in a polished, theatrical tenor. Boyle? He’s let out these guttural, screeching yelps that barely resemble the lyrics. It’s a high-wire act. If Boyle had played it too "smart," the joke would have died. If he played it too "dumb," it would have been offensive or boring. He found the sweet spot: the monster as a proud performer.

- The scene was almost cut.

- Mel Brooks thought it was too silly.

- Gene Wilder fought for it for days until Brooks relented.

- Boyle actually learned the choreography despite the platform shoes.

The shoes were actually a massive challenge. He was wearing heavy, four-inch lifts to make him tower over the rest of the cast. Try doing a soft-shoe routine in those. It’s a miracle he didn't break an ankle, but that clunky, weighted movement actually added to the character’s charm. He moved like a skyscraper trying to be a ballerina.

🔗 Read more: Why Diane Keaton Something's Gotta Give Still Matters: What Most People Get Wrong

The Makeup and the Method

Boyle wasn't a "method" actor in the traditional sense, but he stayed in a weird headspace on set. He realized early on that the monster is essentially a newborn. He doesn't have a vocabulary. He doesn't understand social cues. So, Boyle stopped using words between takes sometimes. He would just grunt or point.

The makeup itself was designed by William Tuttle, a legend in the industry. They purposefully went for a look that honored the 1931 original but felt slightly "off." The skin was a pale, sickly grey-green that looked amazing in the high-contrast black and white cinematography. Using black and white was a huge risk in 1974. Most studios hated the idea. But Brooks insisted, and it was the right call. It made Peter Boyle in Young Frankenstein look like he had literally stepped out of a time capsule.

Interestingly, the zippers on his neck weren't just a visual gag. They represented the "patchwork" nature of the man. Boyle played into that physical disjointedness. His walk was stiff-legged, not because he was a zombie, but because his parts didn't quite fit together yet. It’s a subtle distinction that a lesser actor would have missed.

Dealing With the "Joe" Reputation

Before this film, Boyle was frequently accosted in the street by people who thought he actually was the violent, racist character he played in Joe (1970). It took a toll on him. He actually turned down a lot of "tough guy" roles because he didn't want to be associated with that energy.

🔗 Read more: How a Star Wars Wanted Poster Became the Ultimate Fan Collectible

Young Frankenstein was his pivot. It allowed him to show his range. It proved he could be the lead in a comedy. It also allowed him to work with his best friend, Gene Wilder. The chemistry between them wasn't faked; they genuinely loved each other. You can see it in the "Sedagive" scene. When Wilder is pinning Boyle to the wall, trying to inject him with a sedative, the frantic energy is real. They were trying to make each other crack up constantly.

The Legacy of a Gentle Giant

When we talk about the greatest comedic performances of all time, Boyle’s name usually comes up, but often as a supporting player. That’s a mistake. He is the heart of the movie. Without his vulnerability, the movie is just a series of dick jokes and puns. With him, it’s a story about a "father" and "son" trying to find a middle ground.

Even later in his career, when he became famous for Everybody Loves Raymond, you could still see glimpses of the Monster. That deadpan delivery? That ability to look completely done with the world while still being lovable? That started in 1890s Transylvania (or at least the 1974 version of it).

How to Appreciate the Performance Today

If you want to really "get" what Boyle did, you have to watch the film with the sound off for ten minutes. Just watch his face. Watch how he reacts to the fire. Watch the way his lip quivers when he’s sad.

Take these steps to see the nuance:

💡 You might also like: Wait, Is Upa Actually in Dragon Ball Z? Clearing Up the Confusion

- Watch the 1931 original first. You need to see Karloff to understand what Boyle is subverting.

- Focus on the eyes. Ignore the bolts and the hair. Just look at his pupils.

- Listen to the breathing. Boyle uses heavy breathing and small whimpers to communicate more than the dialogue ever could.

- Look for the "tells." He has small physical tics—like the way he fumbles with his hands—that suggest a nervous system that isn't fully calibrated.

Peter Boyle didn't just play a monster; he played a man who was built from the ground up and was doing his best with the hand he was dealt. He was the "zipper-necked" soul of the movie. Without his specific brand of weird, intellectual physical comedy, Young Frankenstein would just be another parody. Instead, it's a classic.

To truly understand the impact of this role, your next move is to find the behind-the-scenes footage of the "Puttin' on the Ritz" rehearsals. Seeing Boyle out of makeup, practicing the steps with Wilder, reveals the sheer technical discipline required to make "clumsy" look that effortless. From there, compare his physical timing to his later work in the 90s; you'll see a direct line from the Monster's grunts to Frank Barone's legendary deadpan.