It’s easy to think of the making of an atomic bomb as a single, Eureka-style moment in a desert lab. People imagine Oppenheimer standing over a desk, scribbling an equation, and—boom—the world changes. But that’s mostly Hollywood. The reality was a messy, terrifyingly expensive industrial slog that involved more plumbers and construction workers than it did Nobel Prize winners.

Actually, it was the biggest construction project in human history.

Think about this: at its peak, the Manhattan Project employed about 130,000 people. That is roughly the population of a mid-sized city like Hartford or New Haven, all working on a secret they weren't allowed to talk about. Most of them had no idea what they were building. They were just turning dials, hauling pipes, and living in muddy, temporary towns built from scratch in Tennessee and Washington state.

✨ Don't miss: Is AT\&T Network Down? Why Your Phone Is a Paperweight and How to Fix It

The Problem Wasn't Just the Science

Everyone knew the theory. By 1939, after Lise Meitner and Otto Frisch figured out nuclear fission, the physics were basically out in the open. You hit a heavy atom with a neutron, it splits, it releases energy, and it tosses out more neutrons to keep the party going. Simple, right?

Not really.

The nightmare was the fuel. To get a chain reaction, you need a very specific kind of uranium—U-235. The problem is that 99% of the uranium you dig out of the ground is U-238, which is useless for a bomb. They are chemically identical. You can't just use a chemical reaction to separate them. It’s like trying to find a few specific grains of sand in a giant bucket where every grain looks and weighs almost exactly the same.

This is where the making of an atomic bomb shifted from a physics problem to an industrial nightmare.

The Ridiculous Lengths of Oak Ridge

The government built a massive plant in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, called K-25. At the time, it was the largest building in the world under one roof. It used a process called gaseous diffusion. Essentially, they turned uranium into a corrosive gas and pumped it through miles of silver-plated barriers with tiny holes. The lighter U-235 moved just a tiny bit faster.

You had to do this thousands of times.

It was incredibly inefficient. General Leslie Groves, the guy in charge of the whole project, was also building a backup plan at the same time: electromagnetic separation. This involved using massive magnets to pull the uranium atoms apart. But there was a massive copper shortage because of the war. So, what did the Army do? They went to the U.S. Treasury and "borrowed" nearly 15,000 tons of silver. They melted it down into wire for the magnets.

Imagine being a Treasury official and having a General show up asking for 400 million ounces of silver for a project he can't explain. That's the level of desperation we're talking about.

The Plutonium Shortcut

While the folks in Tennessee were struggling with uranium, another group in Hanford, Washington, was trying something even weirder. They were making a brand-new element: Plutonium.

Plutonium doesn't really exist in nature. You have to cook U-238 in a nuclear reactor until it transmutes. It was a gamble. Nobody knew if they could even produce enough of it to matter. But plutonium is way more "potent" than uranium. You need less of it to get an explosion.

The B Reactor at Hanford was the first large-scale nuclear reactor ever built. It leaked. It broke down. It almost got shut down because of a weird phenomenon where the reactor would just "poison" itself and stop working (it turned out to be Xenon buildup). But they pushed through because the uranium process was moving too slowly.

Los Alamos: The Brains in the Mud

While the factories were churning out fuel, the "scientists" were stuck on a mesa in New Mexico. Los Alamos was basically a high-pressure pressure cooker for geniuses. You had Richard Feynman, Enrico Fermi, and Robert Oppenheimer all living in cramped quarters, arguing over how to actually make the fuel go "bang" at the right millisecond.

There are two ways to do it.

- The Gun Method: You fire one piece of uranium into another. This is what they used for the "Little Boy" bomb. It was so simple they didn't even bother testing it before they used it.

- Implosion: This is the hard part. You take a sphere of plutonium and surround it with high explosives. You have to detonate those explosives so perfectly that they squeeze the plutonium inward from all sides simultaneously.

If your timing is off by even a fraction of a microsecond, the whole thing just "fizzles." It’s like trying to squeeze a balloon with your hands so perfectly that it gets smaller without popping between your fingers.

They had to invent entirely new types of detonators and "explosive lenses" to make this work. This was the focus of the Trinity Test—the first actual detonation of a nuclear device in July 1945. They weren't testing the uranium bomb; they were testing the implosion mechanism because it was so damn complicated they weren't sure it would work at all.

What Most People Miss About the Cost

People talk about the $2 billion price tag. In 1940s money, that was astronomical. But it wasn't spent on "science."

Most of that money went into:

- Concrete and steel.

- Electricity (at one point, the Manhattan Project used about 10% of the entire electrical output of the United States).

- Housing for tens of thousands of workers who weren't allowed to know what they were building.

The making of an atomic bomb was more about logistics than it was about E=mc². Without the massive industrial might of the U.S. car and chemical industries, the physics would have just stayed on a chalkboard.

The Ethical Ghost in the Machine

We can't talk about the technical side without acknowledging that the people involved were terrified. They weren't just "building a tool." They were racing against a Nazi nuclear program that they thought was much further along than it actually was.

By the time the bomb was ready, Germany had already surrendered.

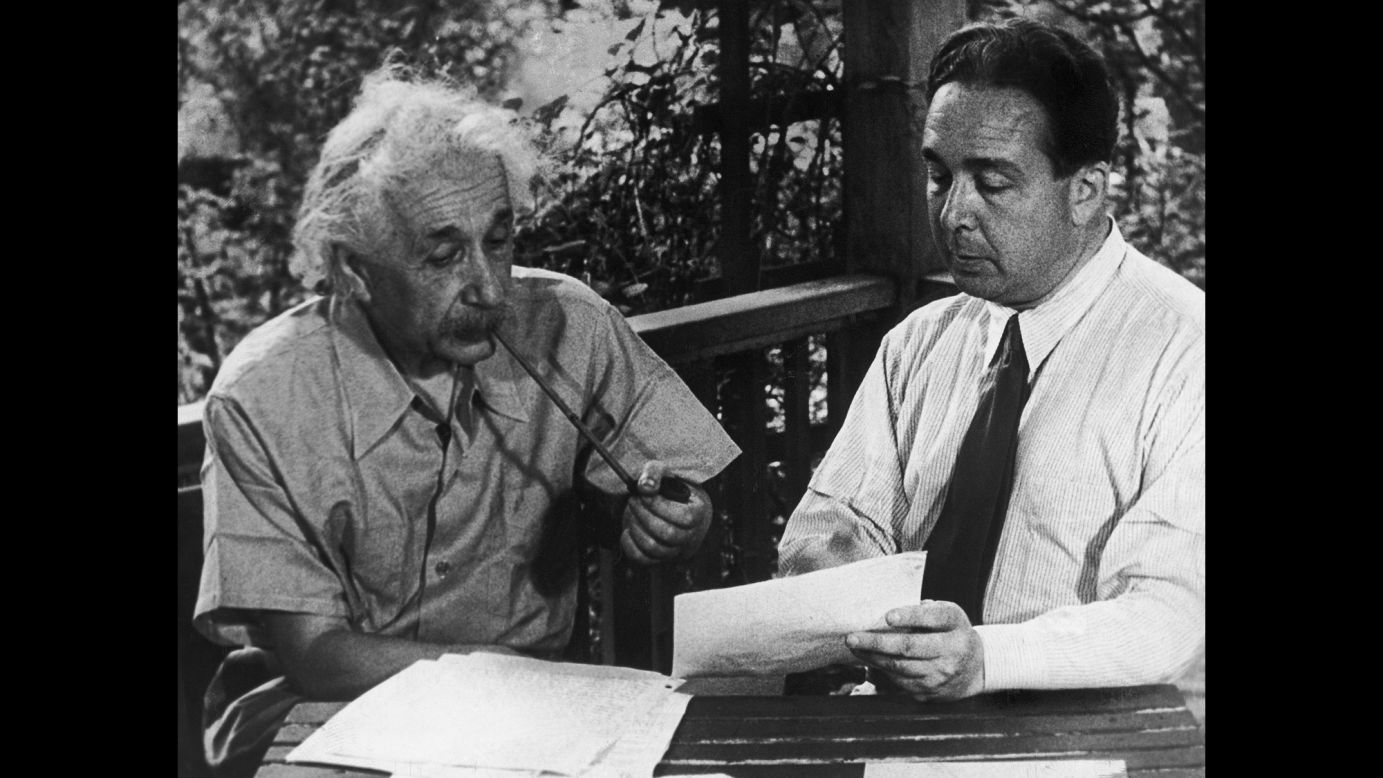

This shifted the entire dynamic. Some scientists, like Leo Szilard (who actually came up with the idea of the chain reaction), tried to stop the bomb from being used on a city. They argued for a "demonstration" in an unpopulated area. But the momentum of a $2 billion project is hard to stop. The machine was already in motion.

Why This History Matters Today

Understanding the making of an atomic bomb isn't just a history lesson. It shows us how "Big Science" works. It set the template for the Apollo program and modern projects like the Large Hadron Collider. It proved that if you throw enough money, brilliant minds, and industrial capacity at a problem, you can basically break the laws of what seems possible.

It also serves as a warning about "technological imperatives"—the idea that once we can do something, we almost inevitably will do it, regardless of the consequences.

Actionable Insights for History and Tech Buffs

If you're looking to understand this period better, don't just watch movies. There are real-world sites and resources that give you a better sense of the scale:

- Visit the Manhattan Project National Historical Park: It's spread across Oak Ridge, Hanford, and Los Alamos. Seeing the size of the B Reactor in person changes your perspective on the industrial effort required.

- Read the Smyth Report: This was the official administrative history of the project released just days after the bombings. It’s surprisingly detailed about the technical hurdles they faced, though it leaves out the secret stuff.

- Study "The Making of the Atomic Bomb" by Richard Rhodes: Honestly, if you want the definitive word on this, this book is the Bible. It’s dense, but it covers the personalities and the physics with zero fluff.

- Examine the "Franck Report": Look this up to see the actual document where scientists tried to warn the government about the long-term dangers of a nuclear arms race before the first bomb was even dropped.

The reality of the bomb is far more complex than a mushroom cloud. It’s a story of silver magnets, leaky pipes, and thousands of people working in the dark to change the world forever.