You're staring at a chart. There’s a red line going up, a blue line starting from the bottom corner, and a gray horizontal line that just sits there. Somewhere in the middle, they cross. That little "X" marks the spot where you stop losing sleep and start making money. Honestly, a break even analysis graph is probably the most honest piece of paper in your entire business plan. It doesn't care about your "brand vision" or your "disruptive strategy." It only cares about the math.

If you’ve ever felt like you're working your tail off but the bank account isn't moving, you’ve hit the classic wall. You're selling, sure. But are you selling enough to cover the rent? Most people guess. Experts use the graph.

The Three Lines That Dictate Your Life

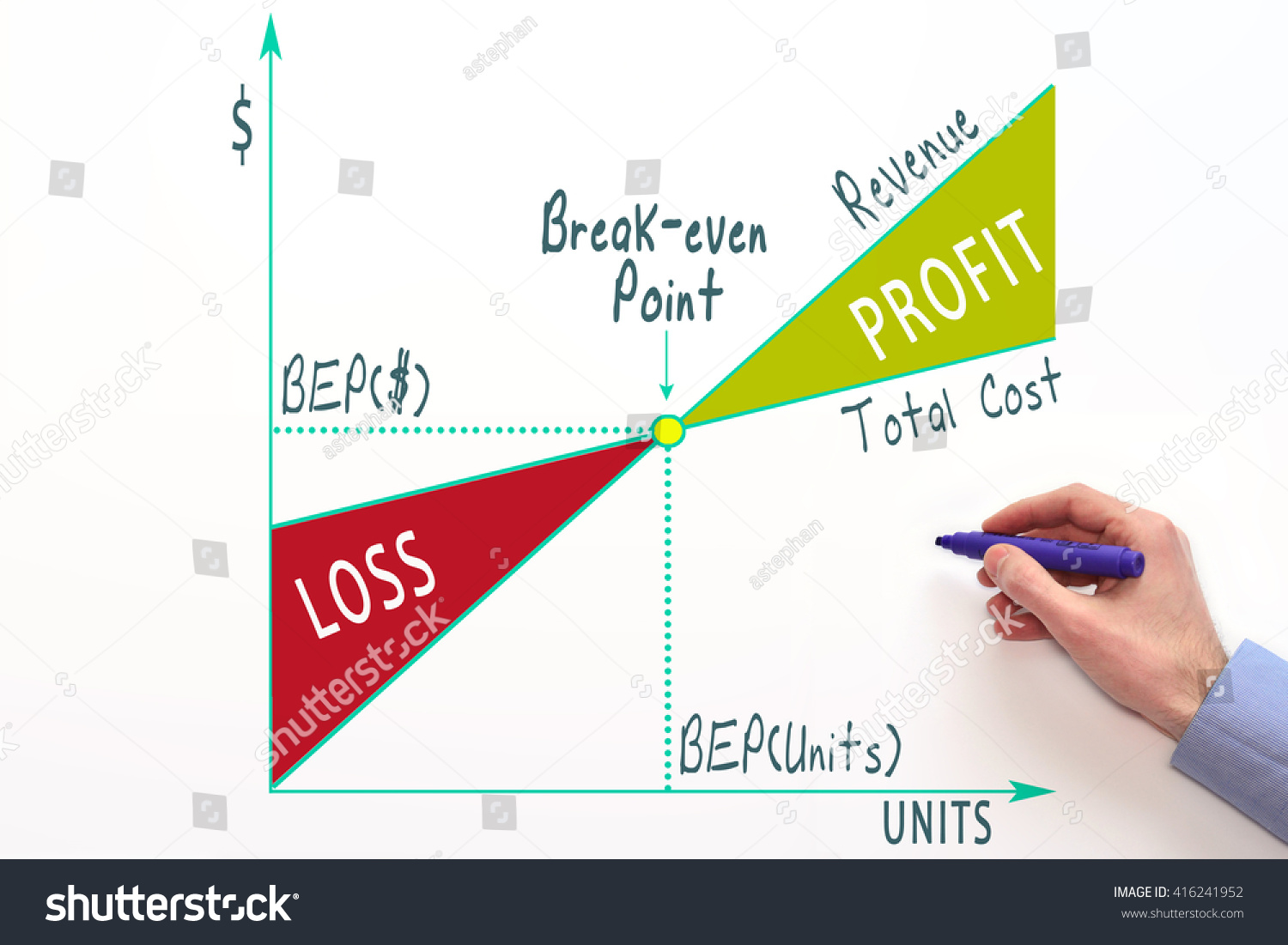

To get this right, you have to understand what you're looking at. It isn't just "lines on a page." It’s your rent, your inventory, and your paycheck.

First, there’s the Fixed Costs line. Think of this as the "Existence Tax." Whether you sell one widget or a million, this number stays flat. It’s a horizontal line. It includes things like your office lease, the insurance you pay every year, and the software subscriptions that hit your credit card every month. Even if you stay in bed all day and sell nothing, you still owe this money.

Then comes the Total Costs line. This one is tricky because it starts at the level of your fixed costs, not at zero. Why? Because the moment you open your doors, you're already in the hole for those fixed expenses. As you produce more, this line climbs. It adds Variable Costs—the raw materials, the shipping labels, the hourly labor—on top of the fixed stuff. If you're making hand-poured candles, the wax and the wicks are the variables. The more candles you make, the higher this line goes.

Finally, we have the Total Revenue line. This is the fun one. It starts at $0. If you sell nothing, you get nothing. But as you sell, this line shoots up. The steeper the angle, the more you're charging per unit.

The break even analysis graph happens when that revenue line finally crawls over the top of the total cost line. That intersection is the Break-Even Point (BEP). To the left of that point, you're hemorrhaging cash. To the right? That's the profit zone. That's where you actually start building wealth.

📖 Related: Top Class Action Lawsuits: What Most People Get Wrong

Why Your Intuition Is Probably Wrong

Most entrepreneurs are optimists. We have to be. But optimism is a terrible way to calculate a margin of safety. I’ve seen dozens of small business owners assume that if they have a 50% markup, they’re doing great.

They’re not.

A markup doesn't account for the "burn." If your fixed costs are $10,000 a month and you make $5 profit per item, you need to sell 2,000 items just to reach $0. Not to buy a car. Not to pay yourself. Just to keep the lights on. Seeing this on a break even analysis graph is often a bucket of cold water. It forces you to realize that your price might be too low, or your warehouse is too expensive.

The CVP Reality Check

In academic circles, this is often called Cost-Volume-Profit (CVP) analysis. According to studies by the Small Business Administration (SBA), a massive percentage of business failures stem from a lack of capital, but looking deeper, it’s often a failure to understand the relationship between volume and overhead. You can't "out-hustle" bad math. If your lines never cross, or if they cross so far to the right that you’d need a factory ten times your size to reach it, the business model is broken.

Making the Graph Work for You

Don't just draw this once and put it in a drawer. It's a living tool. You should be playing "what if" games with it.

What happens if your supplier raises the price of plastic by 15%? Your Total Cost line gets steeper. The "X" moves further to the right. Suddenly, you need to sell 500 more units a month just to break even.

What if you raise your prices? The Revenue line gets steeper. The "X" moves to the left. You can sell fewer items and still survive. This is why luxury brands love the break even analysis graph. They have massive margins, so their break-even point is often very low in terms of volume, even if their fixed costs (like a storefront on Fifth Avenue) are insane.

Margin of Safety: The Hidden Metric

There is a concept called the Margin of Safety that most people ignore. It’s the distance between your actual sales and the break-even point. If you’re selling 1,200 units and your break-even is 1,000, your margin of safety is 200 units. That’s your "oops" buffer. If a recession hits or a competitor opens across the street and your sales drop by 150 units, you’re still okay. If they drop by 250? You’re dead.

Common Mistakes People Make with the Visuals

One big mistake is forgetting that lines aren't always straight in the real world. In a perfect textbook break even analysis graph, everything is linear. In reality, you hit "step costs."

🔗 Read more: Why 2401 E Camelback Rd Phoenix AZ 85016 is the Real Heart of the Biltmore Financial District

Maybe your current kitchen can only handle 500 cakes. To sell the 501st cake, you have to rent a second kitchen. Suddenly, your fixed cost line jumps up like a staircase. If you don't account for these jumps, your graph will lie to you. You’ll think you’re in the profit zone when you’re actually about to hit a massive new expense that puts you back in the red.

Another thing? Ignoring the "Relevant Range." Your graph is only valid for a certain level of production. If you plan to sell 1,000,000 units, your variable costs might drop because you can buy materials in bulk. The line curves. The math changes.

Step-by-Step: How to Plot It

You don't need fancy software. Excel or a piece of graph paper works fine.

- Calculate Fixed Costs. Be ruthless. Don't forget the small stuff like your domain registration or the annual fee on your business credit card. Sum them up for a month. This is your horizontal starting point.

- Determine Variable Cost per Unit. How much does it cost in cold hard cash to produce one more item? Shipping, packaging, raw materials.

- Set Your Price. This is your revenue per unit.

- Pick Your Increments. On the bottom (X-axis), put "Units Sold." On the side (Y-axis), put "Dollars."

- Draw the Lines. * Start the Total Cost line at your Fixed Cost value on the Y-axis.

- Start the Revenue line at zero.

- Find the Intersection. That’s it.

The Nuance of Service Businesses

If you’re a consultant or a graphic designer, your break even analysis graph looks a bit different. Your "units" are hours. Your variable costs might be very low—maybe just the transaction fees on your invoices. Most of your costs are fixed (software, office, your own salary).

For a service business, the graph usually shows that once you hit a certain number of billable hours, almost everything else is pure profit. But there’s a ceiling: you only have 24 hours in a day. The graph helps you see exactly when you need to stop doing the work yourself and hire a junior associate to increase your capacity.

Actionable Next Steps

Stop guessing.

👉 See also: How much is one pound in dollars right now and why the rate keeps shifting

Take your profit and loss statement from the last three months. Separate every single expense into "Fixed" or "Variable." If you aren't sure, ask yourself: "If I closed for a month, would I still have to pay this?" If yes, it’s fixed.

Plot these numbers. If your break-even point is higher than your best sales month ever, you have three choices:

- Cut the fixed burn. Move to a cheaper office or cancel the "nice to have" tools.

- Lower the variable costs. Find a cheaper supplier or find a way to make the product faster.

- Raise the price. This is usually the scariest but most effective way to move that "X" to the left.

A break even analysis graph is a diagnostic tool. It tells you if your business is a lean machine or a sinking ship. Use it to decide if that new marketing campaign is actually worth the investment. If the campaign costs $5,000 (fixed cost), how much further does it push your break-even point? If you can't realistically hit that new number, don't run the ads. It's that simple.

The math doesn't have an ego. Neither should you.