You're standing in your kitchen, staring at a recipe from a European blog, and it says to preheat the oven to 200 degrees centigrade. If you live in the United States, your dial probably stops at 500 but starts around 200. Setting your oven to 200 degrees Fahrenheit when the recipe calls for Celsius is a recipe for raw dough and a very sad dinner. It's a common mix-up.

The short answer? 200 degrees centigrade is 392 degrees Fahrenheit.

But honestly, most people just round that up to 400°F and call it a day. Is that "correct"? Not technically. Does it work for a tray of roasted potatoes? Absolutely. Temperature conversion isn't just a math problem; it’s the difference between a golden-brown crust and a soggy mess.

Why Does 200 Degrees Centigrade to Fahrenheit Matter So Much?

Most of the world uses Celsius. It makes sense. Zero is freezing, and 100 is boiling. It’s clean. It’s logical. Then you have the Fahrenheit system, which feels like it was designed by someone throwing darts at a map. In Fahrenheit, water freezes at 32 and boils at 212.

When you convert 200 degrees centigrade to fahrenheit, you are dealing with a high-heat threshold. This isn't "room temperature" or "a slight fever." This is the "Maillard reaction" zone. Named after French chemist Louis-Camille Maillard, this is the chemical reaction between amino acids and reducing sugars that gives browned food its distinctive flavor. If you're off by fifty degrees because you guessed the conversion, your steak won't sear—it'll just gray.

The Raw Math (The "How" of it All)

If you want to be precise, you need the formula. It’s not as scary as high school algebra made it out to be.

To find Fahrenheit, you take your Celsius temperature, multiply it by 9, divide by 5, and then add 32.

$$F = (C \times \frac{9}{5}) + 32$$

Let's plug in the numbers. 200 times 9 is 1800. 1800 divided by 5 is 360. Add 32 to that, and you get exactly 392.

Some people prefer the decimal version: multiply by 1.8 and add 32. It’s the same result. $200 \times 1.8 = 360$. $360 + 32 = 392$.

Common Cooking Mistakes at 200°C

Kitchens are messy. Math is tidy. When these two worlds collide, things get burnt.

I’ve seen it a thousand times. A home cook sees "200" and forgets the unit. They set the oven to 200°F. An hour later, they’re wondering why their chicken is still translucent. On the flip side, if a recipe calls for 200°F (often used for slow-drying jerky or warming plates) and you set it to 200°C, you’ve basically created a localized furnace. You’ll have charcoal in twenty minutes.

Specific foods that thrive at 200°C:

💡 You might also like: Why roast potatoes by jamie oliver are still the gold standard for Sunday lunch

- Roast Potatoes: This is the "sweet spot" for crispiness.

- Puff Pastry: You need that high heat to turn the water in the butter into steam, which lifts the layers.

- Roasted Vegetables: Think broccoli or cauliflower with charred edges.

- Whole Chicken: It keeps the meat juicy while crisping the skin.

The Convection Factor

Here is where it gets tricky. If your oven has a fan (convection), 200°C is actually hotter than 200°C in a conventional oven. The moving air strips away the "cold air curtain" that surrounds food.

If a recipe says 200°C and you’re using a fan oven, you should actually drop the temperature to 180°C. That means instead of aiming for 392°F, you should be aiming for roughly 350°F to 360°F. If you don't adjust, you'll burn the outside before the inside is cooked. It’s a classic mistake that ruins Sunday roasts everywhere.

Beyond the Kitchen: Scientific Context

We talk about 200°C mostly in terms of baking, but it’s a significant number in other fields too. In soldering, 200°C is around the melting point for many lead-based solders, though lead-free versions usually require a bit more heat. If you're a hobbyist fixing a circuit board, knowing that 200°C is almost 400°F gives you a sense of the "burn risk" involved.

In the world of hair care, 200°C is often the maximum recommended temperature for flat irons. Any hotter and you’re literally melting the keratin in your hair strands. If your straightener is set to 400°F, you are right on that "danger zone" edge.

Why do we even have two systems?

It’s a historical hangover. Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit came up with his scale in 1724. He used brine and human body temperature as his reference points. Later, Anders Celsius created his scale in 1742, basing it on the properties of water.

The United States stayed with Fahrenheit mostly because of the massive cost and confusion associated with switching the entire country's infrastructure to metric. Britain actually uses a weird mix. They’ll tell you the weather in Celsius but talk about oven temps in "Gas Mark" or Celsius, yet still use miles for road signs. It’s chaotic.

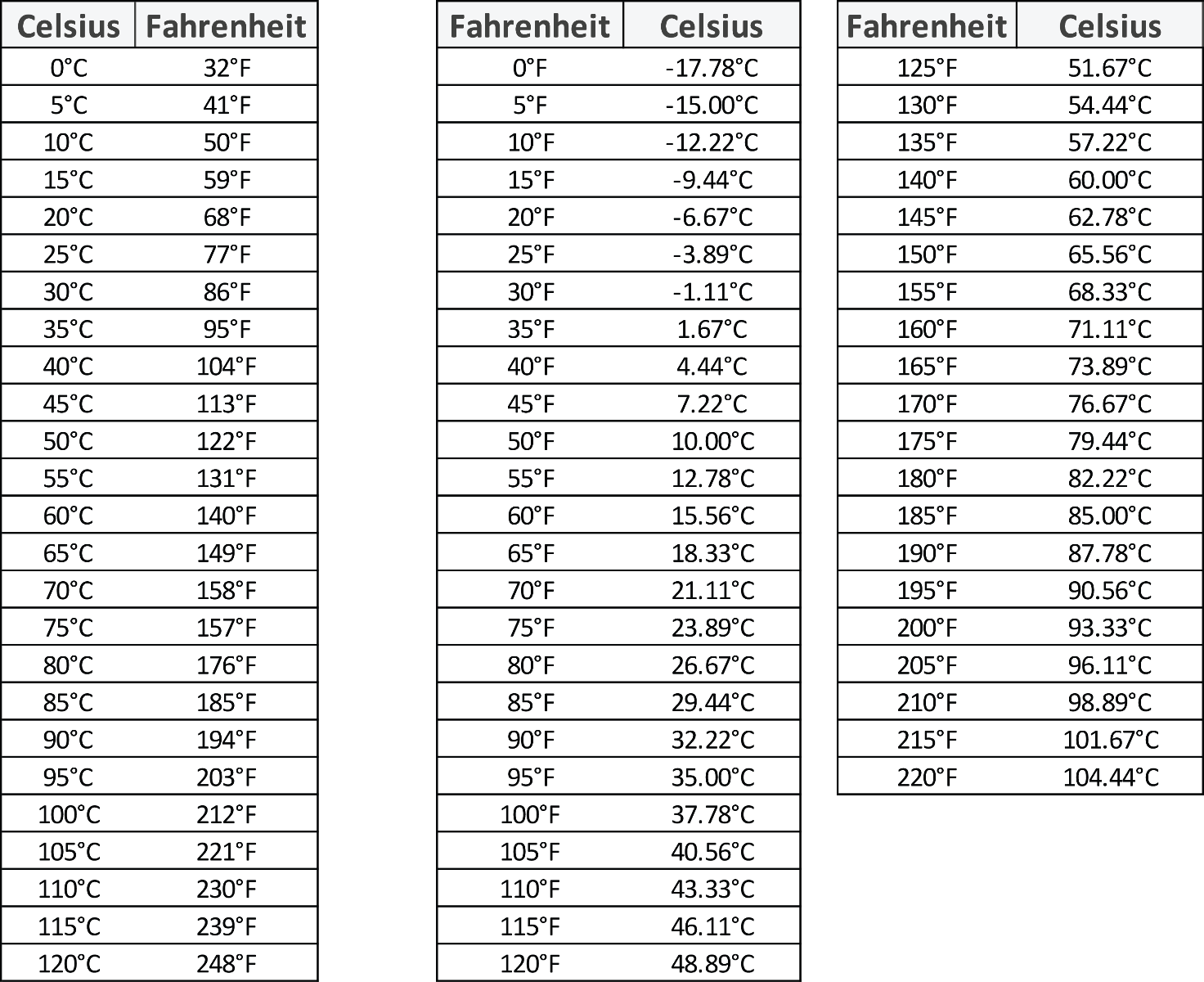

Quick Reference Conversion Cheat Sheet

You don't always need the exact 392. Sometimes "close enough" is what saves the meal.

If you see 150°C, think 300°F. It’s actually 302, but who’s counting?

If you see 180°C, that’s your standard 350°F (actually 356).

If you see 200°C, hit 400°F on your dial (actually 392).

If you see 220°C, go for 425°F or 450°F (actually 428).

Notice how the gap grows? It’s not a 1:1 ratio. Because the Fahrenheit "degree" is smaller than a Celsius "degree," the numbers pull apart the higher you go. For every 5 degrees Celsius you move, you move 9 degrees Fahrenheit.

What about Gas Marks?

If you’re using an old-school British oven, 200°C is Gas Mark 6. If you find a recipe that just says "Hot Oven," they usually mean 200°C to 220°C. "Moderate" is 180°C. "Cool" is 150°C.

The Precision Trap

Honest truth? Most home ovens are terribly calibrated.

You might set your oven to 392°F (or 400°F) to match that 200°C requirement, but your oven might actually be hovering at 375°F or spiking to 425°F. Ovens cycle heat on and off. They have hot spots. This is why a $15 oven thermometer is more important than knowing the exact math.

I once spent an afternoon testing three different ovens in the same apartment building. None of them were accurate. One was off by 25 degrees. If you’re baking something delicate like Macarons, that 25-degree difference is a death sentence for your cookies.

Practical Steps for Conversion Success

- Get a physical thermometer. Stop trusting the digital display on your stove. It lies. Place a secondary thermometer on the middle rack.

- Use the "Rule of 2" for quick math. To get a rough Fahrenheit number from Celsius, double the Celsius and add 30. $200 \times 2 = 400$. $400 + 30 = 430$. Okay, it’s not perfect (it’s high), but it’s a quick way to see if you’re in the right ballpark when you’re at the grocery store without a calculator.

- Write it down. If you have a favorite international cookbook, take a Sharpie and write the Fahrenheit conversions next to the Celsius temperatures in the margins. Your future self will thank you.

- Adjust for Altitude. If you are living in the mountains, water boils at a lower temperature. While this doesn't change the conversion of 200°C to 392°F, it does change how food cooks at that temperature. You may need to increase your liquid or slightly decrease your baking time.

Understanding the shift from 200 degrees centigrade to fahrenheit is basically a rite of passage for anyone who loves to cook or build things. It’s one of those bits of "useless" knowledge that suddenly becomes very useful when you’re hungry and the recipe is in a different language.

Stick to the 392 rule, but don't be afraid to round to 400 if you're just roasting some carrots. The kitchen is a lab, but it's also a place to trust your gut. If the food looks like it's burning, it doesn't matter what the thermometer says. Turn it down.

To ensure your oven is actually hitting these marks, buy an independent oven thermometer today and place it in the center of your oven rack. Check it against your dial settings to find your oven's "true" offset. For any future conversions, bookmark a reliable ratio chart or memorize the $1.8 + 32$ formula to handle odd numbers like 175°C or 190°C with ease.