Let's be real for a second. Most people trying to figure out how to draw rib cage structures end up with something that looks like a literal cage from a medieval dungeon or, worse, a lumpy potato. It’s frustrating. You’ve got the head looking decent, the limbs are okay, but then the torso just... collapses. It’s either too flat, too wide, or it doesn't seem to connect to the hips in any way that makes sense for a living human being.

The rib cage is the "chassis" of the human figure. If the chassis is bent, the car won't drive. In drawing, if your rib cage is off, your entire pose will feel "broken" no matter how much muscle detail you render on top.

Most beginners make the mistake of drawing it as a flat circle or a simple rectangle. But the rib cage—the thoracic cage, if we’re being fancy—is a complex, egg-shaped volume that tilts, rotates, and compresses. Understanding this isn't just about anatomy; it's about movement. If you can't visualize that volume in 3D space, you're going to struggle with every single pose that isn't a straight-on mugshot.

The Egg Shape Myth and Reality

You’ve probably seen the "egg" method. It’s a classic. Every art teacher from Bridgman to Loomis mentions it. Honestly, it's a great starting point, but it's also a bit of a trap. If you just draw an egg, you forget about the most important part: the sternum and the thoracic arch.

The rib cage isn't a perfect oval. It’s wider at the bottom than the top, and it has a very distinct "cutout" at the front where the ribs meet the abdomen. This is called the thoracic arch, or the inverted "V." When you're learning how to draw rib cage forms, this V-shape is your best friend. It tells you exactly where the torso is pointing.

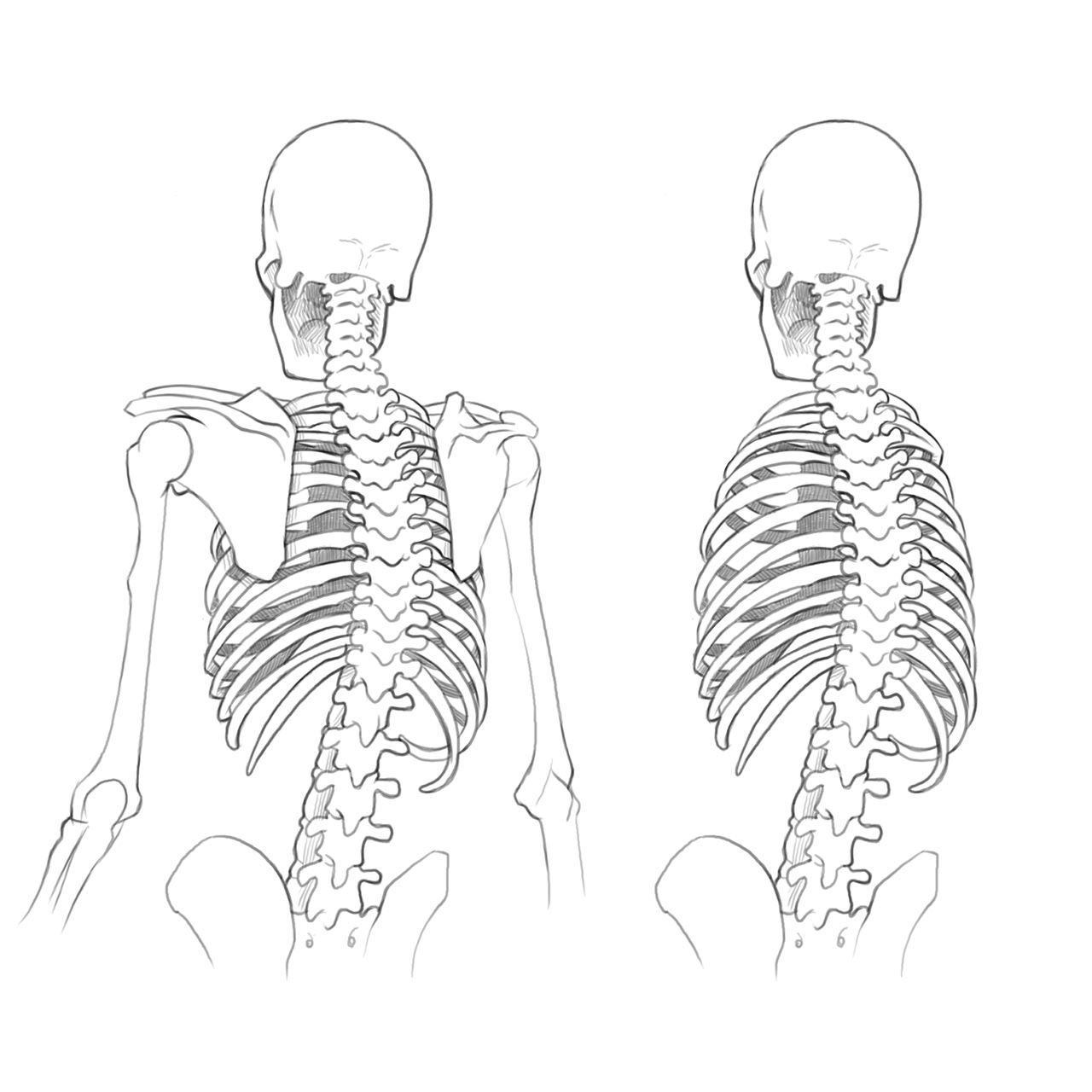

Think about the spine for a moment. It doesn't just sit on the back; it's the literal anchor. The ribs grow out from the vertebrae, curve around, and most of them tuck into the sternum at the front. When you draw that egg shape, you need to imagine a line wrapping around it to represent the tilt of the ribs. Ribs don't go straight across like stripes on a shirt. They angle downward. If you draw them horizontally, your character will look like they’re wearing a barrel, not like they have a skeleton.

Visualizing the Volume in 3D

I once watched a demo by the legendary Glenn Vilppu, and he emphasized one thing above all else: volume. He didn't care about the individual ribs. He cared about the box.

Wait, a box? I thought we said it was an egg?

Well, it’s both. This is where people get tripped up. To get the perspective right, it helps to imagine the rib cage inside a box. This helps you find the "corners." Even though the ribs are rounded, there are clear front, side, and back planes.

- The Front Plane: This is defined by the sternum and the flat-ish area of the chest.

- The Side Planes: These are where the serratus anterior muscles (those "finger-like" muscles on the side) live.

- The Back Plane: This is dominated by the shoulder blades (scapula) and the long muscles of the back.

If you can draw a box in perspective, you can draw a rib cage. You just "round off" the corners of that box until it starts looking human. This prevents that "paper-doll" effect where the character looks like they’re made of cardboard. It gives them weight. It gives them presence.

The Connection Point: The Seventh Cervical Vertebra

If you're wondering where to start, look for the "bump." Reach behind your neck. Feel that bone sticking out at the base? That’s C7—the seventh cervical vertebra. In the world of figure drawing, this is a landmark.

Everything starts here. The rib cage hangs off the spine starting just below this point. When you're figuring out how to draw rib cage angles, find the C7 and the pit of the neck (the suprasternal notch). If you connect these two points through the body, you have the tilt of the "top" of the cage.

Most people draw the neck coming straight out of the top of the ribs. It doesn't. The neck is angled forward, and the rib cage is angled slightly backward to balance the weight. It's a game of counterweights. If the head goes forward, the rib cage usually tilts back. If you miss this, your character will look like they’re about to fall over.

Common Pitfalls: The Floating Ribs and the Scapula

We have twelve pairs of ribs. Do you need to draw all of them? Heavens, no. Unless you’re doing a medical illustration for a textbook, drawing every rib is the fastest way to ruin a drawing. It makes the figure look "scrubby" and over-detailed.

✨ Don't miss: How to Find and Use Boylan Funeral Home Obituaries Without the Usual Stress

Instead, focus on the "rhythm."

The bottom edge of the rib cage is what matters most for the silhouette. This is where the "obliques" (the side abs) attach. If you get the bottom of the ribs wrong, the waist will look weird. Some people draw the waist too high because they think the ribs end right under the chest. In reality, the ribs go down surprisingly far, often ending just a few inches above the belly button.

Then there's the scapula—the shoulder blades. These things are weird. They aren't actually part of the rib cage; they "float" on top of it, held in place by muscle. When you move your arms, the rib cage stays relatively still, but the scapulae slide all over the place. A common mistake is "locking" the shoulders to the rib cage. Don't do that. Treat the rib cage as the solid base and the shoulders as a separate harness that sits on top.

How to Draw Rib Cage Landmarks for Better Accuracy

If you want your drawings to look professional, you need to hit the "landmarks." These are the bony bits that are visible even on people who aren't bodybuilders.

- The Pit of the Neck: That little hollow between the collarbones.

- The Sternum: The "breastbone." It’s a flat, tie-shaped bone in the center.

- The Thoracic Arch: The upside-down V at the bottom of the sternum.

- The 10th Rib: Usually the lowest point of the rib cage visible from the front.

- The Spine: Specifically the curve of the thoracic vertebrae.

When you're sketching, just ghost these in. You don't need hard lines. Just a suggestion of where they are will guide your shading and your muscle placement. It's basically a roadmap.

Perspective and the "Pinch and Stretch"

This is where the magic happens. When a person leans to one side, the rib cage doesn't change shape, but the space between the rib cage and the pelvis does.

On one side, the flesh "pinches" (folds), and on the other side, it "stretches."

But here’s the kicker: the rib cage can also twist independently of the hips. This is called "contrapposto" or just general torso rotation. When the rib cage twists, the sternum will point in a different direction than the belly button. If you’re struggling with how to draw rib cage rotations, try drawing the rib cage and the pelvis as two separate blocks connected by a flexible "bean" shape.

This "bean" concept, popularized by artists like Preston Blair and later refined by modern instructors like Proko, is essential. The rib cage is the top half of the bean. It’s the rigid part. The "squishy" part is the abdomen. If you make the ribs squishy, the drawing dies. Keep the cage solid.

Shading the Volume

Once you've got the shape, you have to make it look 3D. Since the rib cage is basically a rounded box or a modified egg, the light will hit it in a specific way.

Usually, there's a "core shadow" that runs down the side of the ribs. This follows the change in plane from the front to the side. Because the ribs are slightly textured, this shadow won't be a perfectly smooth gradient; it’ll have a bit of a "stair-step" feel to it as it passes over the individual ribs.

But don't overdo it! A light touch is better. Just suggest the "rhythm" of the ribs near the serratus muscles. Think of it like drawing a fan. The ribs radiate out from the back and wrap around.

The Difference Between Sexes

It's a common misconception that men and women have a different number of ribs. They don't. (That's an old myth from a certain famous book, but biology says otherwise).

However, the proportions differ.

Generally speaking, a male rib cage is broader and more "barrel-chested." The thoracic arch (that V-shape) tends to be slightly more acute. In females, the rib cage is often narrower and more cylindrical. The shoulders are usually narrower relative to the hips, which changes how the rib cage looks in the overall silhouette. When you're learning how to draw rib cage variations, keep these subtle proportional shifts in mind. It's not about changing the "bones" so much as changing the "scale."

Let’s Talk About Breathing

Wait, breathing? In a drawing?

Yes. The rib cage is dynamic. When someone takes a deep breath, the ribs lift and expand. The thoracic arch widens. The sternum moves forward and up. If you're drawing a character who is out of breath or shouting, you have to change the shape of the cage.

If you draw a static, "neutral" rib cage for a high-action pose, it’ll look like the character is a statue. For an inhale, tilt the rib cage back further and "inflate" the chest. For an exhale, let the ribs drop and the arch narrow. These tiny adjustments make the difference between a "good" drawing and one that feels alive.

Actionable Steps to Master the Rib Cage

Look, reading about it is one thing. Doing it is another. If you actually want to get better at how to draw rib cage structures, you need to put the pencil to the paper.

- Do 50 "Bean" Sketches: Forget the details. Just draw the relationship between the rib cage and the pelvis. Twist them, tilt them, and lean them. Do this until you can feel the volume.

- Trace Over Photos: Take a magazine or a printed photo of a model. Use a red marker to find the sternum, the thoracic arch, and the C7 vertebra. Draw the "box" around their torso. This trains your brain to see through the skin to the skeleton.

- Draw the "Negative Space": Sometimes it’s easier to see the rib cage by looking at the air around it. Look at the angle between the arm and the side of the ribs.

- Simplify to a Cylinder: If the egg is too hard, start with a cylinder. It’s the easiest way to understand how light wraps around the torso. Once you can shade a cylinder, you can shade a rib cage.

- Check Your Centerline: Always, always draw a line down the middle of the sternum. This "medial line" is your North Star. If it’s off-center, the whole drawing will look warped.

Stop worrying about making it look "pretty" for now. Focus on making it look solid. A "homely" drawing that has correct volume and weight is always better than a "beautiful" drawing that is structurally broken. You can always add pretty rendering later, but you can't fix a broken skeleton with fancy shading.

The rib cage is the foundation. Get the foundation right, and the rest of the figure will almost draw itself. Well, okay, maybe not draw itself, but it certainly gets a whole lot easier.

Keep your pencils sharp and your observations sharper. The next time you're out in public, don't be a creep, but try to "see" the thoracic arch on the people around you. Notice how it moves when they sit, stand, or reach for a coffee. That's the best art school there is.