Most people mess up desert drawings because they think the desert is empty. They see a photo of the Sahara or the Mojave and see "nothing," so they draw nothing. But the desert is crowded. It is crowded with heat haze, grit, ancient geology, and light that hits like a physical weight. If you want to know how to draw the desert, you have to stop drawing sand and start drawing the atmosphere.

Think about the last time you saw a really bad drawing of a dune. It probably looked like a series of triangles or waves on a blue background. It felt sterile. Real deserts are messy. They are chaotic. Even the most pristine sand dunes are covered in ripples caused by wind fluid dynamics—a concept often studied by geomorphologists like those at the United States Geological Survey (USGS). If you miss those micro-textures, your drawing will always look like a cartoon.

Drawing a desert isn't just about the dunes. It’s about the silence. It’s about the way the sun obliterates detail in the highlights and hides secrets in the purple shadows.

Why Your Desert Drawings Look Flat

The biggest enemy of a desert landscape is a lack of atmospheric perspective. In a forest, you have trees to show scale. In a city, you have buildings. In the desert, you might have a single Joshua tree or a lonely cactus, but mostly, you have vast distances.

👉 See also: November 23rd Horoscope: The Truth About Being a First-Decan Archer

When you’re learning how to draw the desert, you have to master the "fading" effect. Objects further away aren't just smaller; they are lighter and bluer. This is Rayleigh scattering. Even in the dry air of the Sonoran, there is dust. That dust catches the light.

The Horizon Line is a Liar

I’ve seen so many beginners draw a straight line across the paper and call it the horizon. Don't do that. The desert floor is rarely flat. It’s a series of alluvial fans, dry washes (arroyos), and volcanic outcrops.

Instead of a flat line, try layering your horizon.

- Foreground: High contrast, sharp edges, visible pebbles, and cracks in the playa.

- Middle ground: Softening textures, larger landforms like mesas, and the start of heat distortion.

- Background: Pale silhouettes. These should almost blend into the sky.

If you make your distant mountains too dark, you’ve just killed the sense of scale. You’ve shrunk the world.

Mastering the Texture of Sand and Rock

Sand is a nightmare to draw if you try to draw every grain. Please, don't try to draw every grain. It won't work. Instead, focus on the "comb" of the wind.

When wind moves over a dune, it creates saltation—the process where grains bounce along the surface. This creates those iconic ripples. In your drawing, these ripples should follow the contour of the dune. Think of it like wrapping a striped blanket over a pillow. The lines must curve to show the volume underneath. If the lines are straight, the dune looks flat.

Wait, what about the rocks? Deserts like the Black Rock Desert in Nevada or the Badlands have specific rock formations. You aren't just drawing "rocks." You are drawing erosion. Water is the primary architect of the desert, even if it only shows up once a year. Look at the work of Ansel Adams or the paintings of Georgia O’Keeffe. They understood that desert rock has "muscles." It has deep fissures and weathered faces.

Use cross-hatching to show the grit. If you’re using charcoal, use a kneaded eraser to "pull" the light out of the dark masses. This mimics the way sunlight reflects off quartz and feldspar.

The Secret of High-Key Lighting

The desert is bright. Honestly, it’s blinding. This is why many successful desert artists use a "high-key" palette. This means most of the values in your drawing should be on the lighter end of the scale.

When figuring out how to draw the desert, many people make the mistake of using too much black. In a midday desert scene, shadows are rarely pitch black. They are often filled with reflected light from the sand. Look at the "blue" shadows in the Mojave. Because the sky is so vast and clear, it acts as a secondary light source, filling the shadows with a cool, ambient glow.

- Map your light source. Decide exactly where the sun is.

- Avoid pure white. Save the actual white of the paper for the absolute brightest highlights—like the edge of a dune or a glint off a rock.

- Shadow temperature. If your light is warm (yellow/orange), your shadows should be cool (purple/blue).

Dealing with the Sky

The sky in a desert drawing shouldn't be a solid block of blue. It’s a gradient. Near the horizon, the sky is often paler, almost white or yellow-tinted due to dust. As you look "up" (toward the top of your paper), the blue should deepen. This creates an "inverted bowl" effect that makes the viewer feel small.

Adding Life Without Cliché

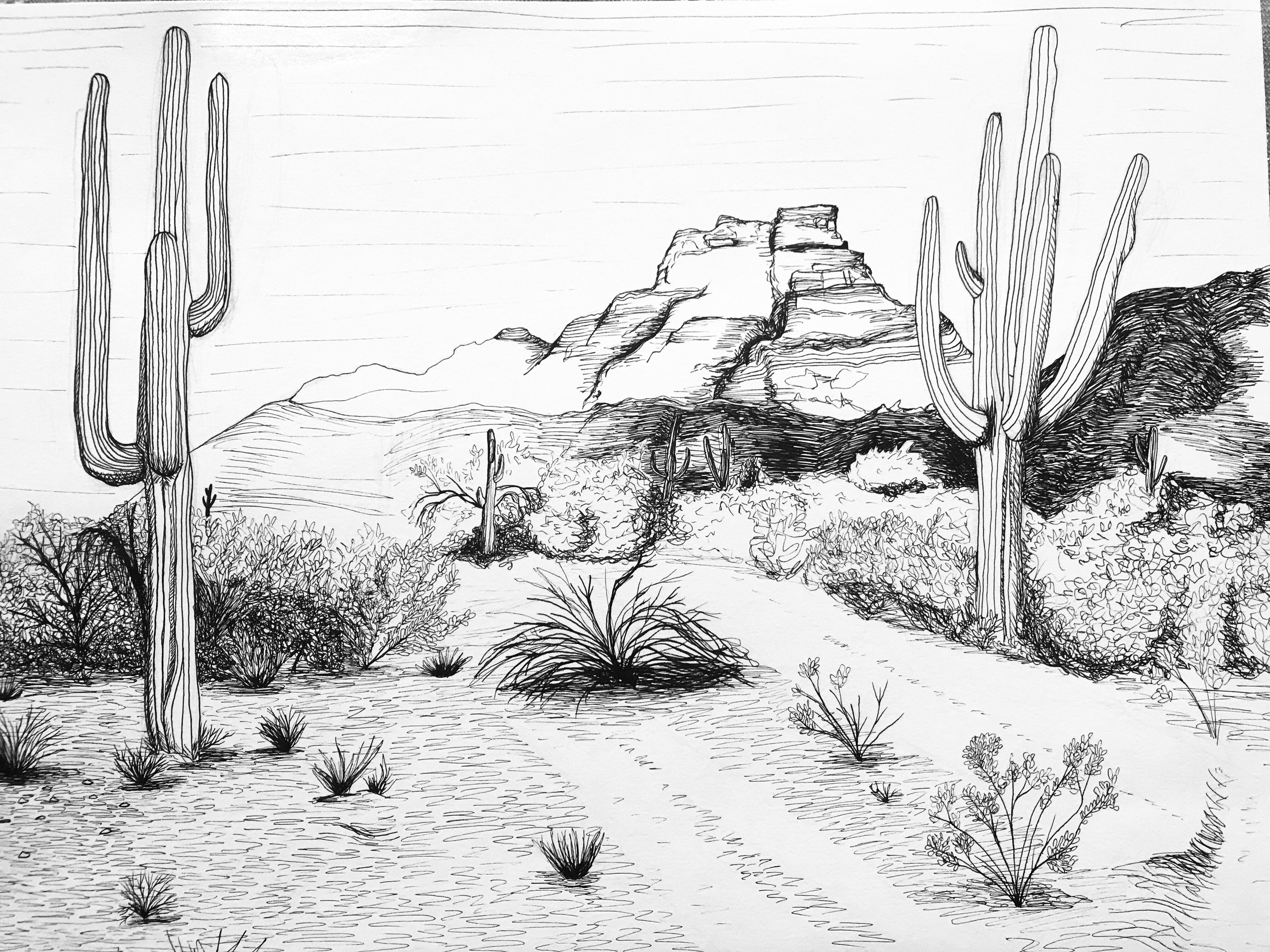

Every amateur adds a cow skull or a saguaro. There’s nothing wrong with that, but it’s a bit overdone. If you want your desert to feel real, look at the biology.

Draw the creosote bushes. They aren't pretty; they look like messy, spindly clumps of sticks with tiny green leaves. But they are everywhere in the American Southwest. Draw the "desert pavement"—that layer of tightly packed pebbles that looks like a mosaic.

If you do draw a cactus, remember the "ribs." A saguaro isn't a smooth pipe. It has vertical pleats that allow it to expand when it soaks up water. These ribs create hundreds of tiny vertical shadows. Drawing those shadows is what makes the cactus look three-dimensional.

Technical Nuance: The Heat Haze

One thing almost everyone misses when learning how to draw the desert is the shimmer. Heat haze, or "mirage," happens because hot air is less dense than cool air, causing light to refract.

In your drawing, you can simulate this by slightly blurring the base of distant mountains. Don't make the lines sharp. If you’re using pencils, use a blending stump (tortillon) to smudge the very bottom of the distant landforms. It creates that "floating" look you see on a 110-degree day in Death Valley. It makes the viewer feel the heat.

Why Perspective Matters Here

Linear perspective is easy when you have a road. But what if you don't? You have to use "size diminution" of random objects. A clump of bunchgrass in the foreground might be an inch tall on your paper. A similar clump fifty yards away should be a mere dot.

Consistency is key. If your foreground pebbles are the same size as your middle-ground rocks, the eye gets confused. It feels like a miniature model rather than a vast landscape.

Tools for the Job

You don't need fancy gear, but some things help.

- Graphite Pencils: A 2H for those pale, distant mountains and a 4B for the deep fissures in foreground rocks.

- Toned Paper: This is a game-changer. Use tan or grey paper. Since the desert is mid-toned anyway, you can use a white charcoal pencil for the highlights and a dark pencil for the shadows. It’s much faster than working on white paper.

- Soft Pastels: If you’re working in color, ochres, sienna, and ultramarine are your best friends.

Actionable Steps to Improve Your Desert Art

Start small. Don't try to draw the entire Grand Canyon on day one. You'll get overwhelmed and quit.

First, practice drawing a single rock. Focus on the planes. A rock is just a series of flat surfaces meeting at angles. If you can draw a convincing rock, you can draw a mountain, because a mountain is just a very big rock.

Second, master the "S" curve. Most dunes follow a sweeping "S" shape. Practice drawing these curves with a light hand. The "crest" of the dune is where the most drama happens—it’s the sharp line where the windward side meets the leeward side. One side will be in bright light, the other in deep shadow.

Third, go outside. If you live near a desert, go there at "Golden Hour"—the hour before sunset. Watch how the shadows stretch. They become incredibly long, sometimes hundreds of feet. In a drawing, these long shadows act as "leading lines" that pull the viewer’s eye into the composition.

Fourth, study the experts. Look at the photography of Edward Weston. His photos of the Oceano Dunes are masterclasses in form and shadow. Even though they are sand, they look like human bodies—curvy, muscular, and alive.

Finally, embrace the "empty" space. In the desert, what you don't draw is just as important as what you do. Negative space (the sky, the flat playas) gives the viewer room to breathe. It emphasizes the isolation.

Stop thinking of the desert as a wasteland. Treat it like a portrait. Every crack in the earth is a wrinkle; every dune is a limb. When you start seeing the desert as a living thing, your drawings will stop looking like sandboxes and start looking like art. Focus on the contrast between the sharp, jagged edges of the rocks and the soft, flowing curves of the sand. That tension is where the beauty lives. Keep your pencil moving, keep your values light, and don't be afraid to leave a lot of the page blank. That's the desert way.