So, you’ve finally mastered that sourdough or that spicy Thai basil chicken that actually tastes like the restaurant version. Awesome. But then the reality check hits when you realize you have zero clue how many calories are in it or if the sodium levels are through the roof. Honestly, trying to figure out how to find nutrition facts for a recipe usually feels like a high school chemistry project you didn't study for. It's tedious. You start looking at a bag of flour, then a tablespoon of oil, then you’re trying to calculate the weight of a "medium" onion, and suddenly you just want to order pizza and forget the whole thing.

Calculators exist, sure, but they aren't all created equal. Some are basically just guessing. Others are so detailed they ask for the specific brand of salt you used, which is overkill for most of us. If you're tracking macros for the gym or managing a condition like diabetes, "close enough" doesn't always cut it. You need a method that actually reflects the food on your plate, not some generic version of it found in a database from 1998.

The Problem With Generic Database Searches

Most people start by Googling "calories in homemade lasagna." Big mistake. Huge.

🔗 Read more: Does Coconut Oil Have Sunscreen? Why This Natural Trend Is Actually Dangerous

When you do that, Google gives you a snippet from a random blog or a generic entry from a fitness app. But your lasagna isn't their lasagna. Did you use whole milk ricotta or the skim stuff? Was your ground beef 80/20 or 95% lean? Those tiny shifts can swing the calorie count by 200 per serving without you even noticing. If you really want to know how to find nutrition facts for a recipe that you actually cooked, you have to treat the recipe as a sum of its parts.

Nutrition is math, unfortunately. But it’s math that software can do for you if you feed it the right data.

The USDA FoodData Central is the gold standard here. It’s what most of those fancy apps pull from anyway. If you go straight to the source, you get the most accurate, lab-tested data available. The problem? It’s a bit clunky to use for a casual Tuesday night dinner. That's why "recipe analyzers" became a thing. They act as the middleman between the USDA’s massive spreadsheet and your kitchen counter.

Why Precision Matters More Than You Think

A single tablespoon of olive oil is 120 calories. If you "glug" it into the pan instead of measuring, you might be adding three tablespoons. That’s 360 calories before you’ve even added the protein.

If you're doing this for weight loss or heart health, these "invisible" calories are usually why the scale doesn't move even when you're "eating healthy." Using a digital scale is the only way to be 100% sure. Volume measurements—cups and spoons—are notoriously unreliable for solids. A cup of flour can weigh anywhere from 120 to 160 grams depending on how tightly you pack it. That’s a 150-calorie variance just in the breading of a chicken breast. Use grams. It's easier, fewer dishes to wash, and way more accurate.

How to Find Nutrition Facts for a Recipe Using Online Tools

You've probably heard of MyFitnessPal or Lose It!. They have "Recipe Importers." You paste a URL, and it tries to guess what the ingredients are. It’s... okay. It’s not great. It often misses things or picks the wrong version of an ingredient.

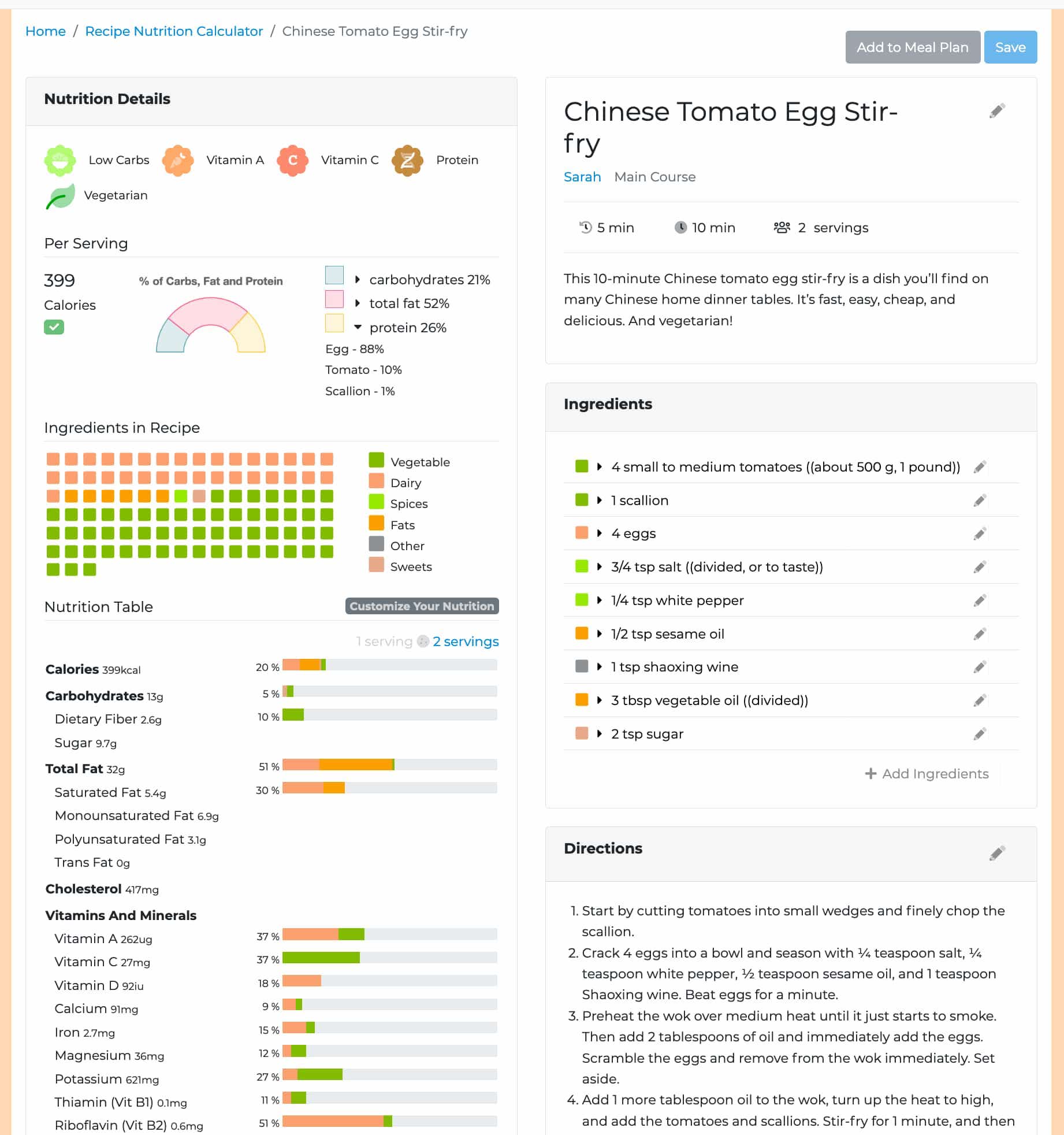

A better way? Verywell Fit’s Recipe Analyzer or the tool on Cronometer.

Cronometer is widely loved by dietitians because they verify their data. They don't just let any random user upload "My Mom's Magic Casserole" with zero data and call it a day. When you're looking for how to find nutrition facts for a recipe, you want a tool that forces you to be specific.

- List every single raw ingredient. Cooking changes weight (water evaporates), but the calories mostly stay the same (unless you're draining fat).

- Account for the "yield." This is where people mess up. If the pot of soup weighs 2000 grams when finished, and you eat 500 grams, you ate 25% of the total nutrients.

- Don't forget the cooking fats. If it goes in the pan, it goes in the log. Even the butter you used to grease the baking dish.

The Secret "Weight-Out" Method for Accuracy

This is what the pros do. It sounds obsessive, but it’s actually the simplest way to get a per-gram breakdown.

First, weigh your empty cooking pot or pan. Write that number down on a sticky note. Then, cook your meal. Once it’s done, weigh the full pot. Subtract the weight of the empty pot. Now you have the total weight of the finished food.

Let's say your total recipe ingredients (raw) come out to 4,000 calories. Your finished dish weighs 1,000 grams. Now you know that every single gram of that food is 4 calories. If you scoop out 250 grams for lunch, you're eating exactly 1,000 calories. No guessing. No "is this a cup or a cup and a half?" It’s just physics.

Dealing With "Hidden" Changes During Cooking

Cooking is a chemical reaction. Alcohol burns off (mostly, but not all of it—a common myth is that it all vanishes instantly; it actually takes quite a while). Water evaporates, which concentrates the nutrients. This is why a "cup" of cooked spinach has vastly different nutrition than a "cup" of raw spinach.

Always log your ingredients in their raw state unless the database specifically has an entry for "cooked, braised" or "cooked, roasted." For meat, the USDA has entries for "raw" and "cooked, roasted, fat trimmed." Use the one that matches how you weighed it. If you weigh your steak after it hits the grill, use the "cooked" entry. If you weigh it straight out of the butcher paper, use "raw."

Reliability of Public Databases

Not all data is good data.

If you see an entry that says "1 bowl of soup - 100 calories," ignore it. It's useless. Who's bowl? What soup? You want entries that list "per 100g" or "per ounce."

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) often points researchers toward the FoodData Central (FDC) because it separates "Foundation Foods"—which are heavily tested—from "Branded Foods" which are just data pulled from labels. Label data is allowed to have a 20% margin of error according to FDA regulations. That’s a lot! If a label says 100 calories, it could legally be 120. When you're building a recipe, that margin of error compounds. Stick to the foundation food data whenever possible for staples like eggs, rice, and vegetables.

What About Apps?

Apps are basically skins for these databases.

- Cronometer: Best for accuracy and micro-nutrients (vitamins/minerals).

- MyFitnessPal: Best for finding specific brand-name items but full of user-generated errors.

- MacroFactor: Excellent for people who want the app to adjust their targets based on weight trends, and it has a very fast manual entry system.

Honestly, if you're trying to figure out how to find nutrition facts for a recipe for the first time, start with a simple web-based analyzer. You don't need a subscription to get a basic breakdown of a pan of brownies.

Don't Overthink the Small Stuff

You don't need to track black pepper. You don't need to track cinnamon. Spices have calories, sure, but unless you're eating a quarter-cup of cumin, it's rounding error territory. Stressing over the 2 calories in your garlic powder is a fast track to burnout. Focus on the big movers: fats, proteins, and starches.

Also, realize that fiber is a wildcard. Some apps subtract fiber from total carbs to give you "net carbs." Others don't. Depending on your health goals, this distinction is huge. If you're keto, you care deeply. If you're just trying to eat more whole foods, the total carb count is probably fine.

Practical Steps to Get Your First Recipe Analyzed

Start with something you make often. There's no point in analyzing a 12-course Thanksgiving dinner you only eat once a year. Pick your "workday lunch" or that "lazy Sunday pasta."

- Grab a digital scale. Stop using measuring cups for anything that isn't liquid.

- Write down the raw weights of everything as you prep.

- Use a "Recipe Importer" like the one on Verywell Fit or Cronometer.

- Compare the results to a similar store-bought version. If your homemade version says it has 1,000 fewer calories than a Lean Cuisine, you probably missed an ingredient (usually the oil or butter).

- Adjust for servings. Decide if you’re cutting that lasagna into 6 pieces or 8. Be realistic. If you know you're going to eat a "double serving," just account for it.

The first time you do this, it will take 15 minutes. The tenth time, it’ll take two. Eventually, you’ll start to see patterns. You'll realize that the "light drizzle" of oil you've been using is actually 300 calories, and you might decide to swap it for a non-stick spray. That’s the real power of knowing how to find nutrition facts for a recipe—it changes how you cook, not just how you track.

Knowing the data gives you the agency to make swaps. Maybe you replace half the ground beef with lentils. Maybe you realize that the heavy cream in your coffee is actually more caloric than the breakfast itself. Knowledge is power, or at least, it's a way to stop wondering why your "healthy" recipes aren't yielding the results you expected.

Get your scale out. Open a tab with a trusted analyzer. Start with your next meal. Don't worry about being perfect; just aim to be better than a blind guess. Once you have the data for your five most-cooked meals, you've already done 80% of the work. You can just save those recipes in your app of choice and never have to calculate them again. It’s a one-time investment for a long-term understanding of what you’re putting in your body.