We’ve all been there. You grab a stray sheet of printer paper, fold it into a generic point, and chuck it with high hopes, only to watch it nose-dive into the carpet three feet away. It’s frustrating. Honestly, most people think the secret is just "folding harder," but that’s not really it. If you want to know how to make a great paper plane, you have to stop thinking about it as a toy and start thinking about it like a glider. It’s about physics, center of gravity, and—this is the part everyone ignores—the quality of your paper.

Paper flight isn't magic. It's fluid dynamics.

💡 You might also like: Why a Sentence With Segregation Still Shapes Modern Neighborhoods

When you throw a plane, you're dealing with four forces: lift, weight, thrust, and drag. Most DIY planes fail because they have too much drag and not enough lift, or their center of gravity is so far back that they "stall" and tumble. You want a dart that cuts through the air or a glider that rides it. I’ve spent years tinkering with these, and the difference between a flop and a record-breaker is usually just a quarter-inch adjustment on the wing flaps.

The classic dart vs. the long-distance glider

Not all planes are built for the same job. You have to decide: do you want speed or hang time?

If you're in a narrow hallway, you want a dart. These are sleek. They have narrow wings and a heavy nose. The "Nakamura Lock" is a legendary example of this style—it’s a design by Ken Blackburn, who held the Guinness World Record for paper plane flight duration for years. His design isn't just a simple triangle; it involves a blunted nose that shifts the weight forward, preventing the plane from flipping over.

On the flip side, if you’re outside or in a gym, you want a glider. Gliders have massive surface areas. Think of a hawk versus a falcon. The hawk has wide wings to catch every bit of rising air, while the falcon is built to drop like a stone. Most people try to throw gliders too hard. Don't do that. A glider needs a gentle release, almost like you're setting it on a shelf in the air. If you hurl a wide-wing plane, the paper will just deform under the pressure and spiral out of control.

Why your paper choice is ruining your flight

Seriously, stop using construction paper. It’s too heavy and the fibers are too loose.

Standard 20lb (80gsm) office paper is the gold standard for a reason. It’s got the right balance of stiffness and weight. If you go too light, like tissue paper, the wings will flop. If you go too heavy, the plane becomes a brick. Also, humidity matters. If you’re trying to fly a plane in a damp basement, the paper absorbs moisture, gets heavy, and loses its crispness. Keep your "fleet" in a dry place.

The step-by-step to the world record style fold

Let's get into the actual folding. This isn't your standard "schoolyard special." This is a variation of the Suzanne, the plane John Collins used to break the world distance record (226 feet and 10 inches, if you're keeping track).

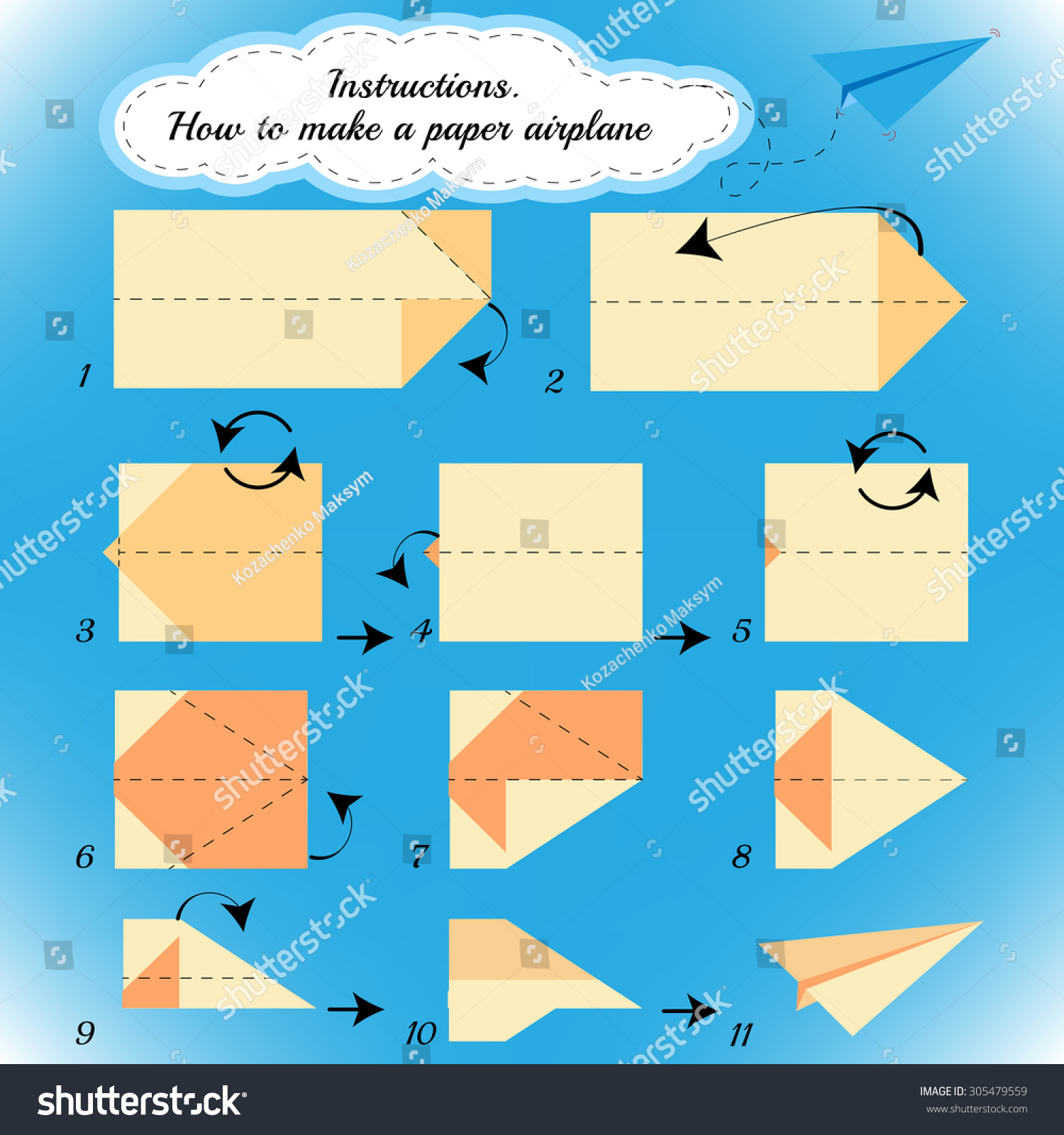

First, get a clean sheet of A4 or Letter paper. Crease it down the middle lengthwise, then open it back up. Now, fold the top corners into that center line. You've done this before. But here is the trick: instead of folding those edges into the center again immediately, fold the top "peak" down so it looks like an envelope.

✨ Don't miss: Why Pictures of Water Bottle Styles are Changing How We Hydrate

This creates a heavy "power-nose."

Now, fold the new top corners into the center, but leave about a half-inch of the previous fold sticking out at the bottom. Fold that little triangle "tab" up over the corners to lock them in place. This is the "Nakamura" style lock. It keeps the plane from unfolding mid-air when it hits a wall or high-speed wind. Finally, fold the whole thing in half away from you and fold the wings down.

The wings should be big. Don't make the body of the plane too tall. You want the wings to start about an inch from the bottom of the "fuselage."

The "Dihedral" secret most people miss

Look at your plane from the front. Are the wings flat? If so, it’s going to crash.

You want your wings to form a slight "V" shape. This is called a dihedral angle. In aeronautics, this provides lateral stability. If the plane starts to tilt to the left, the left wing becomes more horizontal, creating more lift, which naturally pushes the plane back to a level position. It’s a self-correcting mechanism. If your wings are drooping down (anhedral), the plane will be "unstable" and likely roll into a spiral dive the moment it leaves your hand.

Tuning your plane like a pro

A great fold is only 70% of the battle. The rest is "tuning."

Even the best paper plane in the world will fly like junk if it’s not tuned. If your plane keeps diving into the ground, you need to add "up-elevator." Use your fingernails to slightly—and I mean slightly—curl the back edges of the wings upward. This forces the tail down and the nose up.

But be careful. Too much up-elevator causes a "stall-and-fall" pattern.

The plane will climb steeply, lose speed, and then drop like a rock. You’re looking for a smooth, straight line. If the plane veers left, bend the back of the vertical tail (if it has one) or the back of the left wing slightly. It’s all about micro-adjustments. One millimeter can change everything.

Why the "throw" is often the problem

You can't just hurl every plane.

For a dart-style plane, you want a flick of the wrist, aiming slightly upward. For a glider, you want a long, smooth follow-through. Imagine you're throwing a dart at a board versus tossing a paper plate. Most people over-throw. They put so much power into it that the paper wings vibrate or "flutter," which creates massive drag and kills the flight instantly.

Smoothness beats power every single time.

✨ Don't miss: Why May 2025 Horoscope Lucky Signs Are All About This One Massive Jupiter Shift

Advanced aerodynamics for paper enthusiasts

If you really want to get deep into how to make a great paper plane, you have to look at wing loading. Wing loading is the total weight of the plane divided by the surface area of the wings.

Professional paper pilots (yes, they exist) often use "winglets"—those little vertical flaps at the tips of the wings. You see them on Boeing 747s. They reduce "wingtip vortices," which are basically little tornadoes of air that drag on the plane. By folding up the last half-inch of each wing tip, you can actually make your plane fly further by reducing that invisible drag.

It sounds like overkill for a piece of paper. It isn't.

Common mistakes to avoid

- Using tape: Unless you're following a specific design that requires it, tape usually just adds dead weight. If your folds are crisp, the paper should hold its own shape.

- Too many folds: Every time you fold the paper, you make it stiffer, but you also add thickness. Thick edges create drag. Keep your folds clean and use a bone folder (or the side of a pen) to make them razor-sharp.

- Symmetry issues: If one wing is even a tiny bit larger than the other, the plane will circle. Check your symmetry by looking at the plane from the bottom.

How to take your paper flight to the next level

Once you've mastered the basic dart and the locked-nose glider, start experimenting with different paper weights. Try 24lb paper for high-speed darts. It’s heavier, meaning it has more momentum once it’s moving.

If you're interested in the science behind this, check out the work of Ken Blackburn or John Collins (The Paper Airplane Guy). They have documented the specific physics of how a folded edge creates a boundary layer of air that helps the plane "slide" through the atmosphere. It’s genuinely fascinating stuff that moves way beyond simple hobbyist folding.

Next Steps for Better Flight:

- Switch to 20lb Paper: Grab a fresh sheet of printer paper; avoid the wrinkled stuff from the bottom of the stack.

- Focus on the Nose: Ensure your nose folds are heavy and tight. A light nose leads to a plane that tumbles backward.

- Adjust the Dihedral: Ensure the wings are tilted slightly upward in a "V" shape before your next throw.

- Practice the "Soft Launch": Try throwing with 50% less power and focus on a perfectly straight release.

- Add Tiny Winglets: Fold up the edges of your wings by 5mm to see how it stabilizes the flight path in a drafty room.