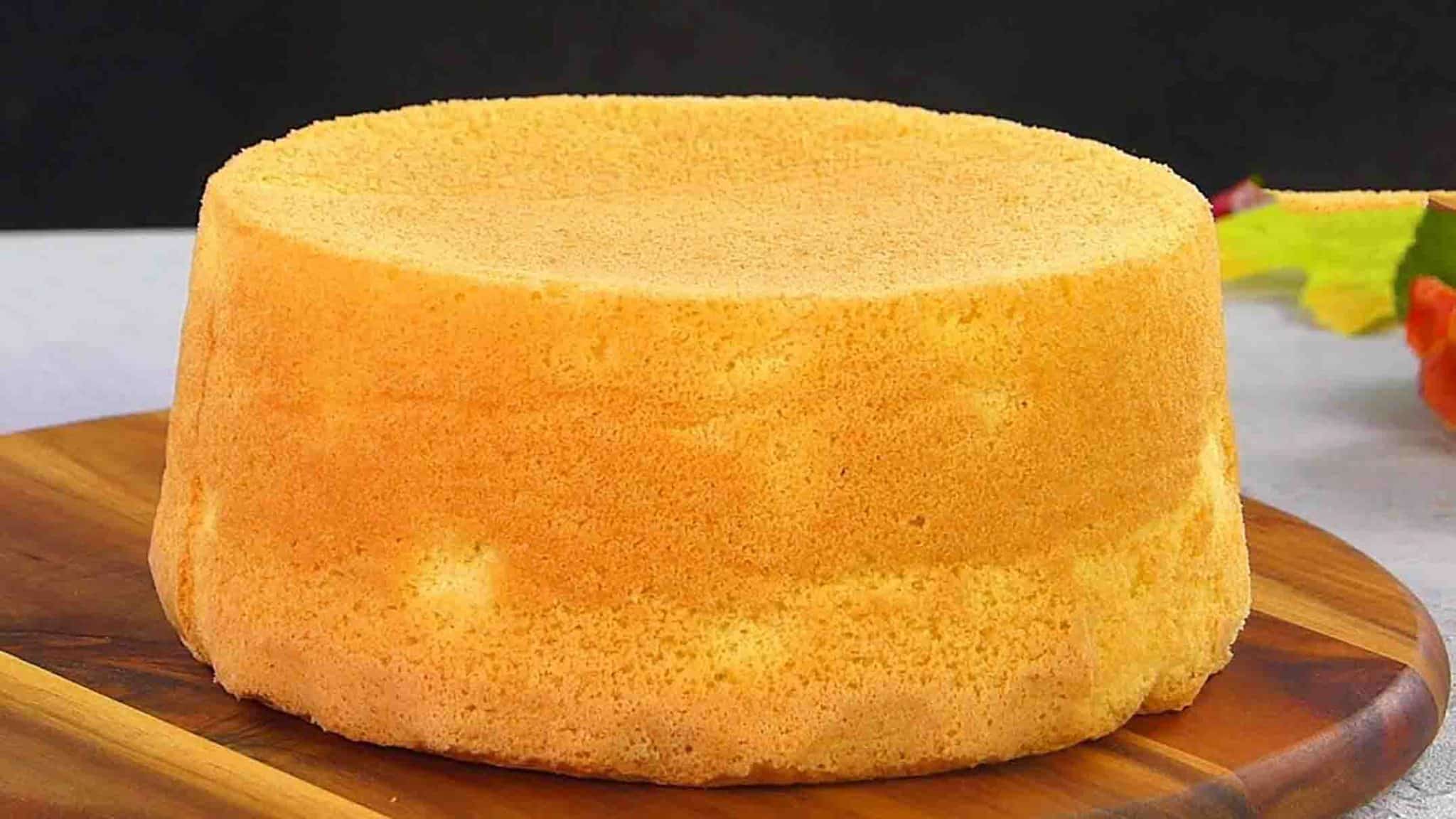

You've been there. The oven timer dings, you peek through the glass, and it looks glorious—a golden, towering mountain of fluff. Then you take it out. Within three minutes, that majestic dome turns into a wrinkled, sad pancake. It’s devastating. Honestly, learning how to make sponge cake recipe work for you is less about following a list of ingredients and more about understanding the physics of air.

Sponge cake isn't just "cake." It's an edible foam.

Most people treat it like a muffin or a pound cake where you just dump things in a bowl and stir. Do that here, and you’ll end up with a rubbery disc. A true sponge—specifically the Genoise or the classic Victoria style—relies almost entirely on the physical aeration of eggs. No baking powder is going to save you if you mess up the foam.

The Physics of the Foam

The whole "secret" is the protein structure of the eggs. When you beat eggs, you’re essentially forcing air into a protein net. If you’re making a traditional Pâte à Génoise, you usually beat whole eggs and sugar over a bain-marie (a pot of simmering water) until they reach the "ribbon stage." This isn't just a fancy culinary term. It means when you lift the whisk, the batter falls back into the bowl and holds its shape for at least three seconds. If it disappears instantly, keep whisking. You aren't there yet.

Temperature matters more than you think. Cold eggs don't stretch. If you try to whip an egg straight from the fridge, the proteins are too tight. They won't trap air efficiently. Professional pastry chefs like Rose Levy Beranbaum, author of The Cake Bible, emphasize that eggs should be at least room temperature, or even slightly warmed, to achieve maximum volume.

But here is where everyone messes up: the folding.

You’ve spent ten minutes building this beautiful, fragile structure of air bubbles. Then you dump in the flour and stir it like you’re mixing cement. Stop. You need to use a spatula and cut through the center, scrape the bottom, and lift. It’s a "J" motion. Do it as few times as humanly possible. Every stroke of the spatula is literally popping the air you just worked so hard to get in there.

Why Your Sponge Cake Recipe Is Failing

Let’s talk about the flour. Don't use All-Purpose. Just don't. All-purpose flour has too much protein (gluten). When you mix it, that gluten develops and creates a tough, chewy texture. You want cake flour. It’s milled finer and has a lower protein content, usually around 7-8%. If you can't find it, you can make a DIY version by taking a cup of AP flour, removing two tablespoons, and replacing them with cornstarch. Sift it. Sift it three times. You want that flour to be like a cloud so it doesn't weigh down the egg foam.

Fat is the enemy of foam.

If even a tiny speck of egg yolk gets into your whites (if you're doing a separated egg sponge), they won't whip. Fat weighs down the air bubbles. This is why many traditional sponges contain little to no butter. However, a Genoise adds a bit of melted butter at the very end for flavor. The trick? Mix a small scoop of the batter into the melted butter first to lighten it, then fold that mixture back into the main bowl. It prevents the heavy fat from sinking straight to the bottom and deflating the whole thing.

The Oven Door Trap

I know you want to look. Resist the urge. Opening the oven door in the first 15 minutes causes a sudden temperature drop. The air bubbles inside the cake are still fragile and haven't set yet. That cold breeze causes them to contract, and the structure collapses before the flour proteins have "set" or coagulated. It's the most common reason for the "crater" effect.

Also, check your oven temperature. Most home ovens are liars. An oven set to 350°F might actually be 325°F or 375°F. Buy a cheap oven thermometer. For a sponge, a too-hot oven sets the outside before the inside can rise, leading to a cracked top and a raw middle.

Step-By-Step Mechanics of the Perfect Rise

- Prep the pan correctly. For a true sponge, do not grease the sides of the pan. I know, it sounds crazy. But the cake needs to "climb" the walls of the tin. If the walls are slippery with butter, the batter just slides back down. Line the bottom with parchment paper, but leave the sides bone dry.

- The Egg Stage. If using the separated method, whip your whites to medium-soft peaks. If you go to "stiff" peaks where they look dry and chunky, they won't incorporate into the batter smoothly, and you'll end up with white clumps in your finished cake.

- The Sift. Sift your flour from a height. This adds even more air.

- The Fold. Use a large metal spoon or a flexible silicone spatula. Work quickly but gently.

- The Drop. Once the batter is in the pan, drop it once on the counter from about three inches up. This pops any massive, uneven air bubbles so you get a fine, tight crumb instead of giant holes.

The Cooling Controversy

How you cool the cake is just as important as how you bake it. For certain types of sponges, like Angel Food or Chiffon (which are cousins to the basic sponge), you actually have to cool them upside down. This stretches the protein bonds while they cool, preventing gravity from squishing the cake. For a standard sponge, let it sit in the pan for exactly five minutes, then run a thin knife around the edge and flip it onto a wire rack. If you leave it in the pan too long, the steam will turn the crust soggy.

Variations You Should Know About

Not all sponges are created equal.

👉 See also: How Much Sugar Is in a Chick-fil-A Lemonade: The Truth Behind That Tart Refreshment

- Victoria Sponge: This is the British classic. It actually uses a "creaming method" (butter and sugar first) and includes baking powder. It's sturdier and more "cake-y" than a true sponge.

- Genoise: The French standard. Uses whole eggs whipped with sugar over heat. It’s lean, slightly dry, and meant to be soaked with simple syrup.

- Biscuit (Bwee-kwee): This is common in jelly rolls. The yolks and whites are whipped separately and then folded together. It’s very flexible, which is why it doesn't crack when you roll it up.

Real Talk on Ingredients

Use high-quality eggs. Since the eggs are 80% of the flavor and 100% of the structure, the cheap, watery ones from a bargain bin won't give you the same lift. Fresh eggs have stronger protein bonds. If you have access to farm-fresh eggs, use them. The yolks are deeper in color, which gives the cake that beautiful pale-yellow hue without needing artificial dyes.

And please, use a scale. Measuring flour by the "cup" is a crapshoot. One person's cup is 120 grams; another's is 150 grams because they packed it down. In a recipe this sensitive, 30 grams of extra flour turns a sponge into a brick.

Making It Your Own

Once you master the base, the variations are endless. You can fold in lemon zest (do it at the very end), or replace a portion of the flour with cocoa powder for a chocolate version. If you go the cocoa route, you must sift it. Cocoa is notoriously lumpy and will create bitter pockets of dust in your cake if you aren't careful.

Most people find the taste of a plain sponge a bit boring. It’s designed to be a canvas. In professional patisseries, a sponge is almost always brushed with a flavored syrup—think Grand Marnier, espresso, or just a simple vanilla bean syrup. This adds moisture and flavor that the lean batter lacks on its own.

Troubleshooting Common Disasters

Dense layer at the bottom: This is caused by under-mixing or "heavy" ingredients sinking. Usually, it happens when melted butter isn't properly emulsified into a small portion of batter before being added to the whole.

Gritty texture: Your sugar didn't dissolve. If you're whisking eggs and sugar, make sure the sugar is fine (caster sugar is best). If you can feel grains between your fingers when you rub the batter, keep whisking.

Tough crust: Too much sugar or the oven was too hot. The sugar carmelizes on the outside before the cake finishes rising.

Actionable Next Steps

To get started right now, don't just grab a bowl. First, go find a metal or glass bowl and wipe it down with a paper towel dipped in a little lemon juice or vinegar. This removes any trace of grease that might kill your egg volume. Then, set your eggs out on the counter for at least an hour.

Next, verify your equipment. A hand mixer works, but a stand mixer is better for getting that stable "ribbon stage" without your arm falling off. Finally, commit to not opening that oven door for the first 20 minutes. Your patience will be rewarded with a cake that actually stays tall.

Once you’ve baked the base, let it cool completely before you even think about slicing it. A warm sponge is too fragile to cut cleanly. Use a serrated knife and a sawing motion; never press down hard, or you’ll crush the very air cells you spent so much effort creating. Use this as a base for a strawberry shortcake or a layered gateau, and you'll realize why this finicky recipe has remained a staple of professional baking for centuries.