Japanese is a language of silence. It’s about what you don’t say as much as what you do. If you’ve spent any time watching anime or reading Murakami, you’ve probably heard the word ai. It sounds beautiful. It feels heavy. But here’s the thing: if you walk up to someone you’ve been dating for three weeks and drop an "Ai shiteru" on them, you might actually scare them away.

Seriously.

Understanding how to say love in Japanese isn't just about memorizing a dictionary entry. It’s a cultural minefield where the wrong word choice makes you sound like a 19th-century poet or a confused tourist. Japanese people rarely use the word "love" the way we do in English. We love pizza, we love our moms, and we love that new Netflix show. In Japanese, those are all very different buckets of emotion.

Why Suki is Actually Your Best Friend

Most beginners want to jump straight to the "big" words. Don't do that. Suki (好き) is the workhorse of Japanese affection. It technically translates to "like," but context is everything.

If you’re at a karaoke bar and tell someone "Suki da yo," you aren't just saying you like their vibe. You're often confessing a romantic interest. It’s safe. It’s versatile. You can use it for your favorite ramen shop, your favorite Nintendo character, or the person you want to marry.

To turn up the heat, you add dai (big) to get Daisuki (大好き).

This is where things get real. Daisuki is often the "I love you" of the Japanese world. It’s enthusiastic. It’s warm. It lacks the crushing, existential weight of formal "love" words but carries all the sincerity you actually need.

The Kokuhaku Culture

You can't talk about love in Japan without mentioning the kokuhaku. This is the formal confession of feelings. Unlike in the West, where you might "see where things go," Japanese dating often starts with a clear statement of intent. "Suki desu. Tsukiautte kudasai." (I like/love you. Please go out with me.)

Without this step, you’re often stuck in a weird limbo. Are you dating? Are you just friends who eat crepes together? Nobody knows until the words are said.

The Heavy Weight of Ai Shiteru

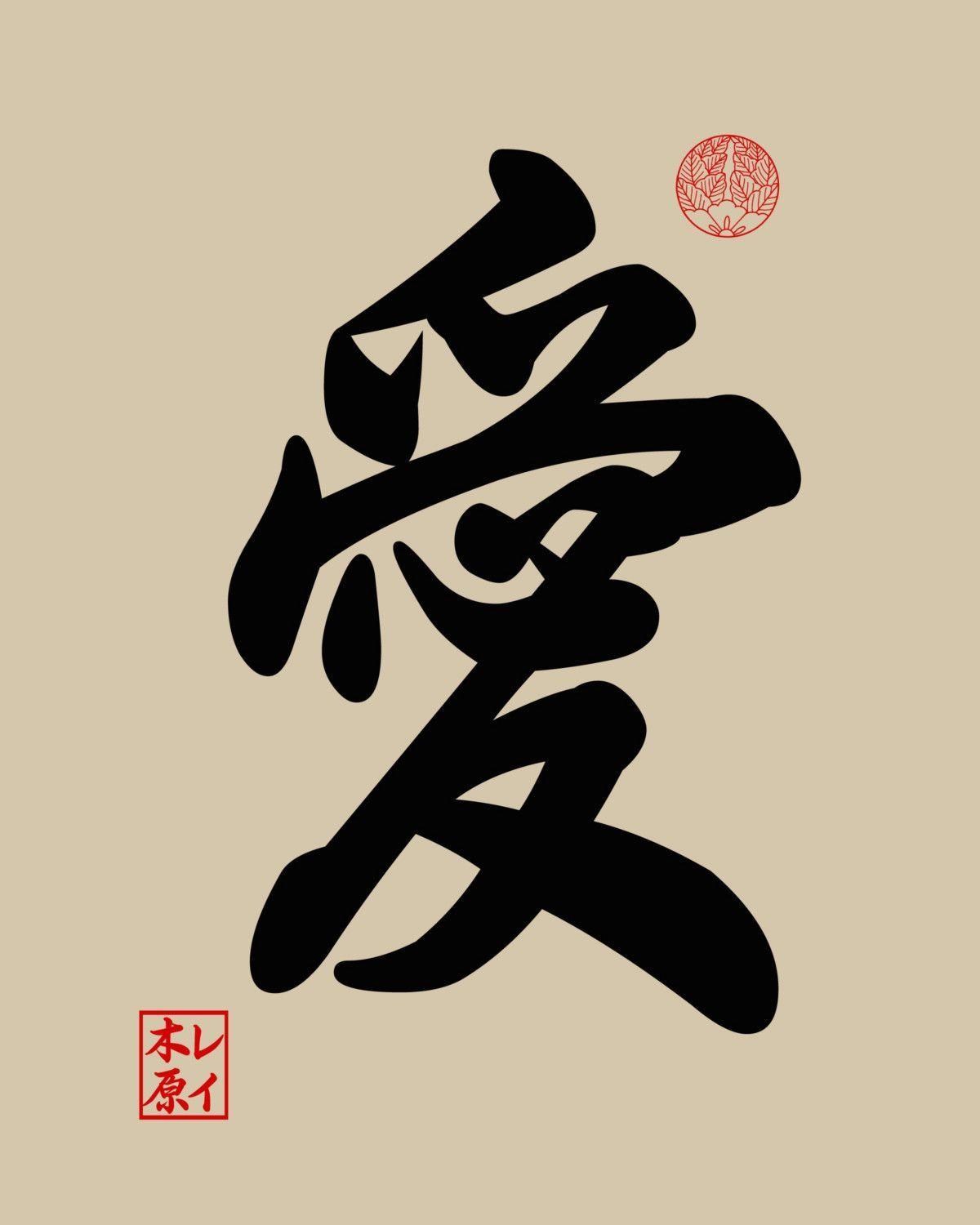

Now we get to the word everyone knows. Ai (愛).

In textbooks, Ai shiteru is the translation for "I love you." In reality? It’s rarely spoken. Japanese culture historically prizes enryo (restraint) and ishin-denshin (heart-to-heart communication without words). To say Ai shiteru is to make a grand, cinematic gesture.

Some Japanese couples go their entire lives without saying it once.

Anthropologists and linguists, like the late Takeo Doi, have written extensively about amae—the desire to be loved and cared for. This "dependency" is often a truer expression of love in Japan than a verbal declaration. Actions speak. Bringing someone an umbrella at the station when it starts raining is "Ai shiteru" in action. Washing the dishes without being asked is "Ai shiteru."

If you do use it, save it for:

📖 Related: West 83rd Street NYC: Why This Specific Upper West Side Block Feels Different

- Proposals.

- Deathbeds.

- Weddings.

- Long-term partners after years of shared struggle.

The Nuance of Koi vs. Ai

Japanese actually has two distinct characters for love, and they aren't interchangeable. Knowing how to say love in Japanese means knowing which side of the fence you're on.

Koi (恋) is selfish love. It’s the "butterfly in your stomach" feeling. It’s wanting someone. It’s often depicted as romantic longing or even "love sickness." It’s a bit messy.

Ai (愛) is selfless love. It’s giving. It’s the kind of love parents have for children, or partners have after the honeymoon phase is a distant memory.

When you combine them, you get Renai (恋愛), which refers to romantic love as a concept. If you’re looking for a "love marriage" (renai kekkon) vs. an arranged one, that’s your word.

Dialects and Modern Slang

Language isn't static. Young people in Tokyo or Osaka don't talk like a 1950s drama.

In the Kansai region (Osaka/Kyoto), you might hear Suki yanen. It’s punchy. It’s a bit more "down to earth." There’s even a famous brand of instant noodles with that name. It takes the pressure off.

📖 Related: Tripp Trapp Chair Infant Seat Explained (Simply)

Then there’s the "Internet speak." You might see te-te-re or other slang used in chat rooms to describe cute couples (toutoi - "precious"), but you’d never say these in a serious romantic moment.

Honestly, even the word "love" (rabu) has been imported as katakana English. You’ll see it on heart-shaped pillows or in pop songs. "Ai rabu yuu" is almost a joke—it’s so light that it doesn't carry any of the social risk of the Japanese equivalents.

Non-Verbal Cues: The "Invisible" Love

Since Japanese is a high-context culture, saying the words is often considered unnecessary or even "uncool."

There’s a famous (though possibly apocryphal) story about the novelist Natsume Soseki. He supposedly told his students that a Japanese person wouldn't say "I love you." Instead, they would say, "The moon is beautiful, isn't it?" (Tsuki ga kirei desu ne).

The idea is that if two people are sharing a moment, the beauty of the surroundings is enough to convey the depth of their connection. While nobody actually uses that phrase as a literal confession today (unless they're being incredibly nerdy or poetic), the sentiment remains.

If you want to show love in Japan:

- Pay attention to the small details.

- Use Suki for the early stages.

- Keep Ai shiteru in your back pocket for the "big" moments.

- Don't force it.

The silence between two people is often where the real "love" lives.

Practical Steps for Your Next Move

If you're actually planning on telling someone how you feel, keep it simple. Overcomplicating the grammar just makes you look like you're reading from a script.

- For a first confession: Stick to "Suki desu." It’s clean, it’s honest, and it leaves room for the other person to breathe.

- For your long-term partner: Try "Itsumo arigato" (Thank you for everything/always). In many ways, gratitude is a higher form of affection in Japan than "love" itself.

- For family: Don't say "I love you." It's weird in a Japanese family context. Instead, focus on "Otsukaresama" (Good job/Thank you for your hard work) or simply buying them a gift they like.

Language is a tool, but culture is the manual. Use the right tool for the right job and you'll avoid the "gaijin" awkwardness that comes from over-sharing. Understand that in Japan, love is a verb, not just a noun you throw around. It's in the tea they pour for you and the way they wait for you at the ticket gate. Listen for those silences. That's where the real "love" is hidden.