You’ve probably seen it gathering dust in the corner of a CrossFit box or tucked under a bench at your local YMCA. It’s basically just a plastic wheel with a stick through it. Simple, right? But the ab wheel is easily one of the most deceptive pieces of equipment in the entire fitness world. It looks like a toy. It feels like a torture device. If you use it wrong, it’s a one-way ticket to a "twinge" in your lumbar spine that stays for a week.

Most people treat the rollout like a stretching exercise. They shove the wheel out as far as they can, let their hips sag toward the floor, and then wonder why their abs don't hurt but their lower back feels like it's being pinched by a pair of pliers. Honestly, it's because the ab wheel isn't an "ab cruncher" in the traditional sense. It is an anti-extension powerhouse. Your goal isn't to move the wheel; it's to stop your spine from collapsing into a literal U-shape while gravity tries its best to pull your belly to the turf.

The Biomechanics of Why You’re Failing

Let’s talk about the rectus abdominis. Most people think of this muscle—the "six-pack"—as something that brings your chest to your knees. While it does that, its more functional job in a rollout is to keep your pelvis tucked. Dr. Stuart McGill, a world-renowned expert in spine biomechanics at the University of Waterloo, has spent decades studying how we stabilize our core. He often emphasizes that "stiffness" is the goal for spinal health. When you learn how to use an ab wheel, you aren't looking for flexibility. You are looking for a rock-solid, isometric brace.

If you let your back arch, you are no longer training your core. You are hanging on your ligaments.

The movement starts long before the wheel even rolls an inch. You have to find what's called a posterior pelvic tilt. Think of it as tucking your tailbone between your legs like a scared dog. If you start with a "duck butt" (anterior tilt), you've already lost the battle. Your hip flexors—specifically the psoas—will take over the movement. Since the psoas attaches directly to your lumbar vertebrae, it will literally pull on your spine as you roll out. That's the source of that nasty "pinching" feeling.

Setting Up Your First Rep

Don't just jump into it. Grab a yoga mat or a foam pad for your knees because the pressure on your patella can be distracting.

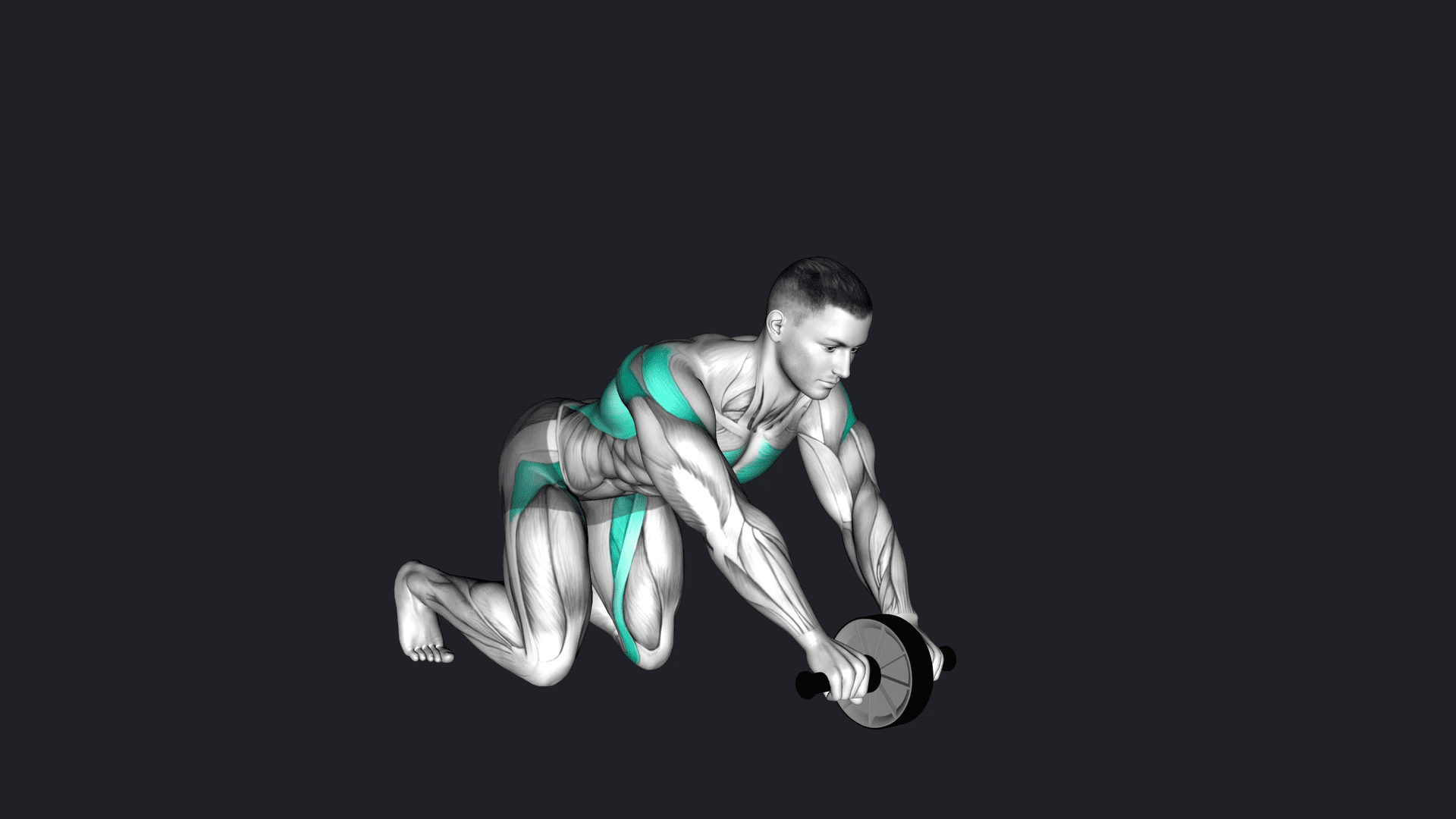

Position the wheel directly under your shoulders. Now, look at your spine. You want a "hollow body" position. This means your upper back should be slightly rounded—kinda like a cat—and your abs should be squeezed tight before you move.

- The Grip: Don't white-knuckle the handles. Hold it firm, but keep your wrists straight. If your wrists flop back, you're losing force transfer.

- The Breath: Big inhale into your belly. Hold it. This creates intra-abdominal pressure. It’s like inflating a tire inside your torso to keep the rim from hitting the ground.

- The First Inch: Slowly push the wheel forward. Stop. Do you feel your lower back arching? If yes, that's your current "end range."

Many beginners try to go all the way to the floor on day one. That's a mistake. It’s better to roll out eighteen inches with a perfect spine than three feet with a broken one. You’ve got to respect the lever arm. The further the wheel gets from your knees, the heavier your torso becomes. It's basic physics.

Why Your Hip Flexors Are Cheating You

There is a common mistake where people sit back on their heels at the end of the rep. You roll out, then you pull the wheel back by shoving your butt toward your feet.

Stop doing that.

🔗 Read more: Bottoming for the First Time: What You Actually Need to Know to Make it Pleasant

When you sit back, you're using your hips to move, not your abs. To keep the tension where it belongs, your hips should never go further back than your knees. Keep your weight shifted forward. Your arms and your torso should move as one unit. Imagine your armpits and your hips are connected by a steel rod that cannot change length.

If you struggle with this, try the "wall stop" method. Face a wall and roll out until the wheel hits the baseboard. This acts as a physical limit, preventing you from overextending into a range you can't control yet. As you get stronger, move a few inches further back from the wall. It’s a built-in progress bar for your strength.

Advanced Variations and Common Myths

Some people say you need to do standing ab wheel rollouts to see real results. Honestly? Most people never need to do a standing rollout. It is an incredibly high-tension move that requires elite-level posterior chain strength. For 95% of the population, the kneeling version provides more than enough stimulus to build a bulletproof core.

If you do want to level up, try changing the tempo.

- The 5-5-5 Method: Spend 5 seconds rolling out, hold the bottom position (just an inch off the floor) for 5 seconds, and take 5 seconds to roll back. The time under tension will make your abs scream way more than doing 50 fast, sloppy reps.

You can also try "V-rolls." Instead of going straight, roll at a slight angle to the left, then the right. This brings the internal and external obliques into the mix. These muscles are responsible for rotation and lateral stability. By adding a directional change, you're forcing them to resist the pull of gravity from different angles.

💡 You might also like: Is it safe to take melatonin: The truth about your sleep hormones

Real Evidence: What the Science Says

A study published in the Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy compared various core exercises, including the crunch, the plank, and the ab wheel. The researchers found that the ab wheel rollout was one of the most effective exercises for eliciting high levels of electromyographic (EMG) activity in both the upper and lower rectus abdominis. However, it also showed high activity in the latissimus dorsi.

Wait, the lats?

Yes. The lats are a primary stabilizer in this movement because they are responsible for shoulder extension. If your back is sore after a heavy ab wheel session, it might actually be your lats. This is normal. Just make sure it’s the "meaty" part of your back that’s sore, not the spine itself.

Troubleshooting the "Snap"

If you feel a "snap" or a "pop" in your shoulders, you're likely over-reaching. People with limited shoulder mobility often try to force their arms overhead, which impinges the rotator cuff. If your shoulders feel sketchy, don't roll out as far. Keep the wheel slightly in front of your eye line rather than letting it get way past your head.

Also, check your head position. Don't look up at the wall in front of you. That puts your cervical spine into extension, which usually leads to your lower back following suit. Keep your gaze tucked down, looking at the floor about a foot in front of the wheel. Think "long neck."

Practical Progression Path

Don't just wing it. Follow a path that respects your connective tissue.

Phase 1: The Isometric Hold

Instead of rolling, just get into the "out" position and hold it for 30 seconds. If you can't hold a plank with a hollow body, you have no business moving the wheel yet.

Phase 2: The Limited Range Rollout

Use the wall stop. Set the distance so you can do 10 reps with zero back pain. If rep number 11 feels "tweaky," stop.

✨ Don't miss: The Truth About Meals to Make to Lose Weight and Why Your Salad Is Failing You

Phase 3: The Full Kneeling Rollout

Go all the way down until your chest is an inch from the floor. Pause. Use your abs—not your arms—to pull yourself back up.

Phase 4: The Weighted or Banded Rollout

Wear a weighted vest or have a partner loop a resistance band around your waist. This adds a horizontal resistance component that makes the "return" phase much harder.

Actionable Next Steps

To actually master how to use an ab wheel, you need frequency, not just intensity. The core recovers relatively quickly compared to the legs or chest.

- Start with 2 sessions per week. Do 3 sets of 8-10 controlled reps.

- Film yourself from the side. This is the only way to see if your back is arching. What feels "flat" to you is often a massive arch in reality.

- Prioritize the "tuck." If you lose the posterior pelvic tilt, the set is over. No exceptions.

- Integrate it. Use the ab wheel at the end of your workout as a "finisher." Since it requires so much stability, you don't want to fatigue your core right before doing heavy squats or deadlifts.

The ab wheel is a humbling tool. It doesn't care how much you bench. It only cares if you can maintain tension under pressure. Stay tight, keep the wheel close, and stop chasing the floor until your core has earned the right to be there.