You're looking at a chart. The line is going up. That’s good, right? But something feels off. The curve isn't a steep rocket ship anymore; it’s starting to round out like the top of a hill. You’re still making more money, gaining more followers, or losing more weight than you had yesterday, but the extra amount you added today is smaller than the extra amount you added last week.

This is the weird, often frustrating reality of increasing at a decreasing rate.

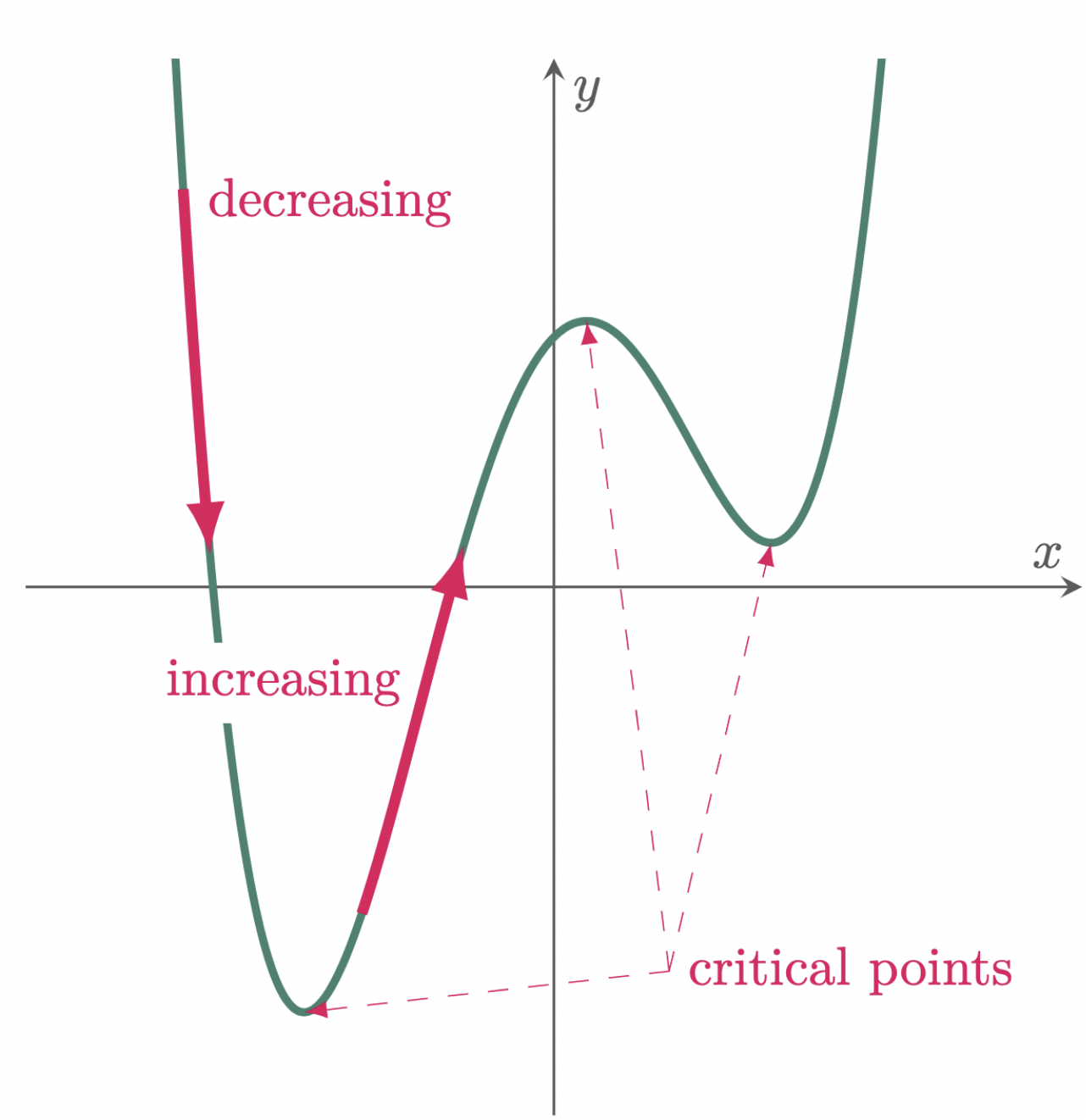

It’s a mathematical state of being that messes with our heads. In calculus, we call it a positive first derivative and a negative second derivative. In plain English? You’re still winning, but you’re winning more slowly. If you don't understand this phase of growth, you’ll probably panic and pivot right when you should actually be optimizing.

The Plateau That Isn't Actually a Plateau

Most people mistake this phase for a dead end. They see the growth curve flattening and assume they've hit a ceiling.

They haven't.

Think about a professional sprinter. When a kid starts training, they might shave four seconds off their 100-meter dash in a single summer. That’s massive. A few years later, they’re training twice as hard just to shave off 0.05 seconds. Their speed is still increasing, but it is increasing at a decreasing rate. The gains are getting harder to squeeze out of the system. This is the "Law of Diminishing Returns" in the flesh.

Economist David Ricardo talked about this back in the 19th century regarding agriculture. If you have a patch of land and you keep adding more workers, eventually, they start getting in each other's way. You’ll get more crops with ten workers than with nine, sure. But the jump from nine to ten workers produces less "extra" food than the jump from one to two did.

Real-World Examples of the Curve in Action

You see this everywhere once you know what to look for. It’s the "S-Curve" of innovation.

- The Smartphone Market: Between 2007 and 2012, every new iPhone was a generational leap. Now? The cameras get slightly better. The processor is 10% faster. Apple is still growing its ecosystem, but the rate of radical change has slowed down significantly.

- Weight Loss: In the first week of a new diet, you might drop five pounds. It's mostly water, but it feels incredible. By month six, you're fighting for every half-pound. You're still getting thinner (increasing your total weight loss), but the pace has shifted.

- Social Media Virality: A video goes viral. In hour one, you get 10,000 views. In hour two, 50,000. By hour twenty, you're at 2 million views, but you're only gaining 5,000 new views per hour. The total is still climbing. The momentum, however, is flagging.

Why This Happens (The Technical Bit)

Basically, you've picked the low-hanging fruit.

When you start a business, the first $10,000 in revenue is often about just showing up. You sell to friends, family, and that one guy on LinkedIn who buys everything. To get from $10k to $100k, you need a real process. To get from $1 million to $2 million, you’re fighting for market share against entrenched competitors.

The "input" required to generate the next unit of "output" keeps rising.

Mathematically, if we define your growth as a function $f(x)$, then $f'(x) > 0$ (the slope is positive) but $f''(x) < 0$ (the curve is concave down). It's the moment before the peak. It’s the transition from "early-stage chaos" to "mature-stage optimization."

Don't Let the Math Scare You Into Quitting

The biggest danger of increasing at a decreasing rate is the psychological toll.

We are addicted to the "hockey stick" graph. We want exponential growth forever. But exponential growth is actually pretty rare in nature—it usually turns into logistic growth. If you expect a straight line up forever, you’ll see a slowing growth rate as a sign of failure.

📖 Related: Why an Interest Rate Return Calculator is the Only Way to See Through the Bank's Hype

It’s not. It’s actually a sign of maturity.

If you’re a manager and your team’s productivity is increasing at a decreasing rate, it might mean they are reaching peak efficiency. Pushing them harder won't necessarily result in a return to that early, rapid growth. It might just result in burnout. At this stage, you stop looking for "more" and start looking for "better."

You shift from customer acquisition to customer retention.

You shift from feature bloating to user experience.

How to Handle the Slowdown

- Change Your Metrics: Stop obsessing over the percentage growth month-over-month if you're already a market leader. Focus on the raw numbers or, better yet, profit margins.

- Look for New Curves: If your current product is increasing at a decreasing rate, it might be time to launch something new. This is what Netflix did when DVD sales slowed down—they jumped to streaming. They started a new S-curve before the old one flattened out completely.

- Optimize the Process: When growth is easy, you can be messy. When growth is hard, you have to be precise. This is the time to cut the fat and find the 1% gains.

- Accept the Natural Limit: Everything has a carrying capacity. A pond can only hold so many fish. A market can only hold so many subscribers. Recognizing where you are on the curve prevents you from making desperate, value-destroying moves.

Actionable Next Steps

Check your data. Don't just look at the total numbers; look at the velocity.

If you realize you’re in a phase of increasing at a decreasing rate, do a deep dive into your marginal costs. Calculate exactly how much effort (time or money) it took to get your last ten customers versus your first ten. If that cost is ballooning, don't just throw more money at the problem.

Instead, look for ways to increase the value of the customers you already have. Upsell, cross-sell, or improve your churn rate. When you can't grow "out" anymore, you have to grow "deep." This is how sustainable businesses survive the transition from a "hot startup" to an "industry staple."

Stop comparing your current pace to your "day one" pace. It’s a different game now. Play it accordingly.