It is rare to find a book that feels like a physical weight in your hands, not because of its page count, but because of the sheer density of its emotional gravity. Published in 1999, Interpreter of Maladies didn't just win the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction; it fundamentally shifted how the Western literary world looked at the Indian diaspora. Jhumpa Lahiri did something remarkably quiet. She didn't rely on sprawling epics or magical realism. Instead, she looked at the crumbs on a dinner table, the way a husband looks at a wife he no longer knows, and the crushing silence of a miscarriage.

Honestly, it's a gut-punch of a collection.

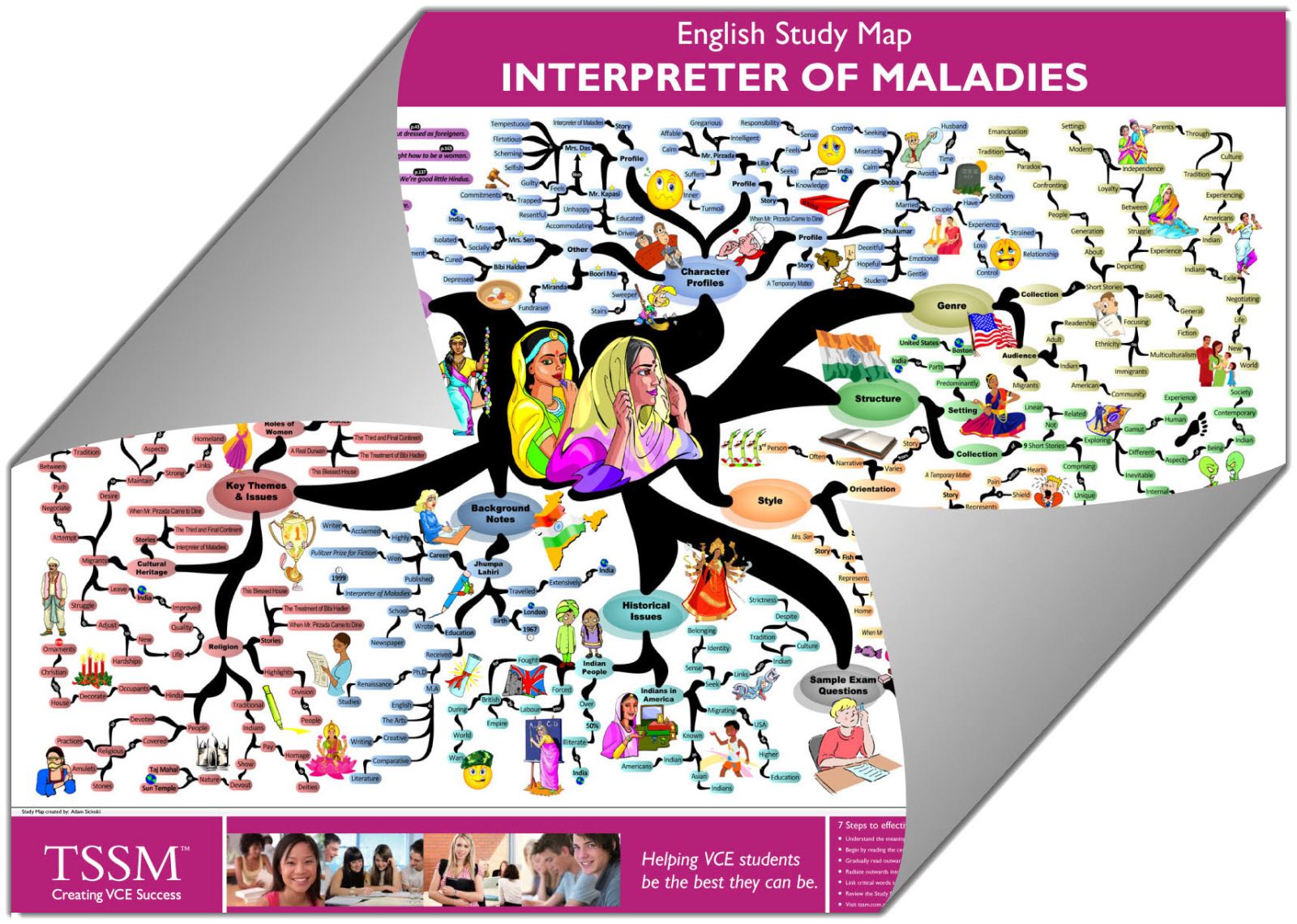

Most people coming to this book for the first time expect a singular narrative. It isn't that. It’s nine distinct stories that explore the bridge—often a broken one—between India and New England. You’ve got characters who are physically in America but emotionally stuck in Calcutta, and others who are so "Americanized" they feel like tourists in their own heritage. It’s about the "maladies" we can’t name.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Interpreter of Maladies

A common misconception is that this is a "book about India." That’s a bit of a surface-level take. If you look closer, it’s actually a book about the failure of communication. The title story, "Interpreter of Maladies," is the perfect example of this. We meet Mr. Kapasi, a man who spends his weekdays translating symptoms for a doctor because his patients speak a language the doctor doesn't. On weekends, he moonlights as a tour guide.

He meets the Das family, Indian-Americans visiting the sun temple at Konark. They look Indian, but they act like total foreigners. Mrs. Das, played out in her mini-skirt and puffed rice, confesses a dark secret to Kapasi because she thinks his job as an "interpreter" means he can somehow absolve her of her guilt. She mistakes translation for transformation. It’s a devastating misunderstanding.

👉 See also: How Many Centimeters Are There in an Inch: The Math Everyone Gets Wrong

The malady isn't a disease. It's the distance between two people sitting in the same car.

The Nuance of the Immigrant Experience

Lahiri’s writing is famous for its "plain style." There are no flowery metaphors. In "A Temporary Matter," a couple deals with a rolling blackout in their suburban home. They use the darkness to confess things they’ve been hiding since the birth of their stillborn child. It’s brutal. The prose is so clean it almost feels clinical, which makes the emotional reveals feel like a slap in the face.

You see this theme of "displacement" everywhere. In "Mrs. Sen's," a young boy watches an immigrant woman struggle to learn how to drive. For Mrs. Sen, driving represents a terrifying leap into American life, while chopping vegetables with a traditional boti from India is her only source of comfort. When she fails at one, she loses her grip on the other. It’s a small story, but it carries the weight of every person who has ever felt like they didn't belong in their own zip code.

Why the "Maladies" Still Matter Today

You might wonder why a book from 1999 is still topping "must-read" lists in 2026. Basically, the world has only gotten more fragmented. While we have better technology to "connect," the actual interpretation of our feelings hasn't gotten any easier.

- The "In-Between" Identity: Second-generation immigrants still struggle with the exact same tensions Lahiri described—feeling too "Western" for their parents and too "Eastern" for their peers.

- The Domestic Silence: The book explores how marriages die not from big fights, but from things left unsaid.

- Cultural Consumerism: We see how tourists (like the Das family) treat culture as a backdrop for their own personal dramas.

In "The Third and Final Continent," which is probably the most hopeful story in the bunch, the protagonist navigates the strangeness of a new marriage and a new country. He lives in a YMCA, then moves into a room owned by a 103-year-old woman named Mrs. Croft. It’s a story about the weird, accidental connections we make. It reminds us that while translation is hard, it’s not impossible.

Looking at the Craft: Why Writers Study This Book

If you’re a writer, you study Interpreter of Maladies for the "objective correlative." That’s just a fancy way of saying Lahiri uses objects to represent feelings.

Consider the boiled eggs in "The Treatment of Bibi Haldar" or the silk scarves in "When Mr. Pirzada Came to Dine." These aren't just props. They are anchors. Mr. Pirzada, a man from East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) during the 1971 war, carries a pocket watch set to the time in Dacca. He’s physically in New England, eating dinner with a young girl’s family, but his heart is ticking in a war zone.

That watch is the story. You don't need a thousand words describing his grief when you have the watch.

Actionable Insights: How to Approach the Text

If you’re reading this for a book club, a class, or just personal growth, don't just rush through the plots. These stories are meant to be chewed on.

1. Track the Food

Notice how cooking and eating change based on the character’s emotional state. When the characters are disconnected, they eat takeout or cereal. When they are trying to find their way back to themselves, the preparation of food becomes a ritual.

2. Watch the Silence

In almost every story, there is a moment where a character decides not to say something. Highlight those moments. That’s where the "malady" lives.

3. Compare the Generations

Look at the difference between the characters born in India and those born in America. There is a specific kind of resentment that flows both ways—the parents fear their children are losing their soul, and the children feel their parents are anchors holding them back from the "modern" world.

4. Research the Context

While the stories are universal, knowing a bit about the Partition of India or the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War adds layers to stories like "When Mr. Pirzada Came to Dine." It turns a domestic story into a political one.

Lahiri’s work reminds us that everyone is carrying a symptom of some unspoken hurt. Whether it’s the grief of a lost child, the boredom of a stale marriage, or the loneliness of a new city, we are all looking for someone to interpret what we’re going through. Sometimes the best we get is a brief, flickering moment of understanding before the lights go back on.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Understanding:

- Read "A Temporary Matter" and "The Third and Final Continent" back-to-back; they represent the two extremes of Lahiri's outlook on love.

- Explore Lahiri's later work, like The Namesake, to see how she expands these themes into a full-length novel format.

- Compare the "tourist gaze" in the title story to your own experiences traveling—ask yourself if you are truly seeing the culture or just using it as a mirror for your own life.