You’re standing in the kitchen, probably staring at a recipe that looks like it was written in a different language, or maybe you're just trying to figure out if that expensive engine oil is actually a good deal. Most of us grew up thinking a quart and a liter are basically the same thing. They’re cousins. Close enough, right?

Well, honestly, if you try to fit 4 quarts in a liter, you’re going to have a very messy floor.

It sounds like a simple math problem, but it’s actually a collision of two completely different historical philosophies: the British Imperial system and the French Metric system. People search for this because they want to know if they can swap one for the other. The short answer is a hard "no." In fact, a liter is significantly smaller than four quarts. It's not even close. To be precise, four quarts is roughly 3.78 liters. If you’re trying to go the other way—putting four quarts into a single liter container—you’d need to find a way to compress liquid, which, as any high school physics teacher will tell you, isn't really a thing.

Why 4 Quarts in a Liter is the Wrong Way to Think About It

We have to look at the actual volume to understand why this trips people up. A US liquid quart is 946.35 milliliters. A liter is 1,000 milliliters. So, a liter is actually bigger than a single quart by about 5%. This is where the confusion starts. Because a liter is slightly larger than a quart, people assume that "four" of something must fit into the "bigger" unit.

But scale matters.

When you bundle four quarts together, you get a gallon. That’s 3,785 milliliters. Comparing that to a 1,000-milliliter liter is like trying to park a suburban SUV in a spot meant for a Vespa. You’ve got nearly four times the volume in those four quarts. It’s a common mix-up because the words sound similar and they occupy the same "vibes" in our heads when we're shopping for milk or soda.

The "Close Enough" Trap in the Kitchen

I’ve seen plenty of home cooks shrug and say, "Eh, a quart is a liter." In small amounts, like a single cup of chicken stock, you probably won't ruin dinner. But let’s talk about baking. Baking is chemistry, not just "cooking." If you’re making a massive batch of base for a wedding cake and you swap four liters of milk for four quarts, you are missing about 215 milliliters of liquid.

That’s nearly a whole cup of fluid gone.

Your cake will come out dry, crumbly, and sad. The NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology) keeps these measurements exact for a reason. Even in automotive care, if your engine calls for four liters of oil and you only put in four US quarts, you are running dangerously low. You’re missing over 5% of the required lubrication. Over time, that creates heat. Heat creates friction. Friction creates a very expensive trip to the mechanic.

The History of Why We Have This Mess

It’s easy to blame the French, but they actually tried to simplify things. Before the French Revolution, Europe had thousands of different measuring units. A "pint" in one village might be 20% larger than a "pint" in the next town over. It was a nightmare for trade. In 1795, the French Republic defined the liter as a cubic decimeter. It was clean. It was based on the Earth (sort of).

Meanwhile, the US stuck with the British Wine Gallon from the 1700s.

This is the real kicker: there are actually two different kinds of quarts. There’s the US Liquid Quart and the UK Imperial Quart. If you’re in London, an Imperial Quart is actually larger than a liter (it’s about 1.13 liters). So, if you’re a British traveler wondering about 4 quarts in a liter, you’re even further off the mark! Four UK quarts would be over 4.5 liters.

Breaking Down the Math (The Painless Way)

Let’s look at the actual numbers because seeing them side-by-side usually clears up the brain fog.

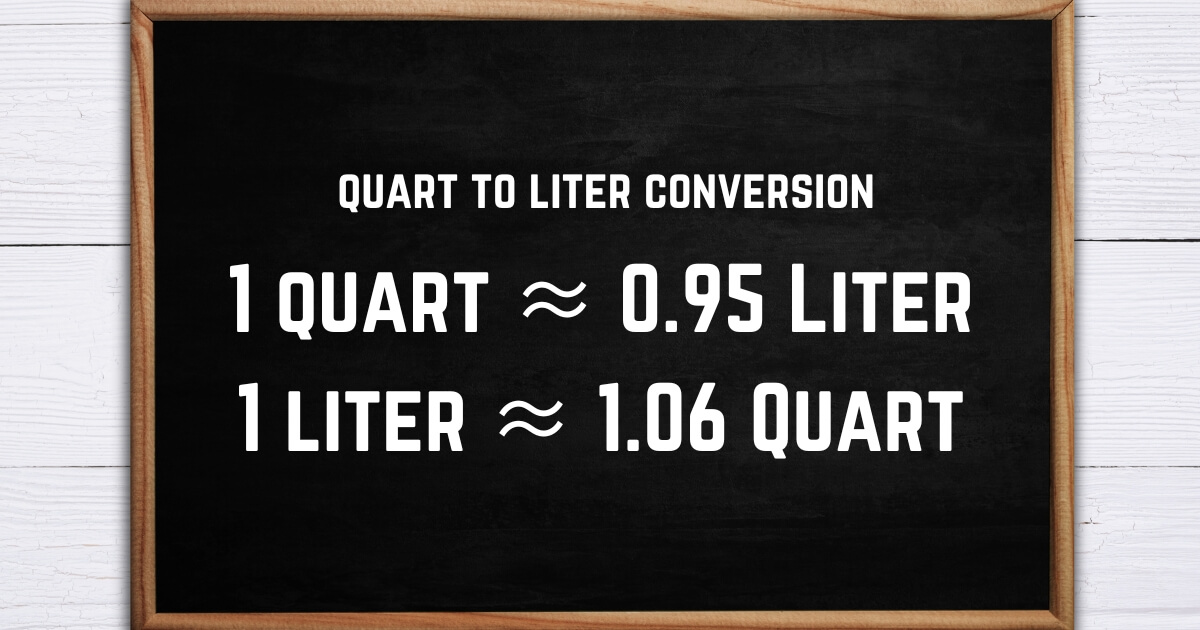

1 US Liquid Quart = 0.946 Liters

1 Liter = 1.056 US Liquid Quarts

If you have 4 quarts, you have 3.785 liters.

If you have 4 liters, you have 4.226 quarts.

It’s a lopsided relationship. You can’t just swap them 1:1 unless you’re okay with a 5% margin of error, which, in medicine or chemistry, is enough to be catastrophic. Dr. William Kitchener, a famous 19th-century cookbook author, used to complain about the lack of standardized measures because it made sharing recipes across borders nearly impossible. We are still living in that world today, just with better calculators on our phones.

Real World Consequences of the Conversion Fail

Imagine you’re a contractor. You’re mixing a specialized sealant for a high-end pool deck. The instructions call for a 4-liter mixture. You buy four quarts of the base chemical. You’ve just short-changed your mixture by nearly a cup of fluid. The chemical reaction won't trigger correctly. The sealant stays tacky. It never cures. Now you’re stripping a deck and losing thousands of dollars because of a "close enough" mentality.

This happens in the marine industry too. Boat fuel tanks are often rated in liters internationally but sold in gallons/quarts in the US. If you’re calculating your "range to empty" and you confuse your 4-quart intervals with liters, you might find yourself stranded three miles offshore with a dry tank and a very frustrated family.

Why Does This Keep Happening?

Visual bias. A 1-liter Nalgene bottle and a 32-ounce (1-quart) Gatorade bottle look almost identical to the naked eye. Our brains are wired to categorize things by their physical footprint. Since a 1-liter bottle is roughly the same height and width as a 1-quart bottle, we assume they are interchangeable.

🔗 Read more: The Time of Sunset in Seattle and Why It Changes Your Life

They aren't.

That extra 54 milliliters in the liter bottle is the "hidden volume" that messes everyone up. It’s the reason why a "2-liter" soda bottle feels so much more substantial than a half-gallon (2-quart) carton of milk. Because it is. It’s actually 2.11 quarts.

Practical Tips for Not Ruining Your Project

If you find yourself needing to convert between these two, stop guessing. Honestly, just stop. Here is how you actually handle the "4 quarts in a liter" problem in the real world:

First, identify your source. Are you looking at a recipe from a UK-based site like BBC Good Food? If so, their "quart" isn't even the same as a US quart. Use a digital scale if you can. Measuring by weight (grams) is the only way to bypass the quart-vs-liter headache entirely. Water-based liquids have a 1:1 ratio in metric—1 liter of water weighs exactly 1 kilogram. It’s beautiful. It’s simple.

Second, if you’re working with tools or engines, buy the measuring cup that matches the manual. Don't use a US quart jar to measure out 4 liters of hydraulic fluid. You'll be short by 214ml, and your equipment will groan.

Third, remember the "5% Rule." If you absolutely have to substitute, remember that the liter is the "big brother." You need slightly more quart-units to fill a liter-space, and you'll have leftover liquid if you try to pour a liter into a quart jar.

Actionable Next Steps

Instead of trying to memorize complex decimal points, change your workflow.

- Buy a dual-measurement pitcher. Most modern Pyrex or plastic measuring cups have liters on one side and quarts/cups on the other. Use the side that matches your instructions. Do not convert in your head.

- Check your labels. Look at the fine print on the back of the bottle. Most products sold in the US now list both (e.g., 32 FL OZ / 946 mL). Use the mL number for accuracy.

- Verify the region. If the keyword is "quart," make sure it's not an "Imperial Quart" if the author is from the UK, Canada, or Australia.

- Scale up carefully. The error margin of 5% isn't bad for one cup, but at 4 quarts, it's a massive discrepancy. Always multiply your error by the total volume to see if you can live with the results.

The reality is that 4 quarts in a liter is a physical impossibility. You're trying to fit about 128 ounces of liquid into a 33.8-ounce container. It’s better to think of them as two different languages. You can translate between them, but you can't just pretend they're the same word. If you're precision-filling a radiator or baking a soufflé, take the extra ten seconds to use the right measuring tool. Your engine—and your dinner guests—will thank you.