You’re standing at a checkout counter, or maybe you're just daydreaming about what it would feel like to hold a single piece of paper worth a month's rent. It’s a classic question that pops up in trivia nights and banking lobbies alike: is there a $1,000 dollar bill?

The short answer is yes. It exists. But if you're expecting to withdraw one from a Chase ATM or get one back as change at Target, you're out of luck.

High-denomination currency feels like a myth from a Gatsby-era fever dream. We are so used to the "Benjamins" being the ceiling of American cash that anything higher feels fake, like Monopoly money or those annoying "Million Dollar" gospel tracts people leave on bus seats. Yet, the United States government did, in fact, print $1,000 bills for decades. They were real, they were legal tender, and technically, they still are. If you found one tucked inside an old piano from your great-grandmother’s estate, you could take it to a grocery store and buy a very expensive steak.

🔗 Read more: AMD Share Price Today: What Most People Get Wrong About the 2026 AI Boom

Please don't do that, though. You'd be losing a fortune.

The weird history of the grand

The most famous version of this bill features Alexander Hamilton—who currently lives on the $10—but the one most collectors hunt for is the 1928 or 1934 Series featuring Grover Cleveland. It’s a bit ironic. Cleveland is the only president to serve two non-consecutive terms, and he ended up on a bill that almost nobody has ever seen in person.

Why did we even make them?

Back in the day, before wires, digital transfers, and encrypted apps, moving large sums of money was a logistical nightmare. If a bank needed to settle a massive debt with another bank, they didn't want to show up with crates of $1 bills. It was dangerous and heavy. These high-value notes were basically the "wire transfers" of the early 20th century. They allowed for the physical movement of wealth between financial institutions without needing a literal horse and carriage to haul the weight.

By 1945, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing stopped churning them out. They just weren't being used by the general public. Inflation hadn't yet turned a thousand dollars into "car repair money"; back then, a thousand dollars was "buy a house" money. Most people lived their entire lives without ever seeing a $50 bill, let alone a note with three zeros after the one.

Why the government killed the high-value note

If you're wondering why we don't bring them back—especially since inflation makes $100 feel like a $20 used to—look no further than the war on crime.

In 1969, the Department of the Treasury and the Federal Reserve officially began retiring high-denomination notes. They didn't just stop printing them; they started actively destroying them. The reason was simple: organized crime.

Imagine you’re a drug kingpin or a money launderer in the late 60s. Carrying $1 million in $20 bills requires several heavy suitcases. It’s conspicuous. It’s clumsy. But $1 million in $1,000 bills? That fits in a slim briefcase. Or a large coat pocket. By eliminating the big bills, the government made it significantly harder for criminals to move massive amounts of untraceable cash across borders or between hideouts.

Even today, there is a recurring debate among economists about whether we should kill the $100 bill for the same reason. Former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers has argued that getting rid of the $100 would help curb tax evasion and illegal activity. If the government is looking at the $100 with a side-eye, they definitely aren't bringing back the $1,000.

What happens if you find one?

This is where things get interesting for the average person.

If you walk into a bank with a 1934 Grover Cleveland $1,000 bill, the teller is legally obligated to credit your account for $1,000. But if you do that, you are essentially throwing away thousands of dollars.

Because these bills are no longer in circulation, they have become "numismatic" items. That’s just a fancy word for collectibles. Depending on the condition, the series, and the "seal" color, a $1,000 bill can be worth anywhere from **$2,000 to $5,000** on the open market. Some rare versions in "Gem Uncirculated" condition have even fetched north of $10,000 at auction.

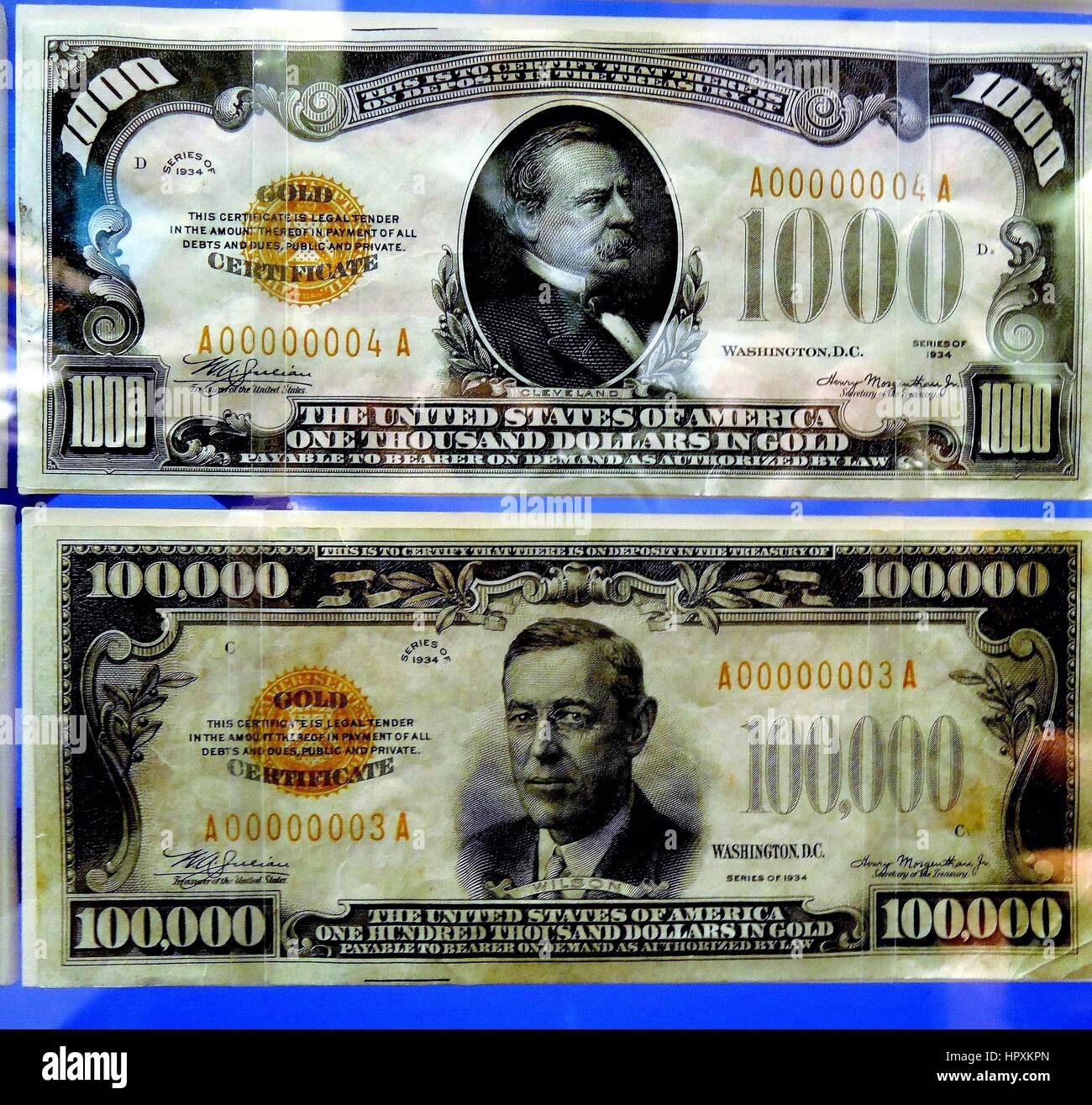

There are also the "Gold Certificates." These were printed in 1928 and featured bright orange backs. They are stunning. They are also incredibly rare because, for a while, it was actually illegal for private citizens to own them after the government went off the gold standard. Today, they are legal to own, and if you have a high-grade $1,000 Gold Certificate, you’re looking at a serious payday that dwarfs the face value of the note.

💡 You might also like: American Tower Corporation Stock: What Most People Get Wrong About 5G REITs

The $10,000 and $100,000 outliers

If you think the $1,000 bill is wild, it goes deeper. The U.S. also printed $5,000 and $10,000 bills. The $10,000 bill featured Salmon P. Chase.

Who?

Exactly. Chase was the Treasury Secretary under Lincoln, and he basically put his own face on the money to boost his political profile. It didn't work for his presidential ambitions, but it did immortalize him on the highest-denomination bill ever made available to the public.

Then there’s the white whale: the $100,000 bill.

This note featured Woodrow Wilson. It was never released to the public. It was a "Gold Certificate" used only for transactions between Federal Reserve banks. If you are ever caught holding one of these, you're either a museum curator or you’ve committed a very high-level federal crime. It is illegal for a private collector to own one. They are strictly government property.

Practical advice for the curious

Maybe you’re looking to buy one as an investment. Or maybe you’re just checking your attic. Either way, here is the reality of the situation.

First, watch out for fakes. High-denomination bills are a magnet for counterfeiters. Real bills from the 1920s and 30s were printed on high-quality linen paper with distinct red and blue security fibers. If it feels like standard printer paper or if the "ink" looks like it was sprayed on by an inkjet, it's a prop.

Second, if you do find one, do not clean it.

🔗 Read more: 1 billion won in US dollars: Is it actually as much as it sounds?

Newbie collectors often think they can increase the value by "washing" the bill or ironing out the creases. This is a disaster. Collectors want "originality." Any chemical cleaning or physical alteration will tank the value by 50% or more. Keep it in a PVC-free plastic sleeve and take it to a reputable coin and currency dealer.

Third, check the seal. Most $1,000 bills you'll see have a green seal (Federal Reserve Note). If you find one with a blue seal, a red seal, or an orange seal, you've moved from "cool find" to "serious money" territory.

Why we won't see them again

We live in a digital world now. Honestly, physical cash is becoming a niche product for small daily transactions. With the rise of FedNow, Venmo, and various cryptocurrencies, the need for a physical $1,000 bill has vanished.

If you need to move a million dollars today, you click a button. You don't need a briefcase full of Grover Clevelands.

Besides, the logistical headache for a business to accept a $1,000 bill would be insane. Can you imagine the poor teenager at a fast-food joint trying to verify if a $1,000 bill is real? They can barely get change for a $50 half the time. The security risk alone for a small business to keep that kind of cash in a drawer would make it a liability, not an asset.

So, while the answer to is there a $1,000 dollar bill is a resounding "yes," it remains a relic of a different era. It represents a time when money was heavy, banks were physical fortresses, and the "grand" was an almost mythical amount of wealth.

Actionable steps if you want to own one

- Visit a Currency Show: Don't buy your first high-denomination bill on eBay from a seller with no history. Go to a Professional Currency Dealers Association (PCDA) show where you can see the bills in person.

- Look for Grading: Only buy bills that have been "slabbed" or graded by third-party services like PMG (Paper Money Guaranty) or PCGS. This ensures the bill is authentic and accurately describes its condition.

- Start Small: If you just want the "vibe" of high-value currency without the $3,000 price tag, look for "fractional currency" or "obsolete notes" from the 1800s. They are beautiful, historic, and much more affordable.

- Verify the Serial Number: If you are offered a $1,000 bill with a serial number like 00000001 or 12345678, be extremely skeptical. Those are the most faked numbers in the world.

- Check Museum Collections: If you just want to see one, the Smithsonian in D.C. or the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago's Money Museum have incredible displays where you can see the $10,000 and $100,000 notes up close.