It wasn't a sleek, fast warship. Honestly, the James Cook ship Endeavour was a bit of a tub. Before it became a legend of maritime exploration, it spent its days hauling coal around the freezing waters of the North Sea under the name Earl of Pembroke. It was chunky. It was slow. But it was incredibly tough.

That’s basically why the British Admiralty chose it. When you’re heading into the complete unknown, you don't need speed. You need a flat-bottomed boat that can be beached for repairs and has enough room in the hold for thousands of pounds of salt beef and "portable soup."

Why the James Cook Ship Endeavour Wasn't What You Think

If you imagine a grand vessel with towering masts and golden trim, you’re thinking of the wrong boat. The Endeavour was a bark—a workhorse. When James Cook set sail from Plymouth in 1768, he wasn't just on a mission to find "the great southern continent." He was also a science nerd on a government-funded field trip.

The ship carried 94 people. Imagine that. Nearly a hundred men crammed into a vessel only 100 feet long. It was tight. It smelled like damp wool, livestock, and unwashed sailors. Joseph Banks, the wealthy botanist on board, brought along a literal entourage, including two artists and two Black servants, Thomas Richmond and George Dorlton. They were all vying for space with barrels of sauerkraut.

Wait, sauerkraut? Yeah. Cook was obsessed with it. He famously used it to prevent scurvy, a gruesome disease that turned sailors' gums to mush and opened up old wounds. Most captains lost half their crew to scurvy. Cook lost zero to the disease on this voyage. He basically forced the men to eat fermented cabbage by making the officers eat it first to make it look like a "luxury" item. It worked.

The Secret Mission Hidden in the Pocket

Publicly, the James Cook ship Endeavour was headed to Tahiti to observe the Transit of Venus. Scientists wanted to calculate the distance from the Earth to the Sun. It was a big deal for the Royal Society. But Cook had secret orders from the Admiralty tucked away in a sealed envelope.

Once the stars were tracked, he was told to open it.

The orders were clear: go south. Go west. Find the continent that everyone assumed was there to "balance" the globe. He didn't find Antarctica, but he did stumble upon the east coast of Australia and mapped New Zealand with terrifying accuracy. If you look at his 18th-century charts today, they are surprisingly close to modern GPS readings. The man was a mapping machine.

Near Disaster at the Great Barrier Reef

In June 1770, the voyage almost ended in a watery grave. The Endeavour was sailing through what we now know as the Great Barrier Reef. Suddenly, a sickening crunch. The ship was stuck on coral.

It was a nightmare.

📖 Related: Le Dokhan's a Tribute Portfolio Hotel Paris: What Most People Get Wrong

Water started pouring in. The crew spent twenty-four hours pumping like mad. They threw everything overboard to lighten the load—cannons, decayed stores, stone ballast. They even "fothered" the ship, which is a fancy old-school term for sewing oakum and wool into a sail and dragging it under the hull so the suction would pull it into the hole. It worked well enough to get them to the shore of what is now Cooktown.

They spent seven weeks repairing the hull. During this time, they saw "kanguru." Banks and his team were losing their minds over the flora and fauna. To the local Guugu Yimithirr people, these strange white men were likely a confusing, smelly apparition. The interactions were tense but, at that specific moment, mostly peaceful. That wouldn't always be the case as the years rolled on.

The Life of a Sailor on the Endeavour

Life was monotonous until it was terrifying. You ate hardtack biscuits that were often infested with weevils. You slept in a hammock that swung with the roll of the ship.

Cook was a strict disciplinarian, but he was also weirdly progressive about health. He demanded the decks be scrubbed with vinegar and smoked with sulfur to kill "miasmas." He was a son of a farm laborer who rose through the ranks because he was just that good at math and navigation. He wasn't an aristocrat. He was a professional.

💡 You might also like: Studio 6 West Palm Beach: What Most People Get Wrong

What Happened to the Ship?

The end of the James Cook ship Endeavour is actually kinda depressing. After returning to England in 1771, it didn't get a museum spot. It was sold back into the merchant trade. It was renamed the Lord Sandwich II and ended up being used as a troop transport during the American Revolutionary War.

In 1778, the British scuttled it—intentionally sank it—in Newport Harbor, Rhode Island. They did it to create a blockade against the French fleet. For centuries, it sat in the muck.

Archaeologists from the Australian National Maritime Museum and the Rhode Island Marine Archaeology Project have spent years diving on those wrecks. In 2022, Australian researchers claimed they’d positively identified the wreck of the Endeavour. The Americans were a bit more cautious, saying it’s "likely" but not 100% proven. Either way, the physical remains are mostly splinters and memories eaten by shipworms.

The Legacy is Complicated

We can't talk about the Endeavour without acknowledging the impact. For Europeans, it was an age of discovery. For the Indigenous peoples of Australia and the Pacific, it was the beginning of an era of dispossession and disease.

Historians like Maria Nugent have explored how these encounters are remembered. It wasn't just a ship; it was a floating laboratory and a precursor to colonization. When you look at the Endeavour today, you have to see both things at once: the incredible feat of seamanship and the painful history that followed its wake.

How to See the Endeavour Today

You can’t see the original (unless you’re a diver with a permit in Rhode Island), but you can see the next best thing.

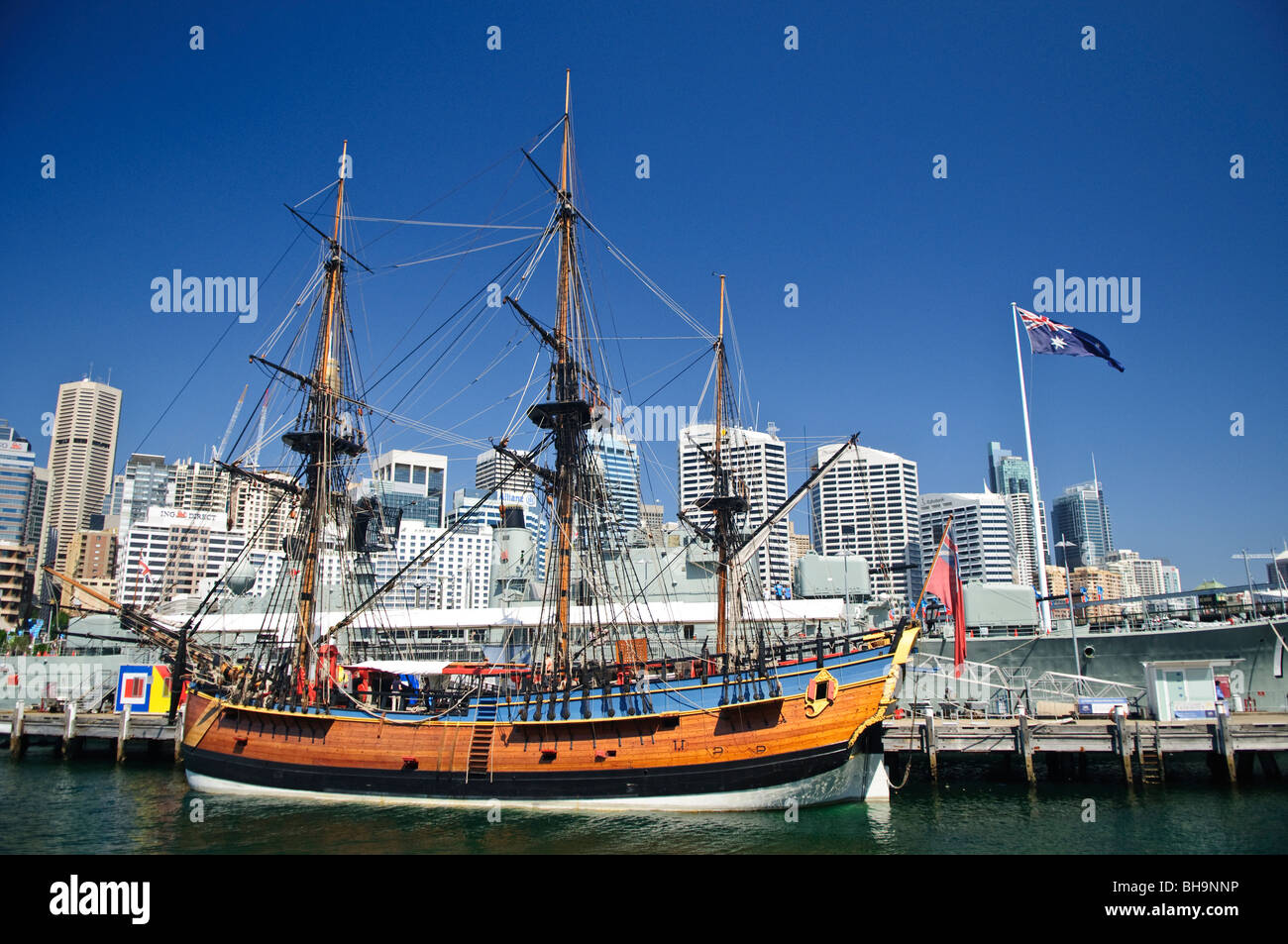

- The Replica in Sydney: The Australian National Maritime Museum has a stunning, full-scale replica. They actually sail it. If you ever get a chance to stand on the deck, do it. You’ll realize how small the ship actually was compared to the vastness of the Pacific.

- Whitby, England: This is where the ship was built. The Captain Cook Memorial Museum is housed in the house where Cook lived as an apprentice. It’s atmospheric and gives you a real sense of the coal-trade roots of the vessel.

- The British Library: They hold many of Cook’s original journals and the charts he drew on the Endeavour. Seeing his handwriting—precise and steady—brings the whole thing home.

Understanding the Marine Tech of 1768

The Endeavour used a steering wheel, which was still relatively new tech compared to the old tiller bars. It had three masts and a suite of square sails.

Navigation was done via a sextant and a quadrant. The big challenge back then was longitude. How do you know how far east or west you are? Cook used the "lunar distance" method, which involved incredibly complex math and staring at the moon for hours. He also had a copy of the Nautical Almanac. It was tedious, slow work, but he was one of the few people alive who could do it accurately.

🔗 Read more: Why Everyone Is Obsessed With Vandyke Bed and Beverage Right Now

Actionable Steps for History Enthusiasts

If you want to go beyond the surface of the James Cook ship Endeavour, don't just read a Wikipedia summary.

- Read the Journals: The digitized versions of Cook's and Joseph Banks' journals are available online through the National Library of Australia. They are surprisingly readable. You’ll find entries about the "prodigious number of birds" and the sheer frustration of being stuck on the reef.

- Trace the Route on Google Earth: Follow the coastline of New Zealand and the East Coast of Australia. When you see the jagged edges of the Great Barrier Reef from a satellite view, you’ll understand why the crew was terrified.

- Visit Newport Harbor: If you're in the U.S., the Newport area has several markers and museum exhibits dedicated to the "transport" ships sunk in 1778. It’s a haunting connection to a ship that saw the other side of the world.

- Explore Indigenous Perspectives: Look into the "Eight Days in May" project or the works of Indigenous historians who detail the Gweagal people's first contact with the Endeavour at Botany Bay. It provides a necessary counter-narrative to the "discovery" myth.

The Endeavour wasn't just wood and sail. It was a catalyst. Whether you view it as a triumph of science or a harbinger of change, its impact on the modern map is undeniable.